The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent | Est. 2002

Life as an Academic Defender of the Intuitively Obvious

Academics are supposed to discover nonobvious, counterintituitive truths. But, especially in recent years, much of my work involves defending positions that seem obvious to most laypeople, even though many experts deny them.

Academics are supposed to find counterintuitive, nonobvious ideas. That should be especially true for me, given that I hold many unpopular views, and am deeply opposed to populism of both the left and right-wing varieties. A Man of the People I am not.

But, especially in recent years, much of my work actually consists of defending intuitive ideas against other experts who reject them. When I describe these issues to laypeople, I often get the reaction that the point in question is just obviously true, and incredulity that any intelligent person might deny it.

Some examples:

1. Widespread voter ignorance is a serious problem for democracy. Academic experts have generated a large literature trying to deny this; I critique it in works like Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter. It is ironic that this anti-populist idea is, on average, more readily accepted by ordinary people than by academic experts. But that's been my experience over more than 25 years of writing and speaking about this subject.

2. "Public use" means actual government ownership and/or actual use by the public, not anything that might benefit the public in some way. The Supreme Court and lots of legal scholars disagree! See my book The Grasping Hand: Kelo v. New London and the Limits of Eminent Domain, for why they're wrong. In teaching cases like Kelo v. City of New London, I usually end up spending much of the time explaining why the Court's rulings might be right (even though I oppose them myself). Most students find these decisions intuitively repugnant, and it is my duty - as an instructor - to help them to see the other side.

3. "Invasion" means an organized military attack, not illegal migration or cross-border drug smuggling. The Trump administration, multiple state governments, and a few academics say otherwise. I have written various articles (e.g. here and here) and amicus briefs (see here and here) explaining why they're wrong.

4. The right to private property includes the right to use that property, and significant restrictions on the right to use qualify as takings of private property under the Constitution. The Supreme Court has long said otherwise, and lots of legal scholars agree. For why they're wrong, see my article "The Constitutional Case Against Exclusionary Zoning" (with Joshua Braver). I have a forthcoming book chapter that gets into this issue in greater detail.

5. The power to spend money for the "general welfare" is a power to spend for purposes that benefit virtually everyone or implement other parts of the Constitution, not a power to spend on anything that Congress concludes might benefit someone in some way. The Supreme Court disagrees, and so do most legal scholars.

6. The power to regulate interstate commerce is a power to regulate actual interstate trade, not the power to regulate any activity that might substantially affect the economy. Once again, the Supreme Court, plus most academics, disagree. When I teach cases that interpret the Commerce Clause power super-broadly, such as Wickard v. Filburn and Gonzales v. Raich, I often get the same kind of student reaction, as with Kelo, discussed above: the students intuitively hate these results, and I have to spend most of the allotted time explaining why the Court might be right.

7. Emergency powers should only be used in actual emergencies (defined as sudden crises), and courts should not assume an emergency exists merely because the president or some other government official says so. Instead, the government should bear the burden of proving that an emergency exists before it gets to exercise any emergency powers. A good many experts and judges disagree, at least in some respects, and so too do most presidential administrations.

In some cases, the above premises have counterintuitive implications, even fairly radical ones (this is especially true of points 1, 4, 5, and 6 above). But the premises themselves are intuitive ones that most laypeople readily accept, but many experts and other elites deny.

I do, of course, have various works where I defend counterintuitive ideas, such as these:

1. Immigration restrictions inflict enormous harm on natives, not just would-be immigrants.

2. Voting in elections does not create meaningful consent to government policies (see, e.g., Ch. 1 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom).

3. Racial and ethnic groups - including seemingly "indigenous" ones - do not have collective property rights to land that entitle them to exclude others (see Ch. 5 of Free to Move and this article).

4. Organ markets should be legalized, and are no more objectionable then letting people do dangerous work for pay, such as being a lumberjack or an NFL player.

But defending the intuitive and even the seemingly obvious is an outsize part of my publication record.

