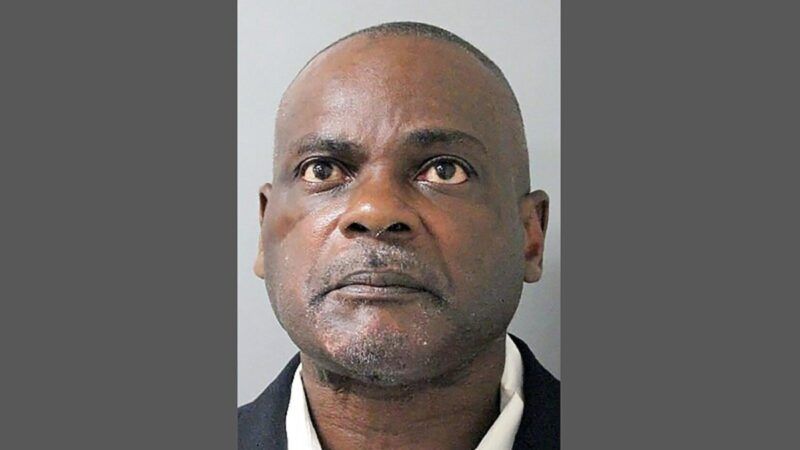

A Houston Drug Cop's Lies Sent This Man to Prison for 25 Years

The case shows how lax supervisors, incurious prosecutors, deferential judges, credulous jurors, and inattentive defense attorneys abet police misconduct.

Four years ago, Frederick Jeffery was sentenced to 25 years in prison for possessing five grams of methamphetamine—a bit more than the weight of a single sugar packet. That draconian punishment, which was enhanced based on prior convictions, was appalling enough by itself. But now it turns out that Jeffery was convicted based on lies, as he has always insisted.

Harris County, Texas, Judge Stacy M. Allen yesterday recommended that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reverse Jeffery's conviction, saying it resulted from "a pattern of deceit involving fictional drug buys, perjured search warrant affidavits, and false testimony to a jury." The Houston narcotics officer who framed Jeffery, Gerald Goines, is the same corrupt cop who used similar methods to instigate a January 2019 drug raid that killed Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas, a middle-aged couple whom Goines falsely accused of selling heroin from their home at 7815 Harding Street.

"Frederick Jeffery's case is a due process disaster," said Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg. "In the wake of Harding Street, it is clear that Gerald Goines and other members of the Houston Police Department Narcotics Division engaged in a years-long scheme involving fictional drug buys, perjured warrants and phony overtime. Individuals like Frederick Jeffery were collateral damage."

Jeffery's case is about more than one bad cop. His arrest and conviction show how lax supervisors, incurious prosecutors, deferential judges, credulous jurors, and inattentive defense attorneys let bad cops send innocent people to prison.

In a search warrant affidavit he filed on October 25, 2016, Goines swore that a confidential informant had bought marijuana two days earlier from "a black male" who was about 30 years old and "known by the street name of 'B'" inside a house at 2807 Nettleton Street. Based on that information, Goines wanted to search the house, which is where he arrested Jeffery on October 27. In a separate incident report, Goines said the same informant had bought crack cocaine at 2811 Nettleton Street, next door to the house where she had supposedly bought marijuana, the following day.

The informant, "C.I. #5696," was the same woman who Goines would later claim had bought black-tar heroin from a middle-aged "white male, whose name is unknown," at 7815 Harding Street. After the Harding Street raid, she denied that she had made any such purchase, which Goines admitted he had invented.

In a recorded interview with Houston police on November 7, 2019, three months after Goines was charged with murder in connection with the Harding Street raid, the C.I. likewise said she had not bought crack at 2811 Nettleton Street. She said she and Goines "started doing things 'the wrong way' about three or four years prior to the interview," Judge Allen writes. "She would get paid for some buys she did not actually make." But the C.I. "was not questioned about 2807 Nettleton specifically."

On Monday, nearly three years later, the Harris County District Attorney's Office did ask the informant about the purported marijuana purchase. She "stated that she did not make a buy at 2807 Nettleton and has never made a buy on Nettleton Street." Allen notes that Jeffery's arrest "would not have occurred but for the perjured search warrant affidavit and resulting warrant."

When Goines and Sgt. Brent Batts arrived to serve that warrant two days later, Goines testified, he saw Jeffery and another man, Orville Jackson, standing on the front porch. According to Goines, Jeffery was locking the burglar bars covering the front door. Goines said he found a set of keys, one of which fit the front door and one of which fit the burglar bars, on the front lawn.

