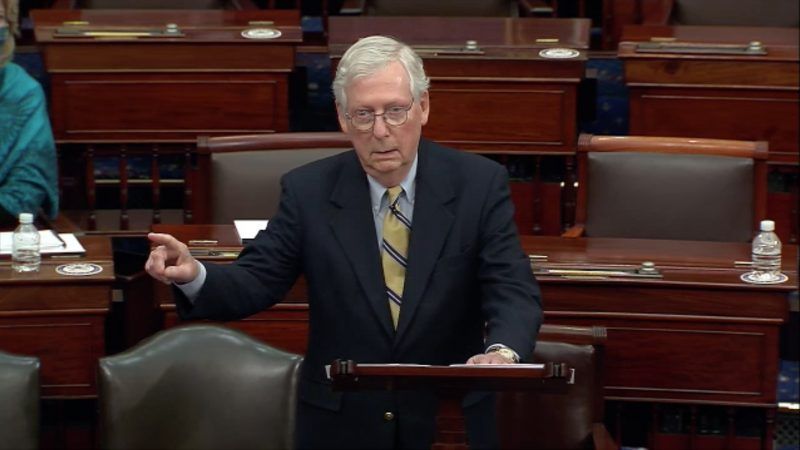

After Voting to Acquit Trump, Mitch McConnell Explains Why He Was Guilty

The Senate minority leader's triangulation does not bode well for the GOP's ability to stand for something other than a personality cult.

After he voted to acquit Donald Trump of inciting the Capitol riot, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R–Ky.) explained why the former president was guilty. McConnell explained the apparent contradiction by arguing that the Senate does not have the authority to try a former president. But as he conceded, that is "a very close question," and McConnell's rationale for his vote is puzzling in light of what he did after the House voted to impeach Trump a month ago. McConnell's mixed message reflects the predicament of a party that has built its identity around a reckless, unprincipled demagogue whose influence will continue to weigh down Republicans for years to come.

"Former President Trump's actions preceding the riot were a disgraceful dereliction of duty," McConnell said in a Senate floor speech on Saturday after seven of his fellow Republicans joined 50 Democrats in voting to convict. "There is no question that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of that day. The people who stormed this building believed they were acting on the wishes and instructions of their president. And their having that belief was a foreseeable consequence of the growing crescendo of false statements, conspiracy theories, and reckless hyperbole which the defeated president kept shouting into the largest megaphone on planet Earth. The issue is not only the president's intemperate language on January 6th….It was also the entire manufactured atmosphere of looming catastrophe—the increasingly wild myths about a reverse landslide election that was being stolen in some secret coup by our now-president."

McConnell rejected the notion that Trump's rhetoric was typical of the language commonly used by politicians and that it is therefore unreasonable to blame him because some of his supporters took him more literally than he intended. "The leader of the free world cannot spend weeks thundering that shadowy forces are stealing our country and then feign surprise when people believe him and do reckless things," he said. "Sadly, many politicians sometimes make overheated comments or use metaphors that unhinged listeners might take literally. This was different. This was an intensifying crescendo of conspiracy theories, orchestrated by an outgoing president who seemed determined to either overturn the voters' decision or else torch our institutions on the way out."

McConnell also noted that Trump's "unconscionable behavior" continued after the riot started: "Whatever our ex-president claims he thought might happen that day, whatever reaction he says he meant to produce, by that afternoon, he was watching the same live television as the rest of the world. A mob was assaulting the Capitol in his name. These criminals were carrying his banners, hanging his flags, and screaming their loyalty to him. It was obvious that only President Trump could end this. Former aides publicly begged him to do so. Loyal allies frantically called the administration. But the president did not act swiftly. He did not do his job. He didn't take steps so federal law could be faithfully executed, and order restored."

To the contrary, "according to public reports, he watched television happily as the chaos unfolded. He kept pressing his scheme to overturn the election! Even after it was clear to any reasonable observer that Vice President Pence was in danger, even as the mob carrying Trump banners was beating cops and breaching perimeters, the president sent a further tweet attacking his vice president. Predictably and foreseeably under the circumstances, members of the mob seemed to interpret this as further inspiration to lawlessness and violence."

While Trump urged his supporters to "stay peaceful" in a tweet he posted an hour and 45 minutes after the riot began, McConnell noted, "he did not tell the mob to depart until even later"—more than three hours after the protest turned violent. "Even then," McConnell said, "with police officers bleeding and broken glass covering Capitol floors, he kept repeating election lies and praising the criminals."

McConnell's indictment of Trump, which elaborated on his previous criticism of the former president's conspiracy mongering and his role in provoking the riot, could have come straight out of the arguments made by the House managers charged with prosecuting the former president. Why did McConnell nevertheless vote to acquit Trump?

"Former President Trump is constitutionally not eligible for conviction," McConnell said. "There is no doubt this is a very close question. Donald Trump was the president when the House voted, though not when the House chose to deliver the papers. Brilliant scholars argue both sides of the jurisdictional question. The text is legitimately ambiguous. I respect my colleagues who have reached either conclusion. But after intense reflection, I believe the best constitutional reading shows that Article II, Section 4 exhausts the set of persons who can legitimately be impeached, tried, or convicted: the president, vice president, and civil officers. We have no power to convict and disqualify a former officeholder who is now a private citizen."

Since the Senate had a week to try Trump while he was still president, that gloss is misleading. McConnell refused to call the Senate back into session for a trial, and on Saturday he reiterated his view that "the Senate was right not to entertain some light-speed sham process to try to outrun the loss of jurisdiction." McConnell's position, in short, was that a trial in January would have been too soon, while a trial in February was too late. That conundrum only reinforces the argument that precluding the Senate from trying a former president frustrates the goals of accountability and deterrence by leaving Congress with no recourse against a president who commits "high crimes and misdemeanors" toward the end of his term or who resigns after his misconduct comes to light.

McConnell acknowledged that Trump could have been convicted even if his conduct did not qualify as incitement to riot under federal law or exceed the bounds of constitutionally protected speech described by the Supreme Court in the 1969 case Brandenburg v. Ohio, which held that even advocacy of lawbreaking cannot be criminally prosecuted unless it is not only "likely" to result in "imminent lawless action" but also "directed" at that outcome. "By the strict criminal standard, the president's speech probably was not incitement," McConnell said. "However, in the context of impeachment, the Senate might have decided this was acceptable shorthand for the reckless actions that preceded the riot."

Notwithstanding what Trump's lawyers claimed, the observation that his words were protected by the First Amendment was not a compelling argument against holding him responsible for neglecting his duty, abusing his power, and betraying his oath to uphold the Constitution in the context of impeachment. But if Trump were prosecuted or sued for his role in the riot, the First Amendment argument probably would be decisive. McConnell nevertheless held out the vain hope that Trump could still be held accountable in civil or criminal court. "We have a criminal justice system in this country," he said. "We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one."

McConnell rightly noted that Trump's misconduct was not limited to what he did on January 6. Trump promoted his fantasy of a stolen election for months, repeatedly telling his followers that allowing Biden to take office would destroy democracy and ruin the republic. What was McConnell doing while Trump did that? Not much.

McConnell, unlike some of his Republican colleagues in Congress, did not acknowledge Biden's victory until December 15, the day after the Electoral College met. While he did not join the Senate and House Republicans who lent credence to Trump's delusion, he did not contradict it either, even though it was clear by mid-November that there was no credible evidence to back it up.

McConnell did finally criticize Trump's "sweeping conspiracy theories" when Congress convened to tally the Electoral College votes on January 6. He noted that "nothing before us proves illegality anywhere near the massive scale…that would have tipped the entire election." Forcefully rejecting other Republican senators' legally groundless objections to Biden's electoral votes, he said "public doubt alone" cannot "justify a radical break" from historical practice "when the doubt itself was incited without evidence."

