The Justice Department Quietly Ends Reprosecution of Man Who Received Clemency From Trump

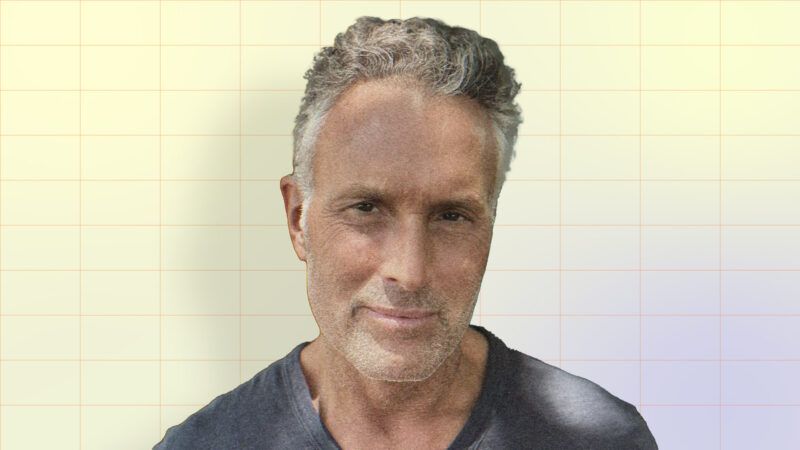

Philip Esformes was sentenced for charges on which a jury hung. After receiving a commutation, the federal government vowed to try to put him back in prison.

A Florida man accused of facilitating an illegal health care scheme has been spared additional prison time, ending the Justice Department's attempt to reprosecute him after his sentence was commuted by former President Donald Trump.

Philip Esformes on Thursday pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud and was sentenced to time served, with prosecutors agreeing to dismiss the remaining five counts. It's a quiet conclusion to a controversial prosecution that saw the federal government resuscitate the criminal case against him not long after he'd spent four and a half years behind bars and was released from prison in December 2020, despite that he had already been sentenced for the same counts on which they sought to retry him.

In 2016, Esformes—who owned a network of skilled nursing and assisted living facilities—was arrested, held without bond in solitary confinement, and charged with over two dozen counts in connection with allegedly bribing doctors to secure patients for his establishments, where the government says he billed Medicare and Medicaid for unnecessary treatments. But while Esformes was convicted on 20 of those counts, including money laundering, the jury deadlocked on six of the most serious charges.

A judge sentenced him, however, as if he'd been convicted of them, in a little-known practice that often offends people's basic impressions of the protections built into the U.S. criminal justice system. Particularly in federal court, if a defendant receives a split verdict—a conviction on one or some counts, with an acquittal or a hung jury on the remaining charges—a judge may punish them as if they were found guilty of everything.

Esformes' case was somewhat timely in that "acquitted conduct sentencing," as it's typically called, has come under particular scrutiny in recent years. The Supreme Court has previously ruled that judges are permitted to consider counts on which a jury rendered a not guilty verdict, or by extension on which they deadlocked, if he or she decides by a "preponderance of the evidence" that the defendant is, in fact, guilty. That standard of proof is considerably lower than the one employed by juries, which are instructed to convict only if the panel concludes the defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Judge Robert Scola of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida was explicit that Esformes' 20-year sentence was in part based on the charges for which a jury did not reach a verdict. (Esformes was also ordered to forfeit $38.7 million and to pay $5.5 million in restitution, which were not absolved with the clemency order handed down by Trump.) "I don't know what more you are going to get out of the case if you try those additional counts," he told the prosecution at a restitution hearing in November 2019. There was no utility in a retrial, Scola said, because he had already baked the charges on which a jury hung into the prison sentence he'd given Esformes two months prior.

The federal government agreed. "Certainly, Your Honor, if the case comes back on appeal, we would ask the hung counts to run with the appeal so the whole thing could be retried," Assistant U.S. Attorney Elizabeth Young responded. "We have entered into agreements to dismiss the hung counts if the defendant's appeal is dismissed, and we would agree to do so here."

But after Esformes received clemency in December 2020, the Justice Department reneged on its promise, pledging to retry Esformes on an indictment that isolated the hung counts for which he'd already been sentenced and received a commutation.

The move was not without criticism. "This defendant, as much as you might not like him…do you think he should be punished two or three times for the same conduct?" Brett Tolman, the former U.S. Attorney for the District of Utah and now the executive director of Right on Crime, asked me last year. "I don't find anybody who thinks that's fair." Both Sen. Mike Lee (R–Utah) and Rep. Andy Biggs (R–Ariz.) sent letters urging Attorney General Merrick Garland to change course, accusing his department of politicizing the clemency process. The Subcommittee on Crime and Federal Government Surveillance called a congressional hearing centered around Esformes' case in June 2023, during which both sides of the political aisle sparred over a "two-tiered system of justice."

The reaction, however, did not fall entirely neatly along partisan lines. "If you walk through the facts, it's clearly double jeopardy," Jessica Jackson, the left-leaning attorney and activist who helped spearhead the advocacy around the landmark FIRST STEP Act, told Reason last year. "The judge on the record at sentencing used the hung conduct as part of his sentence….That sentence was then commuted by President Trump. In my mind, while it's a novel area of legal precedent, this is double jeopardy by the letter of the law, really."

The root of the legal issue here—whether or not judges should be able to sentence defendants for crimes they weren't convicted of—continues to be a subject of intense debate, the climax of which coincided with Esformes' reprosecution. In June of last year, just over a week after the congressional hearing dedicated to his case, the Supreme Court declined to hear a petition from Dayonta McClinton, who was sentenced to 19 years in prison after he helped rob a CVS Pharmacy. "The driving force" of that sentence, the judge said, was for killing his friend, Malik Perry, after a jury acquitted McClinton of causing that very death.

Show Comments (44)