I certainly do not believe that intuitive ideas are always right, and counterintuitive ones always wrong. Far from it! If intuition were an infallible guide to truth on contentious issues, we wouldn't need expertise.

I am not entirely sure why I have ended up defending so many intuitive positions. One possibility is that I have much less love and patience for legal technicalities than many legal scholars do, and thus am more attracted to arguments based on fundamental first principles (many of which have an intuitive dimension). Also, as a libertarian in a field where most people have widely differing views, there may be an unusually large number of situations where my predispositions diverge from those of other experts, and some of them are also cases where the views of the field diverge from common intuitions.

That said, there is some advantage to defending intuitively appealing arguments in situations where the opposing view is either dominant among experts, or (as in the case of "invasion" above) has the support of a powerful political movement. Having intuition on your side makes persuasion easier.

In some cases where most experts oppose an intuitive view, it's because their superior knowledge proves the intuition wrong. But there are also situations where that pattern arises because of some combination of ideological bias and historical path-dependency. I think that is what happened in the property rights and federal powers examples, discussed above. It can also happen that such biases afflict commentators and government officials on one side of the political spectrum who have incentives to make it easier to implement "their" side's preferred polices (I think that is right now the case with "invasion").

If you can identify situations where a view widely accepted among experts or elites diverges from intuition without good reason, it creates opportunities for especially compelling books and articles. It's probably no accident that works defending intuitive views figure disproportionately among my most widely cited publications.

That said, I am probably not the most objective judge of whether I have identified the right intuitive ideas to defend. That question can't be answered just by relying on intuition! Readers will have to decide for themselves.

Federal Courts May Be Able To Receive Filings 24/7, But There Is No Expectation To Review Unanticipated Filings Overnight

If the Supreme Court wants to rebuke lower courts for not acting promptly enough, the Justices should police their own conduct.

In Trump v. CASA, Justice Kavanaugh extolled the power of the Supreme Court as a supreme institution. In the process, he took a not-so-subtle shot at the inferior courts:

But district courts and courts of appeals are likewise not perfectly equipped to make expedited preliminary judgments on important matters of this kind. Yet they have to do so, and so do we. By law, federal courts are open and can receive and review applications for relief 24/7/365. See 28 U. S. C. §452 ("All courts of the United States shall be deemed always open for the purpose of filing proper papers . . . and making motions and orders").

When I read this passage, I suspected it was a response to Judge Ho's concurrence in AARP v. Trump. Jon Adler read it the same way.

I first saw this statutory argument made by Adam Unikowsky. But I'm not sure it works.

First, as a threshold matter, the statute is limited to filing papers, not for the court to review or rule on those papers. Congress has established the Civil Justice Reform Act which tracks how many motions are pending for longer than six months. But there is no congressional deadline to actually decide cases.

Second, we should determine the original meaning of the statute when it was enacted. A version of this statute was passed back in 1948 (62 Stat. 907). Another version was passed in 1963 (77 Stat. 248). At either time, it would have been impossible to file papers overnight, unless special arrangements were made to keep the clerk's office open. There were no cell-phones, emails, or faxes. Even to this day, the Supreme Court closes in the evening according to the building regulation one. I don't think a pro se litigant can walk up to the Supreme Court a midnight an hand a brief to a Supreme Court police officer.

Thankfully, ECF allows late-night filings. But again, unless there is some way that judges are to be notified that important filings will be made overnight, there can be no expectation that judges can review those filings. Surgeons will keep pagers to alert them about emergency procedures. But Judges do not wear pagers that alert when a TRO is filed.

I will repeat the facts in AARP as many times as needed. The ACLU made a filing after midnight, and there was no notice in advance when the filing would made. There is no reasonable expectation that a judge will sit at his computer all night in anticipation of a possible filing. Judge Hendrix began to resolve the motion the next morning. Yet, the Supreme Court charged him with failing to respond to a motion filed overnight while he was sleeping. Facts are stubborn things.