By this point, McConnell perceived a threat far more serious than his party's loss of a presidential election. "If this election were overturned by mere allegations from the losing side, our democracy would enter a death spiral," he warned. "We would never see the whole nation accept an election again," he added, and "every four years would be a scramble for power at all cost."

McConnell's repudiation of Trump's outlandish election-fraud claims came a bit late, as he soon discovered when he was forced to flee the president's enraged fans. A few days later, he said the "violent criminals who tried to stop Congress from doing our duty" by invading the Capitol on January 6 were "fed lies" and "provoked by the president and other powerful people." That statement jibed with the essence of Trump's impeachment, which McConnell reportedly favored in the hope that it would help the Republican Party separate itself from Trump's personality cult. But by the time the Senate voted on whether to proceed with Trump's trial, McConnell seems to have changed his mind, agreeing with 44 other Republicans that the Senate no longer had jurisdiction over Trump, the position he reiterated on Saturday. (After hearing the arguments on both sides of the issue, two of those senators—North Carolina's Richard Burr and Louisiana's Bill Cassidy—decided the Senate had jurisdiction after all and voted to convict Trump.)

Why did McConnell wait so long before acknowledging reality and rejecting Trump's baseless allegations? "I defended the president's right to bring any complaints to our legal system," he said on Saturday. "The legal system spoke. The Electoral College spoke. As I stood up and said clearly at the time, the election was settled."

That excuse is hard to swallow. Trump was asserting that he actually won by a landslide immediately after the election, based on nothing more than the typical ups and downs of election night vote tallies. His lawsuits never even alleged anything like the massive criminal conspiracy that he and his allies described in speeches, press conferences, tweets, and TV interviews. The legal complaints the campaign did raise were almost uniformly rejected by the courts. That pattern was obvious long before McConnell admitted that Trump had lost.

By November 20, the day after the Trump campaign's lawyers held a bizarre press conference at which they laid out a convoluted conspiracy theory that would eventually lead to defamation suits seeking billions of dollars in damages, Rep. Liz Cheney (R–Wyo.), the third-ranking Republican in the House, was emphasizing the lack of evidence to support the president's outlandish charges. "The president and his lawyers have made claims of criminality and widespread fraud, which they allege could impact election results," Cheney said. "If they have genuine evidence of this, they are obligated to present it immediately in court and to the American people."

McConnell did not implicitly express similar doubts until mid-December and did not make them explicit until the day of the Capitol riot. Nor did he say anything about Trump's determination to overturn the election results through extralegal means by pressuring state officials and stirring his supporters against them, which predictably led to threats of violence that Trump blithely ignored.

"Mr. President," a Republican election official in Georgia pleaded on December 1, "stop inspiring people to commit potential acts of violence. Someone's going to get hurt. Someone's going to get shot. Someone's going to get killed." That was two weeks before McConnell conceded that Biden had won the election and more than a month before he publicly criticized Trump's allegations, belatedly acknowledging the danger they posed to democracy, public order, and the peaceful transition of power.

Cheney joined nine other House Republicans in voting to impeach Trump, saying "there has never been a greater betrayal by a President of the United States of his office and his oath to the Constitution." McConnell ultimately decided Congress had no remedy for that betrayal. Seven of his Republican colleagues disagreed, 10 short of the number required for conviction but still an unprecedented endorsement of an impeachment by members of the president's own party.

McConnell's compromise seems to be aimed at appeasing the majority of Americans who supported Trump's impeachment without alienating the majority of Republicans who did not. According to a Monmouth University poll conducted in late January, 56 percent of Americans thought Trump should have been impeached, while 42 percent disagreed. A smaller majority, 52 percent, favored conviction, which 44 percent opposed.

The partisan breakdown was predictable: Only 13 percent of Republicans supported impeachment, compared to 92 percent of Democrats, and just 11 percent of Republicans favored conviction, compared to 87 percent of Democrats. Most independents (52 percent) supported impeaching Trump, but a plurality (48 percent) opposed convicting him.

The poll also found that most Republicans (72 percent) still believed Biden won the election "due to voter fraud." On a slightly more encouraging note, just 36 percent of Republicans thought Trump "did nothing wrong" on January 6, while 53 percent thought "some of Trump's conduct was improper" but not impeachable and another 10 percent thought it was "definitely grounds for impeachment." In other words, more than three-fifths of Republicans believed there was something amiss in trying to stop Biden from taking office by telling a mob of angry supporters to march on the Capitol.

McConnell evidently concluded that he could safely amplify that unease as long as he did not express it with a vote to convict Trump. But such triangulation does not bode well for the GOP's ability to come up with an agenda that goes beyond blind loyalty to a sore loser whose desperation to maintain power at all costs was obvious long before McConnell decided to decry it.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Enough of this BS about conspiracy theories. The perps admitted stealing the election in this week's Time magazine, and laid out how they did it. There is no further doubt to give them the benefit of.

That article says nothing of the sort. It details how both left and right wing groups worked to help Biden, but they did not nothing illegal.

The, "Hey, let's conspire to violate election laws" part was certainly illegal.

Would be if it had happened.

Lefties admitted it. The SCOTUS is hearing the cases.

Oh hey, it's the ever delusional LC

SCOTUS is hearing the cases??

Show us the docket sheets, or shut up.

Brett, if you’re looking to Molly for honest intellectual discussion, you are wasting your time. Molly is incapable of any useful discussion, honest or intellectual.

This is the same "bragging about how we did it" article from 2016.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/01/us/politics/obama-trump-russia-election-hacking.html

Back then it was in the New York times. Administration officials bragged about how they "rushed to distribute classified information about Russian collusion around the government in order to protect it."

At the time astute observers noted that we had actual high government officials admitting to committing felonies in order to sabotage the incoming administration. What couldn't be known for certain at the time was that the only reason anything was classified was in order to cover up the fact that the whole thing was a hoax from the start.

Now you have the same article in Time.... a group who are "in on it" and are so excited about what they did that they cannot help but brag about it.

They use the identical spin language. "We had to preserve the election!" is what they claim this time. Last time it was "We had to preserve evidence of Russian collusion!".

It is the thinnest of veneers. This is OJ writing "If I did it".

If you are a credulous team player, you can hang your hat on the spin - that it was necessary to rig the election in order to "preserve democracy". When blinded by partisan politics, people do stupid things like this.

But make no mistake, this is the same article. You probably read the NYT article from the same moment in 2017 and don't see anything other than patriotic Americans saving us from the Russians.

They both are public confessions of attempts to subvert the American government. It doesn't take a great deal of insight to see through the thin layer of spin. If you can't see through it, you are what they like to call "useful idiots", your mind so clouded by tribal affiliations that you are happy to proclaim that there are five lights.

Well said, as usual

This is ridiculous.

Neither article says what you claim they do.

I can only assume you're hoping people don't read either article and just take your opinion on face value.

Seriously... your commentary is ridiculous. there's no other way to say it, and no need to say it any other way.

Actually, he boiled it down to the nub: 'we had to preserve the election' and 'we had to preserve evidence of Russian collusion' are the excuses the Donkeys and their pud-suckers have used.

Two articles about the duopoly's hissy fit 2.0 by libertarians are two articles too many.

It details how both left and right wing groups

Did you read the same article I did? The one I read gave no actual detail about any "right wing groups". The same way the same sorts of people have "a black friend".

Commies at unreason wont even cover that article.

Democrats started civil war 2.0 and they are not doing well. el presidente biden cant get any legitimacy for his banana republic position. commie democrats cant even get RINOs to prevent Trump and his libertarian-ish movement from destroying the democrat party.

I'm waiting to hear you in the news one day having fully snapped.

It’s not a lie… if you believe it.

