A Ruling Against a Man Arrested for a COVID-19 Joke Highlights the Influence of a Pernicious Analogy

A federal judge compared Waylon Bailey’s Facebook jest to "falsely shouting fire in a theatre."

Back in March 2020, a dozen or so sheriff's deputies wearing bullet-proof vests descended upon Waylon Bailey's home in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, with their guns drawn, ordered him onto his knees with his hands on his head, and arrested him for a felony punishable by up to 15 years in prison. The SWAT-style raid was provoked by a Facebook post in which Bailey had made a zombie-themed joke about COVID-19.

Although a federal appeals court recently ruled that Bailey could pursue civil rights claims based on that incident, a judge initially blocked his lawsuit, saying his joke created a "clear and present danger" similar to the threat posed by "falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing panic." That decision illustrates the continuing influence of a misbegotten, century-old analogy that is frequently used as an excuse to punish or censor constitutionally protected speech.

Bailey's joke alluded to the 2013 zombie movie World War Z, starring Brad Pitt. Bailey jested that the Rapides Parish Sheriff's Office (RPSO) had told deputies to shoot "the infected" on sight, adding: "Lord have mercy on us all. #Covid9teen #weneedyoubradpitt."

RPSO Detective Randell Iles, who was immediately assigned to investigate the post, claimed it violated a state law against "terrorizing" the public. But as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit noted last Friday, Bailey's conduct clearly did not fit the elements of that crime, which explains why prosecutors dropped the charge after local press reports tarred Bailey as a terrorist.

The 5th Circuit overturned a July 2022 decision in which U.S. District Judge David C. Joseph dismissed Bailey's claims against Iles and Sheriff Mark Wood. Joseph, who thought Iles had probable cause to arrest Bailey, said "publishing misinformation during the very early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and [a] time of national crisis was remarkably similar in nature to falsely shouting fire in a crowded theatre."

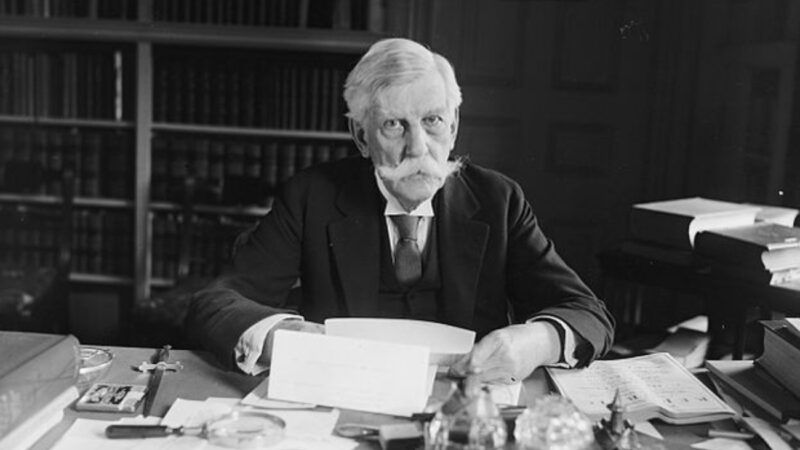

That was a reference to Schenck v. United States, a 1919 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the Espionage Act convictions of two socialists who had distributed anti-draft leaflets during World War I. Writing for the Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. said "the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic."

In the 1969 case Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Court modified the "clear and present danger" test it had applied in Schenck—a point that Joseph somehow overlooked. Under Brandenburg, even advocacy of criminal conduct is constitutionally protected unless it is "directed" at inciting "imminent lawless action" and "likely" to do so—an exception to the First Amendment that plainly did not cover Bailey's joke.

Although Schenck is no longer good law, Holmes' passing comment about shouting fire lives on in judicial decisions and in popular discourse. After last year's racist mass shooting in Buffalo, for example, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul invoked the analogy as a justification for censoring online "hate speech," which she erroneously claimed is not protected by the First Amendment.

Even Justice Samuel Alito has cited "shouting fire in a crowded theater" as a well-established exception to the First Amendment. Yet Holmes' description of that scenario, which had nothing to do with the facts of the case, did not establish any such principle.

Alito presumably had in mind a situation like the sort covered by Louisiana's "terrorizing" statute, which among other things makes it a crime to intentionally cause "evacuation of a building" by falsely reporting "a circumstance dangerous to human life." But as Hochul and like-minded advocates of speech restrictions see it, the analogy extends much further.

"Anyone who says 'you can't shout fire in a crowded theater' is showing that they don't know much about the principles of free speech," Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, observed in 2021. "This old canard, a favorite reference of censorship apologists, needs to be retired."

© Copyright 2023 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (11)