Jackson, who allegedly "tossed a bag of crack cocaine onto the grass," was arrested for possession of that drug. On a table inside the house, the officers found bags of pills that, according to subsequent testing, contained 4.7 grams of methamphetamine, which Goines linked to Jeffery. During the ensuing arrest, Goines claimed, Jeffery asked for his cellphone, which he supposedly said was on the table where the cops found the pills. Goines said that is also where he found the phone.

Jeffery said that conversation never happened. "The conversation was not recorded and no other officers heard it," Allen notes. According to Goines' incident report, "officers did not activate their body-worn cameras until transporting the suspects to the jail." Goines did not mention the purported conversation in that report but claimed to remember it 18 months later at Jeffery's trial.

Jeffery denied that the phone was his, adding that cellphone records would confirm that point. In body camera video recorded after the arrests that was released to Jeffery's attorney before the trial, Jackson says the cellphone is his, while Jeffery says, "I ain't got no motherfucking phone."

That exchange by itself should have been enough for reasonable doubt about the alleged link between Jeffery and the phone, which in turn supposedly proved that the methamphetamine was also his. The lack of video showing what happened before the arrests was also suspicious. Jefferey alleged that "the officers altered, disposed of, and/or erased exculpatory camera footage."

Allen says the trial judge allowed the prosecution to rely on Goines' account of what Jeffery had said because Jeffery "was not being interrogated" at the time. "Based on Goines' false testimony," she writes, "the trial court denied [Jeffery's] motion to suppress and admitted evidence about the phone to the jury."

Batts took pictures of the table but "could not point out to the jury the cell phone in the photos he took." Goines "agreed that some photos do not clearly show what is on the table, and it took a moment for Goines to testify about what he felt was the cell phone in the photo."

Allen notes that Goines was "the only witness who can connect [Jeffery] to the drugs that were found inside the house." He was the only person who claimed to see Jeffery locking the burglar bars, the only person who claimed he saw the keys "near [Jeffery's] hand," the only person who confirmed that the keys fit the burglar bars and the front door, the only person who claimed to hear Jeffery acknowledge ownership of the phone, and the only person who claimed he had seen the phone on the table near the pills. In short, Allen says, "the difference between charging [Jeffery] and not Jackson with possession of the drugs inside the house is solely based on Goines' testimony."

In 2020 and 2021, Allen notes, the Court of Criminal Appeals agreed that Goines had lied to implicate two brothers, Otis and Steven Mallet, in a 2008 crack cocaine sale. Both men were eventually exonerated.

Otis Mallet, who always maintained his innocence, had served two years of an eight-year prison sentence before he was released on parole. Steven Mallet spent 10 months in jail before pleading guilty as part of a deal that did not require him to spend any more time behind bars. "He pled guilty because he had been in jail for 10 months and they were offering him a deal basically for time served," said public defender Bob Wicoff. "This happens a lot where people have to get out and resume their lives. They [have] jobs and families, [so] they plead guilty even when they're not just to get out."

The appeals court "determined that Goines has a propensity to be untruthful in his undercover drug assignments," Allen notes. It "further determined that Goines testified falsely." In Jeffery's case as in the Mallet cases, "Goines invoked the Fifth Amendment and remained silent" rather than respond to the allegation that he had lied.

Last May, an investigator with the district attorney's office examined the cellphone that Goines said belonged to Jeffery. Allen says he "determined that the cell phone number was 832-988-3406." Unrelated incident reports "show that a woman named Bridgette Black claimed her phone number was 832-988-3406 on May 13, 2016 (months before [Jeffery's] arrest) and on November 7, 2016 (less than two weeks after [Jeffery's] arrest)." Allen adds that "there is no mention of [Jeffery] or a connection between Ms. Black and [Jeffery]."

Allen concludes that "Goines testified falsely that [Jeffery] claimed ownership of the phone that was recovered from 2807 Nettleton." That testimony was crucial to Jeffery's conviction, because the prosecution argued that he "should be convicted of possessing illegal drugs because he owned the cell phone located near the drugs."

Since much of this information was available at the time of Jeffery's 2018 trial, it is not surprising that he claimed "ineffective assistance of counsel." But Allen did not think it necessary to address that claim, since Goines' false statements in his search warrant affidavit and his perjury during the trial were more than enough to invalidate Jeffery's arrest and conviction.

"The evidence developed post-conviction reveals a pattern of deceit involving

fictional drug buys, perjured search warrant affidavits, and false testimony to a

jury," Allen concludes. "Confidence in the criminal justice system cannot tolerate such behavior."