That's true. It's also ironic for Reason to attack McConnell for only figuring out the truth fairly late, given that Reason's criminal-justice reporting has been plagued by even bigger errors that it has taken longer to admit were false. For example, Reason helped peddle the false "Hands Up, Don't Shoot" narrative about Ferguson that was later debunked as false even by the Obama Justice Department.

Two Reason staffers peddled the false “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” narrative about Michael Brown’s death being a racist murder, even though Michael Brown never said those words, and he wasn’t murdered. Even the left-wing black Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart has admitted that “‘Hands up, don’t shoot’ was built on a lie.” Even the woke Washington Post fact-checker Michelle Ye Hee Lee has explained that “‘Hands up, don’t shoot’ did not happen in Ferguson.”

The Washington Post reported in 2015 that Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson “was justified in shooting Brown,” according to the Obama Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. “It was reasonable for police Officer Darren Wilson to be afraid of Michael Brown in their encounter last summer, a Justice Department investigation concluded, and thus he could not “be prosecuted for fatally shooting” Brown, reported the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

An 86-page report by the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division found that both physical evidence and “credible” witnesses supported Officer Wilson’s version of an incident that triggered looting and rioting in Ferguson. As the Civil Rights Division concluded on page 82 of that report, “the shots fired” by Wilson after Michael “Brown turned around were in self-defense.” Indeed, “several of” the mostly black “witnesses stated that they would have … responded” as the police officer did in shooting Brown.

Reason's reporting in many areas is excellent. But its criminal-justice reporting, sadly, often falls short -- gullibly repeating claims that death-row inmates are innocent, even when court after court has reviewed their convictions and explained why they are guilty as sin.

Trust Reason's reporting -- unless it involves criminal-justice issues, where Reason's soft-on-crime attitude sometimes makes it swallow falsehoods.

“Michelle Ye Hee Lee...”

Haha. No way. Please tell me that’s a tranny.

But what you missed is that the Michael Brown case was not just a normal criminal justice case. It was the birth of a movement. #BLM was created out of that moment.

There were weeks of riots after the shooting. Weeks where BLM gained traction as the story of the racist police officer shooting an unarmed "gentle giant" for no reason at all while his hand were raised and he begged not to be shot was repeated and amplified across the nation.

But why were there weeks where the story was repeated like that? Police obviously heard the officers version of events the same day. They also knew immediately that there was forensic evidence to prove that our "Gentle Giant" had reached inside the vehicle through the window and attempted to take the officers gun. So why was the story never refuted?

Well......

The Obama administration sent in Holder and the DOJ to investigate racism and corruption in the police. They ordered everyone in the local government to be silent while the FBI and DOJ investigated. Speaking to the press would be interfering with an ongoing investigation - an investigation that might just toss you in jail, or see you fired for crimes of racism... so you'd better comply.

Weeks go by. National progressive organizations move in quickly, taking over the ground game in Ferguson within a couple of days. They build a national movement to protest this obviously racially motivated cold blooded murder.

And Holder says nothing.

Without doubt Holder and his team knew that "Hands up, don't shoot" was a lie within 24 hours of arriving in Ferguson. They not only had the officer's story, but the initial reports of the shot fired inside the car and into the door, blood inside the car the wound to Brown's hand, and the statement from the lady who was driving by and was only a couple dozen feet away as she witnessed the struggle in the car window.

But they said nothing. Not one word as buildings burned. Not a word as angry young people stormed local interstates, risking their own death and the death of innocent motorists to protest this murder.

Weeks go by. Businesses are getting destroyed. Protests are organized around the country.

Not a word.

Then, finally... once they've gotten all the mileage they can out of it.... the DOJ issues their report. "Hands up, Don't shoot!" never happened. The officer didn't just stop a gentle giant for no reason. In fact, he was a suspect in a strong-arm robbery only minutes earlier where he assaulted a shop owner.

Why? Why sit silent as riots spread? Why press the narrative that the officer was a violent racist, even after African-American eyewitnesses countered your version of events? If your motivation was truly justice, would you follow that path? If finding the truth was the goal, is that what you would do?

Why indeed....

Your narrative makes the release of that video of Brown even more amazing.

The video where the gentle giant was strong-arm robbing a convenience store clerk not 45 minutes before his stupid, violent ass was bleeding to death on that street.

Did we ever get a leak about his, no doubt lengthy, juvenile criminal record?

But but but he shouldn't have gotten killed over some Swisher Sweets! And poor Saint Martin, killed over some Skittles and watermelon drank. 🙁

This is a post that could be pinned somewhere. Good summary.

Why? you ask.

Easy. The Donkeys and other race-mongers make hay off of any divisive racist incidents that might happen. And if there aren't any REAL racist events, they will simply make them up. From whole cloth if necessary. And they do that because deep down they are racists, and can keep black people continually agitated and angry by playing the race card over and over and over. The NYT WaPo LATimes etc are yellow journalism for the 21st century.

The race-mongers have been working overtime, ever since the ultimate proof was exposed that this isn't a racist nation - the election of a black man to be president, TWICE.

They lost their ability to claim what every sane person knows, we aren't these irretrievable racists they want say we are, to use against the country.

So, they ignore that and double-down on the fraud.

The Senate minority leader's triangulation does not bode well for the GOP's ability to stand for something

other than a personality cult.FTFY. The GOP stands for nothing but keeping the grift going.

Jacob Sullum has deep concern for the future of the Republican party, along with an abiding respect for the opinions and positions of Mitch McConnell.

Good day, sir.

This is exactly the lesson you should have learned. The real party is "the Establishment". The machine feeds cash into the government-corporate monster. That's all it does. Everything else is window dressing.

That is why they were so violent in turning on an outsider like Trump. He was upending all of those apple carts. One of the first thing he did when he got in office was to renegotiate the contracts on refurbishing Air Force One. He cut the cost of that by a huge percentage. They still did the same job, they just got paid less.

This is a tiny window into "how things are done". Huge profit margins on government contracts. Limited utility.

We have visibility on stuff like the Space Launch System (SLS), a rocket that was to replace the shuttle, mandated by congress to use "off the shelf components" in order to make it cheaper and to get it built faster. Congress has doled out over $20 billion on the program (more if you count the predecessor program that was cancelled). And still no SLS... a rocket that will cost over a billion dollars per launch. In the same time frame, SpaceX has developed the Falcon9 rocket, made the first stage reusable, developed the Falcon Heavy which does a major chunk of what SLS is designed to do, and is now fast developing the Starship rocket which will eclipse the SLS by a wide margin. All for just a few billion dollars. They developed 4 new rocket engines in the process - the Merlin, Draco, Super-Draco and the new Raptor. An entire Starship with its tens of Raptor engines will cost less than a single RS-25 on the SLS (and it uses 4). And Starship is completely reusable. SLS will dump the whole thing in the ocean.

This is why it has been dubbed the Senate Launch System by critics.

Why do I ramble on about an obscure space program? Because it is tiny.. a drop in the bucket. But it demonstrates the problem in obvious and impossible to deny terms.

Why would Goldman Sachs so vehemently support a leftist like Obama? Well, don't listen to the rhetoric. What happened? Goldman raked in billions upon billions from the government. So did all of wall street. Just handing out cash for nothing.

Mcconnell and Obama are on opposite sides of the aisle. But they are on the same team.

And you are not part of the team - whether you be a democrat useful idiot, or a republican useful idiot. Abortion, racism, sexism, terrorism.... those are just the tools they use to keep you in line while they siphon off the cash.

"Why would Goldman Sachs so vehemently support a leftist like Obama? Well, don’t listen to the rhetoric. What happened? Goldman raked in billions upon billions from the government. So did all of wall street. Just handing out cash for nothing."

