Trump's Anti-Crime Agenda Contradicts His Criticism of Biden's Legislative Record

Since he favors aggressive drug law enforcement, severe penalties, and impunity for abusive police officers, he may have trouble persuading black voters that he is on their side.

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Donald Trump attacked Joe Biden from the left on drug policy and criminal justice, slamming him for pushing harsh laws that had disproportionately hurt black people. Trump is trying that same tack again this time around, portraying Biden as a racist eager to lock up African Americans. "We must not forget that it was Joe Biden who was a key figure in passing the 1994 Crime Bill, which disproportionately harmed Black communities through harsh sentencing laws and increased incarceration rates," Janiyah Thomas, the Trump campaign's "black media director," said in an emailed press release on Thursday.

That stance is consistent with aspects of Trump's record as president, including his support for the FIRST STEP Act, a package of sentencing and prison reforms that he signed into law in December 2018. But it is blatantly inconsistent with Trump's current drug policy and criminal justice agenda, which favors aggressive enforcement, severe penalties, and impunity for abusive police officers.

Like Biden, who in 2022 promised to "beat the opioid epidemic" by "stop[ping] the flow of illicit drugs," Trump indulges in the familiar fantasy that interdiction can prevent Americans from consuming politically disfavored intoxicants. But Trump goes bigger, imagining "a full naval embargo on the drug cartels" and deployment of "military assets" to "inflict maximum damage" on them. If the U.S. does not get "the full cooperation of other governments to stop this menace," he warns, "we will expose every bribe, every kickback, every payoff, and every bit of corruption that is allowing the cartels to preserve their brutal reign."

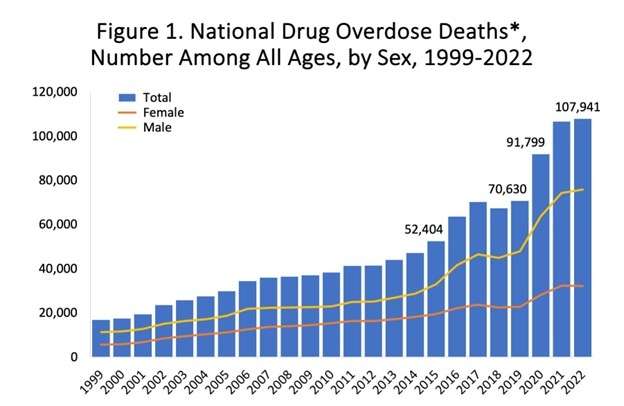

Trump's insistence that he is a tougher drug warrior than Biden is hard to reconcile with his portrayal of Biden as an overzealous drug warrior who was heedless of the damage his legislation did. And Trump does not offer much evidence from his own record as president that determination and violence can defeat the economics of prohibition. "For three decades before my election," he says, "drug overdose deaths increased every single year. We took the drug and fentanyl crisis head on, and we achieved the first reduction in overdose deaths in more than 30 years."

Trump is referring to a slight decrease in drug-related deaths between 2017 and 2018. He neglects to mention that the number went back up again in 2019 and 2020, reaching record levels during his administration—a trend that continued after he left office. Contrary to Trump's spin, the 1.7 percent drop in opioid-related deaths he highlights does not suggest his ideas for "Ending the Scourge of Drug Addiction in America" are any better than Biden's.

In addition to deploying America's military might against drug cartels, Trump promises to "take down the gangs" that "distribute these deadly narcotics on a local level." That will entail a lot of arrests and a lot of prison sentences, producing the "increased incarceration rates" that Trump decries. Just as the policies that Biden supported as a senator "disproportionately harmed Black communities," so will the crackdown that Trump has in mind.

Trump says he also will "ask Congress to ensure that drug dealers, kingpins and human traffickers receive the death penalty." Executing drug dealers is not a new idea for Trump, who has repeatedly recommended that policy over the years. But it is inconsistent with with his criticism of Biden's legislative record, his condemnation of "very unfair" drug penalties, his commutations for nonviolent drug offenders who had received those penalties, and his support for sentencing reform.

The most famous beneficiary of Trump's clemency was Alice Johnson, a first-time offender who had received a life sentence for participating in a Memphis cocaine trafficking operation. "You have many people like Mrs. Johnson," Trump told Fox News in 2018. "There are people in jail for really long terms." Trump highlighted Johnson's case during his 2019 State of the Union address, in a 2020 Super Bowl ad, and at the 2020 Republican National Convention, where Johnson gave a grateful speech.

As a black woman hit with a draconian sentence under inflexible drug laws, Johnson was a useful exhibit in Trump's case that African-American voters should be grateful to him and wary of Biden. But after Trump re-upped his death penalty proposal in a 2023 interview with Fox News, his mercy collided with his blood lust.

When Bret Baier pointed out that someone like Johnson would have been "killed under your plan," Trump was flummoxed. "No, no, no," he said. "It would depend on the severity," he added. He also noted that the death penalty he imagined would not apply retroactively to Johnson herself and suggested that, had it been the law at the time, it would have deterred her from getting involved in drug dealing.

By that point, Trump had become disenchanted with sentencing reform. In a 2022 interview with New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman, he bitterly complained that he had not reaped the political reward he expected from backing the FIRST STEP Act. "Did it for African Americans," he told her. "Nobody else could have gotten it done. Got zero credit."

Despite that disappointing experience, Trump is trying again, and his drug war enthusiasm is not the only reason to be skeptical of his pitch. His anti-crime agenda, which reflects his authoritarian instincts, includes a promise to "strengthen qualified immunity and other protections for police officers."

As critics across the political spectrum have been pointing out for years, the doctrine of qualified immunity, which bars federal civil rights claims unless they allege violations of "clearly established" law, often shields police officers (and other government officials) from liability for outrageous misconduct. But as Trump sees it, that shield is not big and strong enough.

Trump has promised to "indemnify" cops "against any and all liability." He apparently does not realize that police officers already are routinely indemnified in the rare cases when they are held liable for abuse, and he implausibly argues that the threat of liability has a paralyzing impact, discouraging cops from doing their jobs. In case beefing up qualified immunity does not do the trick, Trump also promises to give police "immunity from prosecution" for violating people's rights.

Trump thinks total impunity for abusive cops is necessary to "reclaim safety, dignity, and peace for law-abiding Americans." In his view, remedies for police abuse, such as insisting that officers obey the Constitution or authorizing criminal charges and civil rights lawsuits when they don't, are dangerous to public order. He believes police officers should not have to worry that they could face charges or litigation simply because they broke the law, and maybe a few heads, while doing their jobs.

Given that position, Trump may have a hard time persuading black voters that he is on their side. As Reason's Billy Binion notes, survey data suggest those voters want the law and order that Trump promises, but not at the cost of giving free rein to armed agents of the state.

Trump's positions on drug policy and criminal justice are utterly incoherent. Mass incarceration is bad, he says, even as he recommends policies that would imprison more people for conduct that violates no one's rights. Drug laws that disproportionately hurt African Americans are troubling, he thinks, but they should be enforced more aggressively. A life sentence for Alice Johnson was plainly unjust, he says, but a death sentence would have been appropriate. Biden was mindlessly punitive, he argues, but Trump is preferable because he is even tougher. Trump cannot logically have it both ways, but that will not stop him from trying.

Show Comments (131)