This Court Case Could Make It a Crime To Be a Journalist in Texas

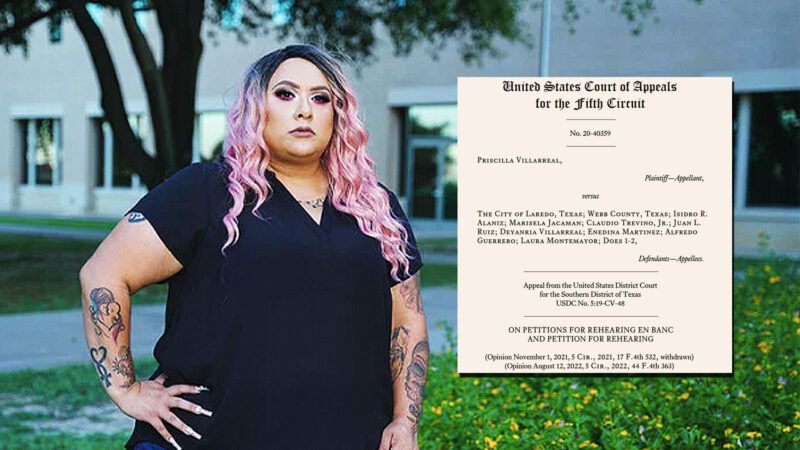

Priscilla Villarreal found herself in a jail cell for publishing two routine stories. A federal court still can't decide what to do about that.

It has been five years since police in Laredo, Texas, mocked and jeered at Priscilla Villarreal, a local journalist often critical of cops, as she stood in the Webb County Jail while they booked her on felony charges. Her crime: asking the government questions.

That may seem like a relatively obvious violation of the First Amendment. Yet perhaps more fraught is that, after all this time, the federal courts have still not been able to reach a consensus on that question. Over the years, judges in the 5th Circuit have ping-ponged back and forth over whether jailing a journalist for doing journalism does, in fact, plainly infringe on her free speech rights.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas awarded those officers qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that allows state and local government officials to violate your constitutional rights without having to face federal civil suits if that violation has not been "clearly established" in case law. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit forcefully overturned that: "If [this] is not an obvious violation of the Constitution, it's hard to imagine what would be," wrote Judge James C. Ho.

Last week, the full spate of judges on the 5th Circuit voted to rehear the case in a rare move that signals some discontent with Ho's majority conclusion. Put differently, it's not looking good for Villarreal, nor for any journalist in the 5th Circuit who would like to do their job without fear of going to jail for it.

In April 2017, Villarreal, who reports near the U.S.-Mexico border, broke a story about a Border Patrol agent who committed suicide. A month later, she released the surname of a family involved in a fatal car accident. The agency that confirmed both pieces of information: the Laredo Police Department. The agency that would bring felony charges against her six months later for those acts of journalism: the Laredo Police Department.

At the core of Villarreal's misfortune is a Texas law that allows the state to prosecute someone who obtains nonpublic information from a government official if he or she does so "with intent to obtain a benefit." Villarreal operates her popular news-sharing operation on Facebook, where her page, Lagordiloca News, has amassed 200,000 followers as of this writing.

So to jail Villarreal, police alleged that she ran afoul of that law when she retrieved information from Laredo Police Department Officer Barbara Goodman and proceeded to publish those two aforementioned stories, because she potentially benefited by gaining more Facebook followers. Missing from that analysis is that every journalist, reporter, or media pundit has an "intent to benefit" when she or he publishes a story, whether it is to attract viewers, readers, or subscribers. Soliciting information from government officials—who, as Villarreal's case exemplifies, sometimes feed reporters information—is called a "scoop," and it's not new.

Yet it was an argument that, in some sense, resonated with Judge Priscilla Richman, the chief jurist on the 5th Circuit, who almost certainly voted in favor of reconsidering the court's ruling. "In fact, Villareal's [sic] Complaint says that she 'sometimes enjoys a free meal from appreciative readers, . . . occasionally receives fees for promoting a local business [and] has used her Facebook page [where all of her reporting is published] to ask for donations for new equipment necessary to continue her citizen journalism efforts," she wrote in August, rebuking Ho's conclusion. "With great respect, the majority opinion is off base in holding that no reasonably competent officer could objectively have thought that Villareal [sic] obtained information from her back-door source within the Laredo Police Department with an 'intent to benefit.'"

Such an interpretation would render the media industry an illegal operation, and everyone who participates—whether they be conservative, liberal, far-left, far-right, or anything in-between—criminals. "Other journalists are paid full salaries by their media outlets," writes Ho. Can confirm. Is that somehow less consequential than receiving free lunch or getting a new spike of followers on a social media platform (which is something that many journalists employed full time also set out to do)? "In sum, it is a crime to be a journalist in Texas, thanks to the dissent's reading of § 39.06(c)," Ho adds.

Debates around free speech are often polarized along predictable partisan lines. More specifically, they're often polarized by the content espoused. It's an easy task to support the idea of free speech when you enjoy what's being said. But the First Amendment does not pertain solely to popular speech, which, by nature of common sense, needs considerably less protection than the content deemed unpopular by the majority.

"It's not about just one person, it's not about just one case," says J.T. Morris, a senior attorney at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), which is representing Villarreal. "It's about the First Amendment rights of all citizens to ask their public officials questions."

This appears to be something Judge Ho understands. Appointed by President Donald Trump, he has drawn headlines in recent weeks for his critiques of cancel culture at Yale Law School, where left-leaning students have developed a reputation for petulantly shouting down those with differing views. In our current partisan landscape, then, Villarreal might seem like an odd character for Ho to sympathize with; it's safe to say she would more likely qualify as a left-leaning hero than a right-leaning one. The journalist doggedly covers law enforcement with profanity-laced commentary: She once published a video of an officer choking someone at a traffic stop, and railed at a district attorney who dropped criminal charges against someone for animal abuse—a pattern which perhaps explains why police were eager to use the force of the law against her, the first time they ever invoked the statute in question.

But to make an about-face based on the content fundamentally confuses the meaning of free speech. Put differently, if you're upset that some students at Yale Law School are not mature enough to engage with those who think differently, or that social media vigilantes unfairly derail careers for WrongThink, then so too should you care that a woman in small-town Texas spent time in jail for promoting a message that might make you uncomfortable.

It's a problem of principle, and it's one that may also pervade the judiciary. "It should go without saying that forcing a public school student to embrace a particular political view serves no legitimate pedagogical function and is forbidden by the First Amendment," Ho wrote in Oliver v. Arnold last year. The case, which went under the radar, pertained to a conservative teacher who discriminated against a liberal student, temporarily turning the discussion on bias in education on its head. That student, Mari Leigh Oliver, won—by the skin of her teeth. Seven judges wanted to rehear the case, suggesting they disagreed with the ruling, while the remaining 10 declined.

Addressing some of the judges who would side against Oliver, Ho wrote that "it's unclear why they think [other] claims should succeed, and only Oliver's should lose." After all, the roles are typically reversed; conservatives are frequently the ones outweighed in academic settings. But if you only apply your principles when they suit you—if you only stand against the illiberal Yale students and not for the Villarreals or the Olivers—then you are sure to eventually find yourself on the losing end. And then what?

Show Comments (136)