How large was the projected market for carbon credit trading, if Al Gore had won in 2000? I recall it being in the 10s of billions, back when a billion was real money. How much will a replacement market with the West all within the Paris Accords? And GS was set to take their arbitrage fees.

Nothing of value created, but a whole lot of wealth shifted from many people to a few.

Again, the naked assertion that personality cults are worse than blind socialism while ignoring the fact that the only reason personality cults are in any real way a bad thing is because of socialism.

You pay Trump rent, and he lives in your head rent free.

Fortunately it's a spacious apartment in Sullum's empty head.

Anyway is reason finally done espousing conspiracy theories and mind reading and performance art? Or can we expect more of these retarded articles describing events that didn't happen, while ignoring real riots this past summer that did.

Hard being reminded you supported a dangerous grifter for four years.

Easy to remind you that you're a TDS-addled shit who was more than happy to get Biden.

And a liar besides; tell us about how the cop was killed by the protesters again, asshole. It's amusing.

He was killed by the protestors. It is clear he didn’t just die that night by coincidence.

He was only hit in the head with a fire extinguisher and apparently sprayed with bear spray. Just another peaceful protest. I believe there was one stroke and one heart attack (tRumpters aren't in the best shape). One trampling and one shot (while trying to cross a barricade).

Question: Had the protesters caught Pelosi, what would they have done?

You've got a couple of "asserted without evidence" moments in your compilation there.

Reports out of the medical examiner's office refute the story you were initially told.

Dunno what the truth is. But I know who was lying.

He's compounding the lie as well. The bear spray is an unfounded and unprovable rumor. For all we know in that regard, Sicknick brushed up against someone who had gotten sprayed or even got incidentally tear gassed by fellow officers. We do know that he texted his brother that he got pepper sprayed, which is not something you normally do when suffering the effects of tear gas or pepper/bear spray.

Either way, tear gas/pepper/bear spray doesn't cause strokes and no court of law would hear a murder case where random individuals pepper sprayed someone with intent to cause a stroke. Which is why they haven't charged anyone with jack shit.

WK, Biden has only been in office less than FOUR WEEKS. I know you’re dumb, but even you should do better than that.

And in four weeks he has shown himself to be more dictatorial than Donald Trump ever was.

Unprecedented number of executive orders and memos; many damaging to the economy Trump made explode.

And if you supported Biden, there's a grifter of 40+ years. Nice.

Maybe you liked Harris. She's only less bad because she hasn't played the game as long.

There are a lot of stupid criticisms of Trump running around. "Grifter" is one of the dumbest.

In the last election we had the Buffoon that is Trump - a bull in a China shop smashing and destroying things all across the federal government.

And we had a guy who is openly on the take. They didn't even have a good lie - so their cover story is the dual laughers of "it has been debunked" and "his son was just trading on his name".

You do know that "trading on his name" is synonymous with "on the take", right? They mean exactly the same thing.

Of all of the "shit for shinola" stories the press has been able to sell in my lifetime, getting people to ignore the Biden-Ukraine story has to be the most impressive. You have a quid-pro-quo bribery story where we have the quid (getting a prosecutor fired) and the quo (millions of dollars paid to his son)... both publicly admitted in their own words, as well as documented by 3rd parties.... and the press was able to sell "there is no evidence" to an unskeptical audience.

The entire government is a grift. Whether through incompetence or because he truly wanted to hack away at the graft, Trump was the enemy of the grifters.

But he's the grifter.

Jeez.

People will repeat literally anything they are told to repeat, no matter how stupid.

They didn’t even have a good lie – so their cover story is the dual laughers of “it has been debunked” and “his son was just trading on his name”.

You do know that “trading on his name” is synonymous with “on the take”, right? They mean exactly the same thing.

Remember when Bush II was the embodiment of the corrupt nepotism that pervades our government?

McConnell slams Trump for like 10 minutes, and you end with "blind loyalty to a sore loser". Hmm.

McConnell didn't "explain" anything but his OPINION of what Trump did.

The opinion of a Trump-hater, like B...er...Mitch, is not worthy of attention, except to other Trump-haters - a sure minority in the country.

If you're a libertarian you should trust the public's judgment in not voting for a bad candidate as opposed to demanding that the Senate make such decisions for us. McConnell made the right choice here. Now it's up to we the people to make our case to our fellows.

I think Trump is smart and brave. The problem was that his followers are lazy, hypocritical cowards. And he knew it, which was why he thought his only option was to try to radicalize a few impressionable patsies to storm the capitol. And he did, and it predictably failed miserably. And they will all turn against him at the trials.

But I'll still gladly support Trump if he becomes more libertarian and advocates ending social security and medicare (socialism). Of course you'll say that's suicidal. But it's the only way. Touch the third rail - you'll be fine.

Like in 2016 when the majority of voters voted for Clinton and Trump won anyways? I'm supposed to trust that? Granted we can't trust the senate either as McConnell demonstrated.

If you were a libertarian then it wouldn't matter who wins because government would have little power. But you're a socialist, depending on the day. (And the fact that you're running rampant on here shows why Trump lost, even if you don't trust the results.)

When were the rules changed to majority voting for electing a president?

^Exactly -- hint, hint; The *United* States...........

Because the federal isn't a [WE] mob - it's a Union of States.

How are Medicare and social security socialism? What means of production do they own? They are simply means for income redistribution.

Either you're a socialist-in-denial or you just want to quibble with your allies. Not sure which is worse.

income redistribution - means of production.. Seriously?

I guess in our current environment where the USD has increasingly Less/No representational value of production one could come to such a blind assertion.

How are Medicare and S.S. socialism; it's just funny money. It's not like it's going to be used to obtain any production. 🙂

“If you’re a libertarian you should trust the public’s judgment in not voting for a bad candidate as opposed to demanding that the Senate make such decisions for us.”

Seems orthogonal to liberty. The Republican voter base seems to be open to voting in authoritarian madmen. The Democrat voter base seems open to voting in socialism. The Senate seems spineless and not particularly interested in guarding our liberty. There’s no great libertarian angle to any of these powers.

You're just a defeatist. You won't lead or follow, so get the heck out of the way.

The trick to touching the third rail is to jump onto it with both feet, and hold your balance so that you don't fall off. This could work with Socialist Insecurity and MediCant too, if we could find someone brave enough to just do it.

Hahaha!

Content free signaling to fellow right wingers. Classic RMac.

Fry more.

What I hear from all of this "he's guilty of what he's accused of, but the charge and the proposed punishment are obscene."

Has no one thought of the precedent here? I fully expect that if the Republicans get the House in the midterms, Biden will face impeachment for his bribery scandals. There is far more evidence of far worse activity than what Trump was accused of.

If Harris is president at that time, I fully expect her to be impeached for her role in the 2020 riots. No matter what you thought about Trump, the fact is that he stopped when things got out of hand. Harris continued to promote the riots and explicitly urged violence even after people began dying.

I fear that we have passed the Gracchi threshold. Now that impeachment has become an explicitly political tool, we will have constant impeachments. This cannot end well.

When did Trump stop when things got out of hand?

He told people to stop rioting and peacefully go home on the 6th.

After a while, when he got around to it.

A lot faster than any democrat ever did over the hundreds of riots perpetrated by their minions last year.

Goddamn you’re such a shitweasel partisan hack.

The much-maligned money quote was

"Go Home, I love you, you're very special".

Trump was mocked mercilessly for it, until people decided to pretend that he kept urging people to murder everyone and incite an insurrection.

At that point, people tried to pretend it didn't happen.

Yertle the turtle

Was king of the pond

A nice little pond

It was clean it was neat

The water was warm

There was plenty to eat

Until one day

The king of them all

Decided the kingdom

He ruled was too small

I'm a ruler of all that I see

But I don't see enough

And that's the trouble with me

Dereliction of duty?