Yet for years, possibly decades, the criminal justice system in Texas did tolerate, or at least overlook, such behavior. Goines, who faces federal civil rights charges as well as state charges in connection with the operation that killed Tuttle and Nicholas, was employed by the Houston Police Department (HPD) for 34 years before he retired in the wake of that raid. Investigations of the HPD's Narcotics Division triggered by that fiasco revealed a pattern of lax supervision, sloppy practices, and fraud that extended far beyond Goines. As a result of those investigations, local prosecutors charged 11 other officers—including Steven Bryant, the cop who backed up Goines' account of a heroin purchase on Harding Street that never happened—with various crimes.

"Prosecutors dismissed dozens of Goines' cases and began reviewing thousands of Goines' past convictions," The Houston Chronicle notes. So far, Jeffery's case is one of five in which the district attorney's office has recommended that convictions be reversed.

But for the lethal Harding Street raid, these miscarriages of justice might never have been recognized, even though Goines had a long history of dishonesty. In Jeffery's case, there were plenty of clues that Goines could not be trusted. While Allen cites "the evidence developed post-conviction," that evidence could and should have been developed before Jeffery was sent to prison.

To help justify a no-knock search warrant, Goines claimed his C.I., who had never actually visited the house, saw "a rifle" near the front door. But no such weapon was recovered during the search. That is similar to what happened in the Harding Street case, where Goines claimed the same informant, who again had never visited the house, had seen "a semi-auto handgun of a 9mm caliber" that police did not find.

After the Harding Street raid, KHOU, the CBS station in Houston, examined 109 cases in which Goines had obtained drug search warrants since 2012. In 96 percent of the cases, Goines claimed a no-knock warrant was justified because "knocking and announcing would be dangerous [and] futile," the same language he used in seeking no-knock warrants for the Harding Street and Nettleton Street houses. "In every one of those cases in which he claimed confidential informants observed guns inside," KHOU reported, "no weapons were ever recovered, according to evidence logs Goines filed with the court." Evidently no one noticed that suspicious pattern until it was too late for Tuttle and Nicholas.

In that case as in Jeffery's, Goines did not even bother to ascertain who lived at the house he proposed to search. In both cases, magistrates quickly rubber-stamped the warrants without pausing to wonder about the thoroughness of Goines' investigation.

During Jeffery's trial, Allen notes, Goines contradictorily testified that he found the house keys on the ground, that Jeffery "was actually holding the keys," that "he saw [Jeffery] touching the keys only when [Jeffery] was locking up," and that "he never saw [Jeffery] throw the keys" and "only saw the keys on the ground by [Jeffery's] hand." As for the cellphone, Jackson said it was his. Police, prosecutors, or Jeffery's lawyer easily could have investigated that claim by examining phone records. Until last May, it seems, no one even bothered to discover the number attached to the phone and ask whether it was connected to Jeffery.

How often does this sort of thing happen? There is no way to know. Judges and jurors tend to discount the protestations of defendants like Jeffery, especially if they have prior convictions, and automatically accept the testimony of cops like Goines, who are presumed to be honest and dedicated public servants. Goines was a 34-year veteran whom Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo hailed as a hero after the cops killed Tuttle and Nicholas during an operation based on nothing but Goines' unverifiable word and a neighbor's false tip. Until that story unraveled, it never entered Acevedo's mind that Goines might have made the whole thing up.

Such a possibility rarely occurs to jurors either, even though drug cases often hinge on a single cop's account of what happened, drug buys that may be fictional, and evidence that may have been planted. Yet we know from the Houston scandal and similar revelations in cities such as New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco that police corruption, abuse, and "testilying" are more common than jurors imagine, especially in drug cases.

"Police officer perjury in court to justify illegal dope searches is commonplace," Golden Gate University law professor Peter Keane, a former San Francisco police commissioner, observed in 2011. "One of the dirty little not-so-secret secrets of the criminal justice system is undercover narcotics officers intentionally lying under oath. It is a perversion of the American justice system that strikes directly at the rule of law. Yet it is the routine way of doing business in courtrooms everywhere in America."

During jury duty in Dallas several years ago, I was screened for a drunk driving case. Probing my attitude toward police, a prosecutor asked how much weight I would give an officer's testimony about the circumstances of a DUI arrest. As much weight as any other person's, I said, and maybe less. In any case, I said, I would definitely want to see evidence of intoxication that went beyond the arresting officer's claims. Needless to say, I did not serve on that jury. I probably should have been less candid.

When theoretically intolerable police behavior is tolerated in practice, prosecutors will have more and more difficulty seating juries—a point brought home by a scene in the HBO series We Own This City, which chronicles the Goines-like activities of the Baltimore Police Department's Gun Trace Task Force. A judge questioning potential jurors finds that one after another has had a bad experience with Baltimore cops or knows someone who has. "Is the evidence coming from the Baltimore police?" one asks. "'Cause if that's the case…I know they ain't gonna have no problem lying."

Show Comments (54)