If Trump had sent Troops to the Capitol the instant headlines on the Internets would have been:

Trump Launches Military Coup

Armed Troops Reinforce Trump Brownshirts at Capitol

I doubt if Trump sent reinforcements they could have restored order any faster than it was actually done. The resumed counting the votes and certified the election late that night.

You're right! People would have said mean words about Trump no matter what he did! That is why you ignore what people are saying and do the right thing anyway.

Which he did and you lie about.

Sevo, do you acknowledge that McCarthy was asking Trump to call off his mob, that Trump was watching the rioting on TV, and he still waited hours to do anything. Do you acknowledge that he told McCarthy that the rioters cared more about the stolen election than he did?

To my knowledge McCarthy has not confirmed that story. Odd that.

Yes, why did the shampeachment managers want to call the recipient of the story, rather than the one, who supposedly told the story.

P.S. Just because Trump said this, if he did, about the protesters, doesn't mean he wasn't going to do something about trying to get them to stop.

McCarthy wasn’t begging Trump to send in troops. He was begging Trump to make a statement to call off his rioting supporters. Trump blew him off.

Even on a long list of idiotic narratives, this one is pretty dumb.

Do you suppose that the dude with the buffalo hat was checking the TV to see if Trump made any statements while he was LARPing in the Capital?

Don't be so easily manipulated.

Yeah, saw few TV's amongst the crowd.

...probably why it was not "mostly peaceful"...

Mitch is just dishonest and that is all there is too it. He would have voted Not Guilty no matter what and he just made up an excuse. I am disappointing that he did not use a better one. It shows just how little he cares about even pretending to look honest.

Shut up. You’re an inveterate liar and Marxist minion. You know nothing of honesty, other than referencing it to advance a Marxist partisan position.

I think we can all agree that McConnell is scum, but what does that have to do with Trump? McConnell isn't part of the Trump faction within the GOP, he's a Trump foe without the honestly to admit it.

Trump was probably Mcconnell's last choice, but he was a good soldier for Trump. I don't think you can name a single Trump initiative that died in the Senate with the exception of the Obamacare repeal bill McCain killed. Nobody could have finessed McCain, but I don't think anyone could have done a better job keeping Collins, Murkowski, and Romney somewhat in line. Don't forget those first 2 years the majority depended on Corker, Alexander, and Flake, as well as McCain, Collins, and Murkowski.

Mcconnell was hardly responsible for that.

Umm, I think it was McConnell who was the one effectively calling the shots while pretending it was Trump's idea all along.

You have all sorts of fantasies, and a very loose acquaintance with reality.

McConnell is absolutely in the Trump faction. McConnell protected Trump from impeachment conviction twice. McConnell has also lied for Trump, coddled Trump, and let Trump get away with everything he wanted.

"McConnell protected Trump from impeachment conviction twice."

Bullshit, lefty asshole; there were never enough votes to convict Trump in both those witch hunts.

"McConnell has also lied for Trump, coddled Trump, and let Trump get away with everything he wanted."

You.

Are.

Full.

Of.

Shit.

Three times.

McConnell very easily could have decided that Trump was too risky and unstable (both proved true) going into the 2020 elections and thought Pence on the top of the ticket would be better. He could have whipped enough Senators to convict Trump the first time. It would have been even easier to whip another 9 senators this time around.

McConnell is a shrewd politician and could have gotten Trump convicted. He could have declared the second impeachment trial a complete farce and boycotted it, thus putting on a big show and still allowing Trump to be convicted.

Nope, you’re a moron. Filled with democrat fever dreams and stupid, evil ideas.

McConnell’s biggest flaw to Molly is he’s more politically astute than she is.

No one pay Molly for political analysis.

McConnell protected Trump from impeachment conviction twice.

Hogwash. Trump wasn't going to get convicted, because the charges in both instances were bullshit, and there just weren't enough jealous little bitches like Romney, or Arlen Specter wannabes in the Senate willing to piss off their constituents just to poke Trump in the eye.

If McConnell had tried to beat the drum to convict Trump on bullshit charges, he'd be out at the next primary season just like Liz Cheney will be.

-jcr

Really? It only took McConnell's vote and no on else's to protect Trump from impeachment? I thought it was super majority, but maybe it must be unanimous as you state.

Is there anyone within a hundred miles of DC that is not an idiot, liar, attention whore, crook, and/or opportunist?

A few people of integrity, scattered here and there. But, for the most part, you are correct.

We both lived through the last four years, Sullum and I, but I have a tremendously different lived experience of them.

What can you expect from the liar who claimed Trump literally told people to drink bleach?

Anti-White liberals and respectable conservatives that support massive third-world immigration and forced assimilation for EVERY White country and ONLY White countries say that they are anti-racist, but their policies will lead to a world with no White people i.e White Genocide. Anti-racist is a code word for anti-White.

Fuck off and go back to stormfront.

Wow... that's a dumb whitewash.

Clearly not a conservative or a real white nationalist.

Probably a sock for one of the professional agitators.

Larkenson posts that same shit a lot. I think he is some kind of white nationalist. Or someone fishing for people with that kind of belief.

Fucking useless jackass.

Who cares? I look forward to a world with way more mixed race people and I couldn’t care less if any pure white people are around in a hundred years.

Haha. Yeah. White people are terrible.

I don’t care if America is white. I care that America is American, and democrat free.

How racist can you get?

What does this mean??? Just a diversity word salad response.

You knew there was going to be one more Sullum article.

"one more". You're more of an optimist than I am.

It would be interesting if millions of say Irish or Italian or German Americans decided to immigrate to Mexico or Israel what the response of the population would be...maybe it's more of a normal human response to mass immigration of differrent cultures/ethnicities who don't share similar political views..who knows..

America is supposed to be better than that. America is supposed to be a melting pot and a beacon of hope to all the people of the world.

That was fine when there was two billion people on the planet. 8 billion, many in poverty, not so much.

Progressives sure do like to live in the past.

Do you have any empirical evidence to support your assertion that America can’t absorb more immigrants?

"689 million people live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than $1.90 a day... In the United States... 38.1 million people, live in poverty — with an income of less than $33.26 per day"

EGV's assertion was more similar to "We can't absorb an unlimited number of immigrants, considering the current population of the world."

I bet 500 million+ people of the world would love to come to the US if given the chance. The poor of the US live better than a billion others out there.

A melting pot since 1965. Such illustrious history.

“Standing for something”, ignoring counter evidence is bigotry.

Trumps team demonstrated with evidence the hypocrisy of the baseless charge of “insurrection”.

Are you pining for bigotry?

So, we are just going to ignore the revelation of McCarthy’s call to Trump, and Trump’s blowing off his request for Trump to call off his supporters. Got it.

More prog lies from a prog liar.

He isn’t lying

Possibly not. Lies require intent. Instead of a lie he might be stupid enough to believe what he says.

Are you talking about when trump said to be peaceful?

Trump was under no obligation of any kind to repeat anyone’s request verbatim.

"Are you talking about when trump said to be peaceful?"

Did he also say that Brutus was an honorable man?

LOL

Ok then take that case for incitement to a court of law since Trump is a private citizen

Go ahead and present that “evidence” in the same way

And you’ll be in jail for contempt of court. What an F-ing joke

Don't worry. They will. There are likely to be dozens of cases brought against Trump. They have stopped even pretending that the rule of law matters.

They had no problem using the FBI, DOJ, CIA and State Department against Trump - before and after he was elected. The New York attorney general ran for office on a promise to user her office to "Get Trump".

They not only use the power of government to attack political enemies, they openly advocate for more of the same.

I don't know where you've been for the last few years - but simply go look up the case of Michael Flynn. A guy who was provably framed by the Obama administration (including the new President who was personally involved). Even after that proof was released - the courts protected the interest of the people who framed him. At all levels they insisted that he be punished - for the crime of being associated with Trump. In an amazing coincidence, the full panel of the appeals court heard cases for Hillary Clinton and Michael Flynn on the same obscure issue (mandamus) within a week of each other... and reached exactly the opposite ruling. It was so ludicrous that they even acknowledged it in the Clinton ruling, saying that there was no contradiction because ... uh.. reasons. (the facts in the Clinton case were much weaker than the facts in the Flynn case, yet they ruled in her favor and against Flynn - the opposite of the result you'd expect based on their reasoning).

Trump is an anomaly. His wild and seemingly undirected gyrations have revealed the machine behind the façade. The courts have been no exception. We have even seen the courts rule - within days of each other - "you lack standing because you have suffered no harm" and "the harm is done, so Laches applies. You have no standing". Can't sue to stop them from doing something because it is too early. Can't sue after it is done because it is too late.

Yeah.. don't count on the courts.

"The Senate minority leader's triangulation does not bode well for the GOP's ability to stand for something other than a personality cult."

All the Senate needs to stand for is opposing the Green New Deal, opposing the Democrats' attempt to rob us of our gun rights, opposing Medicare for All, opposing bailing out California's, Illinois', and New York's unfunded pension obligations, and opposing packing the Supreme Court. If they stand for that, they'll be as principled as they need to be.

You know what would have helped that cause? If Trump, Lin Wood, Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, and “the pillow guy” hadn’t discouraged Republican voters from voting in the Georgia runoffs.

Yep, all those Reason articles detailing the extreme leftism and general lunacy of the Democrat candidates were unneeded warnings.

Oh, wait.

You think what Reason did or didn’t write had a significant effect on the election outcome?

Anything purporting to be “non-partisan” producing independent reporting that went against or countered the mainstream would have been more influential than peddling the main narrative with doubled -down obfuscation and outright lies.

yup.

When it comes to you WK - Why is it always Trump's fault?

Hmm, So I'm for a smarter push for "Green New Deal" (based in science), pro gun rights, pro some form of universal health insurance (voucher for everyone that files a tax return... hmm isn't that what Obama Care was supposed to be?), unfunded pensions is typically rise in health insurance (see above), and yeah, no packing supreme court.

Now Republicans have been particularly bad at the science thing (Democrats have their... 'challanges' as well - right Gore?)

Bottom line, I want something in the middle of Democrat and Republican

No party is the 'party of science'. They both pick and choose what they want to promote.

The smartest Green New Deal is no Green New Deal. People have been revealing their preference for warmer climates for decades, moving to the South and West. Why blow 2 trillion we don't have on fighting the weather, when it most likely won't work anyway?

People will start to use cleaner cars (electric or hydrogen powered) and cleaner energy when they are superior in quality and lower in price than the oil-economy alternatives we have now. Otherwise we'll all be nagged like Californians to use less electricity between 4 and 9 PM to "keep California Golden".

Fat chance of any of that happening (unless there is a secret agreement behind closed doors as to which things the establishment wants killed).

They already waived the white flag on bailing out all the failing democrat states with their ludicrous public pension fund issues.

They won't be making any "unapproved" stands.

Jacob, just stop it. You sound like a naked shill for Team Blue. Why would you think someone with an open mind would find your slant persuasive? Or... was that ever the point?

He is..rationalizes degenerates like "cuties", seems to have contempt for libertarians who care about national boundaries as the best insurance for liberty....like so many at Reason seems to be more in line at Slate or Salon or the NYT...hell he would fit in there well at those places (Wapo as well) where if your Irish or Italian..you better not apply...

Well people did die...two policemen in NYC and I think seven Dallas PD when Obama did nothing to dispel the false Ferguson narrative. Where was JS then? Where was Reason then? Both Biden and Obama knew Ferguson was bs...or should have and they did nothing to get in front of the fake story...seriously more people were killed with Ferguson's fake narrative than the unarmed idiots who entered the Capital building...again Reason has shown it's very far left when push to come to shove hypocrisy.

Libertarians showed horrific judgement when many urged people to vote for Hillary and then Biden. There is a libertarian wing to the GOP and if you are in a party you back its candidates. There is no pro-freedom wing of the Democratic Party. It does not exist. If you are not going to make alliances and run candidates the way communists and socialists do you are a joke party. More importantly even if you win everything Democrats did to Trump: fake sex dossier, attacks on his wife, false accusations of being in a spy ring with Putin, they will do to a libertarian 100 fold. And there will be no reason for the GOP to defend you.

If you are going to play the game you must learn the rules.

Here's a quote to think about:

Vice President Kamala Harris could be conceivably impeached for the exact same charges that Democrats levied against Trump.

"We've opened Pandora's box to future presidents," Graham said.

"If you use this model, I don't know how Kamala Harris doesn't get impeached if the Republicans take over the House, because she actually bailed out rioters and one of the rioters went back to the streets and broke somebody's head open," Graham explained. "So, we've opened Pandora's box here and I'm sad for the country."

"He is the first president to ever be impeached without a lawyer, without a witness, without an ability to confront those against him and the trial record was a complete joke, hearsay upon hearsay," he added.

I think you need to understand the Democratic Party. click on PLAY ALL : https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLoyRsCV7lLcdcjXO1JkUNUTXcSeiHIBiN

I guess you don't understand. About 55% of the country think tRump is an asshole. Not that Biden will be the best President ever, just that tRump is an asshole.

tRump is a liar, a cheater on taxes, bank loans, SATs, and of course his wife. He dodge the draft while denigrating veterans that gave a hell of a lot more for their country. He's been accused of sexual misconduct over 25 times including toward 15 yr olds. He is no business genius, any money he's ever made was buying and selling properties (makes the average car salesman a business equal) - on top of which he declared bankruptcy 6 times leaving hundreds to pay for his mess.

So forgive us if we shake our heads or make fun of tRumptards who make excuses after excuses for tRumps piss-poor behavior.

Its kinda like watching a relative who calls you up and says they are going to be a millionaire because of this Nigerian prince that is going to hook them up.

Too many lies to bother with. It’s all been litigated and debunked so many times. If you be,I eve the bullshit you write, then you are a weak, stupid drone for the progs. If you don’t actually believe it, then you are a conniving, lying shitweasel shill for the progs.

Either way, you’re a treasonous oxygen thief that has no business existing. Please self correct.

What's been debunked about President Bone Spurs ducking out on the draft with a note from a doctor that lived in one of his father's buildings? What's been debunked about his dubious tax schemes? His own former lawyer has said on the record about how he would routinely inflate his properties' values for loan applications while depressing them for tax purposes. One or both of those would be fraud. This is one of the many things that will be investigated thoroughly now that he isn't a sitting President with an AG to act as his personal defense attorney.

I suppose you also buy his weak explanation about that Access Hollywood tape being "locker room talk" rather than the warped way that he views women. It was either a confession or at least a fantasy of his to think that he was so awesome for being rich and famous that he could get away with sexual assault. Maybe you believe that there really was a VP of the Trump Organization named John Barron that would speak on his behalf in the '80s. Or that his "assistant", John Miller, told People that Madonna wanted to go out with him once Trump had to admit under oath in a deposition that he had used John Barron as a pseudonym. Or that it was someone named David Dennison that was part of the hush-money scheme for Stormy Daniels and Playboy playmates.

Trump was always a joke. But now, his biggest fans refuse to laugh at the joke they played on themselves and the country by voting for him.

We get it - Trump is evil in everything he's ever done or will do, yet somehow never been prosecuted for any of it...

Go away

And yet Trump supporters are in the cult of personality.

Vice President Kamala Harris could be conceivably impeached for the exact same charges that Democrats levied against Trump.

No, she can't. The charges against Trump were bullshit because everything he said is protected by the first amendment, and that applies to everything she's said, too.

If you want to impeach Willie Brown's whore, you'll have to go for crimes she committed before Biden gave her a job she doesn't deserve. I think her attempt to get a man killed by withholding the DNA evidence that sprung him from death row would be a good issue to impeach her for.

-jcr

I think you miss the point.

They just established the precedent.

You can (and should) be impeached if you say something and then people who support you do something violent. Hell, some lawmakers even called for him to be convicted of first degree murder.

But the House voted to impeach explicitly because he gave a speech that said he wanted to protest the certification of the election, and then people attacked the capital.

That is the new standard. That is what Graham warned against.

Harris and other democrats explicitly supported violent acts by their supporters. They even offered financial help for those accused of criminal acts.

The democrats set the standard that the first amendment does not apply to impeachment. They didn't do this implicitly - several of them openly said exactly this.

They were warned that getting rid of the filibuster was a dangerous precedent. The democrats thought they had a permanent majority, so they did it anyway rather than compromise with Republicans. And then they squealed like pigs when it was used against them.

Right now Team D thinks they have a permanent majority. They see how easily the media and tech companies were brought to heel and how eagerly they serve. They saw how easily election laws were modified to favor them... and now they salivate with thoughts of a final death blow by packing the courts and bringing on 2 new democrat strongholds as states.

So they have no fear that any such thing will happen.

But the wind doesn't always blow from the west. And we shall see what happens when the winds shift. Team R usually doesn't follow suit on things like this... but something changed with "the nuclear option". I'm not at all convinced that they wouldn't retaliate in kind.

And as a second warning - the democrats have promised criminal prosecutions against Trump and his supporters. We really don't want to walk down that road.

"Harris and other democrats explicitly supported violent acts by their supporters. They even offered financial help for those accused of criminal acts."

You should look up what "explicitly" means. Have any quotes of Democrats "explicitly" supporting violent acts? And if people are "accused of criminal acts", they are entitled to an adequate legal defense. That's guaranteed by the Constitution, you know. Trump made noise in 2016 about paying legal bills for supporters at his rallies if they dealt with protesters. Did he pay the legal bills of the guy that sucker punched a protester at one rally as he was being led away? He suggested that he would look into doing that at the time.

"The democrats set the standard that the first amendment does not apply to impeachment. They didn’t do this implicitly – several of them openly said exactly this."

You are oversimplifying this. The 1st Amendment does not protect incitement to violence at all, not just during impeachment. But that isn't the issue anyway, as you should know. Impeachment isn't a criminal trial, so the charges do not need to be held to the same standard as criminal liability. Trump probably could argue the 1st Amendment successfully for any attempt to prosecute him criminally or to hold him civilly liable for damages for things he said in regards to the riot. But as President, he has duties to uphold as part of his job. Impeachment is a process for firing him and possibly for barring him from future office, not prosecuting him. So, the standard is whether he violated his oath of office with what he said, not whether his words meet the high criminal standard for incitement. Incitement generally requires intent to provoke violence, but Trump's words certainly rose to the level that violence could be predicted to occur because of what he said. That he also threw in a word or two about being "peaceful" doesn't do enough to negate all of the apocalyptic rhetoric about losing their country if the MAGA crowd didn't do something strong enough.

Disagree with the conclusion if you must, but the argument that Trump was at least playing with fire and should have known it is valid. We should hold our leaders accountable if they recklessly inflame the fringes to the point where they believe that the leader wants them to go all "1776" despite a couple other words about being "peaceful".

"They were warned that getting rid of the filibuster was a dangerous precedent. The democrats thought they had a permanent majority, so they did it anyway rather than compromise with Republicans."

"But the House voted to impeach explicitly because he gave a speech that said he wanted to protest the certification of the election, and then people attacked the capital."

He was doing more than arguing for a "protest" against the certification. He wanted it stopped. He wanted Pence to unilaterally declare disputed Electoral Votes invalid. He wanted the crowd to cheer on the Republicans objecting as if that would encourage enough Congresspeople to change their minds and actually stop the certification. You all seem to keep believing that Trump was just trying to have his say, but that isn't plausible. By late December, if not sooner, Trump seemed to sincerely believe that the election was stolen from him, just as most of his supporters did. He wasn't going to settle for simply protesting the hand over of power to Biden.

As for the judicial filibuster, McConnell wasn't interested in 'compromise' with Obama over judicial appointments. His Senate minority was only interested in obstructing as many judicial nominees as possible. It was always his vision to remake SCOTUS and the rest of the the federal courts in a Federalist Society image, and he got it done once he became Majority Leader in 2015 and was able to block almost all of Obama's nominees. That left plenty of openings for a Republican in office in 2017 to start filling them with whomever they felt like approving.

The filibuster wasn't used so heavily to obstruct the majority's efforts to legislate or the President's ability to appoint judges and executive branch officials until fairly recently in history. One side or the other "nuking" it was inevitable with the way it was being used. Compromise with the minority party to achieve actual bipartisan results requires that the minority party acknowledges that they are the minority party. They didn't win enough seats, so they can only get a little of what they want and can only block a little of what the majority wants. That's the point of having elections.

"You should look up what “explicitly” means. Have any quotes of Democrats “explicitly” supporting violent acts?"

There were none of Trump doing so yet, well, he got impeached again...

How many more pixels will be spent on this nothingburger? What could matter LESS to my life than whether a person who is no longer in the seat of power is impeached or not?

I'm saddened, but not surprised, by the amount of angst that fills my newsfeed about this. People have so much of themselves wrapped up in this non-event. Some are celebrating an acquittal (for a political, not legal, proceeding), and some are despairing over the end of the republic that the non-president was not convicted of something...anything.

How much of your personal well being are you going to hand over to these horrible people in Washington who don't know you, nor care one shit about you? I'll save my outrage for an actual issue.

If I'm upset about anything, I'm upset that no witnesses were called. We'll now never hear from the DC Mayor, the Nat'l guard, the DC Police, or anyone who knows the inner workings of what went down that day because the House didn't have the stones to call them forward and ask them the questions that actually matter.

You do realize _you_ are the one providing the pixels, don’t you?

Reason is buying server time, disk space, and network bandwidth. They put zero pixels into the scenario where _you_ are displaying Sullum’s writing on _your_ screen.

Poor, eternally victimized , helpless right wingers.

You’re right about one thing. We should never be victims.

You should be, and are a victim. First of your own stupidity, and also of the garbage you consume from your prog masters.

Just because someone's guilty of what the House accuses him of is not a reason to vote to convict him. You also need to establish both that there was a specific criminal act meeting all the legal elements and that conviction is genuinely necessary to protect the public.

Where do I get this standard? Oh, just from the man who was the presiding officer at this trial, Senator Patrick Leahy, D-VT. It's the standard he personally promulgated back in 1999.

Jacob should be ashamed by the implications of your post.

But he lacks any such capacity.

Either that, or he really has been hiding his affection for McConnell all along.

If Sullum is not trolling, he's replaced his keyboard several times as the spittle has shorted-out the key contacts.

He needs professional help either way.

On a scale of 1-10 how triggered are you by Sallum’s posts? 1 is slightly triggered and 10 is melting down because dear leader has been critiqued.

You’re a dopey cult member. Go away!

Cult member or not, anyone who would post that is clearly projecting.

“You also need to establish both that there was a specific criminal act”

No, you don’t. Impeachment is about abuse of office. There is no bar that requires proof of a criminal act.

So Obama does get impeached next time the House flips.

Correct. These people think they’re awfully smart but they are some of the dumbest people I’ve ever seen commentate one the World Wide Web.

You might want to consider clicking the link in the post you're responding to.

Look up! There's the point whooshing over your head!

The presiding judge of the hearings disagrees

...well, when his team is in trouble, I mean.

McConnel truly believes censorship instead of authentication will SAVE the USA. What a buffoon.

As long as Gov-God "saviors" pretend in their own minds that the people aren't concerned about election fraud it will just go away..

Why don't you lazy, incompetent prom kings introduce some legislation and a serious investigation into what 80% of the people are concerned about???????????????

At least McConnel gets one-thing right, "We would never see the whole nation accept an election again and every four years would be a scramble for power at all cost."

Now that you've correctly identified the problem how about correctly identifying the solution.

Hey, here’s an idea. Get active in the state you live in, and work toward improving your election laws and processes. Volunteer as a poll worker next time. Stop griping, be a constructive adult and do something positive about it.

^Probably the wisest words you've said in the last few days...

However; the fact that my county requires ID, Keeps it's registered voter tab current, didn't see a 90% favor at 3 A.M. or ballots pulled from under tables after sending everyone home, doesn't use foreign made machines with proprietary foreign code and online connection during processing and expectantly went 70% in Trumps favor in both in-person and mail-in (consistency).

While also nullifying federal over-reach that is UN-Constitutional. There's only so much I can do in 'My State'.

Good news. There were no places that used voting machines with foreign code and online connections during processing.

Here’s proof of election fraud.

Manual recounts demonstrated that thousands of votes were flipped from Trump to Biden in the voting machines.

Refute any of the evidence in the video or admit you’re lying.

http://www.worldviewweekend.com/tv/video/absolute-proof-exposing-election-fraud-and-theft-america-enemies-foreign-and-domestic

Lol none of that happened

Lol, yes it did.

‘Lol’.

Which "none" do you refer to?

I was up watching the election. I watched officials in multiple cities send poll watchers home, saying the count would resume late in the morning. I don't need Snopes or anyone else tell me whether it happened. It was on CNN, live.

I watched video of ballots being pulled from under a table. Nobody even argues that it didn't happen. "That didn't happen" isn't even claimed. The claim is that there was nothing nefarious about it.

We did indeed see huge changes in vote totals posted by states in the middle of the night that were entirely for one candidate. This has been explained as simple glitches and mistakes by data entry personnel. But nobody claims "that didn't happen". You can claim that the interpretation is wrong (it was a favor is an interpretation). But you can't claim it didn't happen.

This is a great job of gaslighting Trump supporters. First set up conditions of the election such that, if Trump wasn't cheated, you sure make it look like he was. Then label you crazy for drawing an inference that you'd be naive not to. Then pretend that behaving politically in response is pathologic, and make the president look like a criminal for reacting the way sensible politicians do, i.e. by appreciating their supporters.

“sure make it look like he was”

Nobody was making it look like he was except Trump and his mouthpieces.

No he was actually cheated. So no one had to make anything ‘look’ like anything else. As you are a known liar and propagandist, with no real intellect or integrity, your constant denial just showcases the truth.

Your prog masters committed widespread fraud, and violated dozens of election laws to usurp the presidency for a senile man who is provably in the pocket of the Chinese.

That you are an enthusiastic shill for all this is disgusting. I hope you are one day lawfully executed for your Marxist advocacy, and other treasonous actions. Which is far better than you deserve.

"Your prog masters committed widespread fraud, and violated dozens of election laws..."

And I seriously doubt that you would have any idea which states violated which laws. This is just a talking point that the Trump supporters that masquerade as journalists repeat, bringing on people that will echo this without any pushback.

You what happens when one side sees procedures being planned that they think, in good faith, are illegal? They file lawsuits and use lawyers with experience and specialty in election law. When the first judge doesn't rule their way, they appeal, and appeal again until the highest court in the state or the SCOTUS rules or declines to take the appeal. At that point, they've done what they can and look to legislatures to change the law to make it so that judges have no room to disagree.

What do they not do? If acting on good faith, they do not wait until just before the voting starts or after the results go against them to challenge the procedures. Voters deserve to have the rules set and finalized before they start voting. They also don't look at what they admit are procedure issues, without even alleging that there were fraudulent ballots, and then call for hundreds of thousands of votes to be outright discarded. They also don't make these challenges only in areas where their opponent's voters are most numerous, but ignore that the same flaws that they are alleging exist in areas where their candidate is strong.

If the GOP/Trump side had stuck to the first version of disputing election procedures, they might have actually won some of their cases instead of losing them all.

"This is a great job of gaslighting Trump supporters."

Trump supporters have learned how to use the term "gaslighting" because of how often Trump engaged in it.

Pretty pitiful that Sullum has nothing to do but continuously write anti-Trump or anti-election fraud articles. Obviously being paid to do so.

So stop reading him then lol

Great article Jacob, thanks for writing it. You know it’s good when triggered MAGA disguising themselves as “concerned libertarians” come out in force to defend dear leader. These are some really sick people who should pursue help for their mental ailment.

Trump had his faults but he's still the least bad US president since Calvin Coolidge. I had hopes he might surpass ol' Silent Cal, and I think he's up to it but we'll probably have to wait till 2024 to make it happen in 2025, 2026, 2027, 2028 and...

he’s still the least bad US president since Calvin Coolidge

I disagree. I'd say that Eisenhower was a decent human being, and that's why we don't think about him much.

-jcr

He spent the last six months of his presidency trying to undermine American democracy, which culminated with his supporters trying to take the Capitol building by force. That's is not a "least bad US president".

icandrive is talking policy, not speeches.

Yeah, so it was just my imagination that state election rules and procedures were illegally changed without the approval of the state legislatures. Stop gaslighting us. Or, more colloquially, don't piss down my neck and tell me it's raining. THEY STOLE THE ELECTION

Are you as upset that state election rules and procedures were changed in Texas, by its governor, without legislative involvement?

Trump was not guilty, and his lawyers proved it. Mitch and Nancy are guilty, they knew, they did nothing. That is why McConnell is now lying. It is amazing how far Reason has sunk. It is now a liberal hate magazine.

McConnell is not a practicing attorney, and his contempt for the first amendment disqualifies him to make a rational judgement on this question.

Trump did not incite the riot, no matter how many times the lefturds repeat this stupid lie. The riot was planned weeks before the event.

-jcr

The specific charge was "Incitement", not dereliction of duty. It is possible that Trump was guilty of a political offense but not the one the House charged him with. Impeachment for a president exists because the theory is that a sitting president cannot be criminally charged until he is out of office. Trump is out of office, he no longer has the protection from the office from criminal prosecution, but would any of these charges stand up in a court of law beyond a reasonable doubt.

"That conundrum only reinforces the argument that precluding the Senate from trying a former president frustrates the goals of accountability and deterrence by leaving Congress with no recourse against a president who commits "high crimes and misdemeanors" toward the end of his term or who resigns after his misconduct comes to light."

When Nixon resigned, the House chose not pursue impeachment further, as the aim of impeachment was achieved.

So what do we do about the current President, who seems to be a puppet for authoritarian madmen.

New York Times Retracts Story Claiming Capitol Officer Brian Sicknick Was Killed in Riot - bigleaguepolitics.com - Published 8 hours ago on Feb 14, 2021 - By Richard Moorhead

The New York Times retracted a story claiming Capitol Police Officer Brian Sicknick died as a a result of being struck by a fire extinguisher during the January 6th Capitol riot on Sunday.

“Law enforcement officials initially said Mr. Sicknick was struck with a fire extinguisher, but weeks later, police sources and investigators were at odds over whether he was hit. Medical experts have said he did not die of blunt force trauma, according to one law enforcement official.”

A formal autopsy report is yet to be released in regards to Sicknick’s death, a highly unusual situation, especially with the event colored with controversy. The New York Times spread the idea that the New Jersey Air National Guard veteran and longtime Capitol officer died as a result of injuries inflicted by a rioter. This now appears highly unlikely.