Third, the Supreme Court has proven that it does not review emergency applications in a timely fashion. Justice Jackson let the emergency application in Libby v. Fectau sit several days without calling for a response. Eventually she called for a response, and the Court ultimately granted the application. Other justices have taken time to call for responses. Judge Hendrix's prompt attention was admirable. Justice Jackson's dilatory tactics were questionable. Even then, the Court can still sit on emergency petitions for weeks at a time.

Justice Kavanaugh observed:

On top of that, this Court has nine Justices, each of whom can (and does) consult and deliberate with the other eight to help the Court determine the best answer, unlike a smaller three-judge court of appeals panel or one-judge district court.

Whatever the timeline is for a single district court judge with a busy docket to rule, the timeline should be accelerated for nine Supreme Court Justices with a full complement of law clerks to decide.

I realize the thrust of CASA is that different rules apply to lower courts than to the Supreme Court. But if the Supreme Court wants to rebuke lower courts for not acting promptly enough, the Justices should police their own conduct.

Law360 Article About Disciplinary Charges Against Lawyer Was a Fair Report of Official Proceedings

From Mogan v. Portfolio Media, Inc., decided today by Seventh Circuit Judges Michael Brennan, Candace Jackson-Akiwumi, and Joshua Kolar:

Michael Mogan appeals the district court's dismissal of his suit against Portfolio Media, the owner of Law360, for defamation and false light. Because Mogan fails to show that any statement by Law360 falls outside the fair report privilege, we affirm the district court.

Mogan, who is an attorney, sued Airbnb in California state court on behalf of a client named Veronica McCluskey in 2018. After that case went to arbitration, Mogan sued Airbnb on his own behalf, also in California state court, for abuse of process and unfair business practices that he alleged Airbnb committed in the McCluskey case. The state court dismissed the case and imposed sanctions against Mogan for filing a frivolous lawsuit. When he refused to pay the sanctions, the California State Bar filed disciplinary charges against him. Law360, a legal news website, detailed these legal battles in three articles published between 2022 and 2023.

Publishing Private Phone Number May Be Tortious, Says Court in Case Brought by Shark Tank's Mr. Wonderful (Kevin O'Leary)

Defendant had 100K X followers, and as a result O'Leary "was flooded with unwanted communications."

From Judge Beth Bloom's order today granting default judgment in O'Leary v. Armstrong:

Defendant posted on X Plaintiff's private cell phone number and encouraged the public to harass Plaintiff, stating "[h]ave you ever wanted to call a real life murderer?! You can NOW! @kevinoleartyv is waiting for your call."

Following the post, Plaintiff began receiving communications from strangers who had obtained his number directly from Defendant's post. On March 20, 2025 at 11:32 a.m., Defendant stated he "was forced to delete the murderer @kevinolearytv's phone number by X. I was in X jail for 12 hours." As of March 19, 2025, the post had been viewed over 18,000 times.

{To state a claim for public disclosure of private facts under Florida law, "a plaintiff must allege (1) the publication, (2) of private facts, (3) that are offensive, and (4) are not of public concern."} By posting Plaintiff's private phone number to a social media platform on which Defendant had one million followers, Defendant published Plaintiff's private facts. The fact was offensive because, as a result, Plaintiff "was flooded with unwanted communications[.]" Although Plaintiff is a public figure, his personal contact information is not of legitimate public concern. Therefore, Plaintiff's well-pleaded factual allegations are sufficient [under the disclosure tort -EV].

The Supreme Court Is Supreme, And The Inferior Courts Are Inferior

Mi CASA no es su CASA

Trump v. CASA is one of the Supreme Court's most important decisions about the powers of the Supreme Court. It ranks up there with City of Boerne v. Flores, Cooper v. Aaron, and maybe even Marbury v. Madison. To be clear, CASA was not a ruling about the Article III powers of the lower courts. Justice Barrett was quite clear the Court was only ruling based on whether the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Our decision rests solely on the statutory authority that federal courts possess under the Judiciary Act of 1789. We express no view on the Government's argument that Article III forecloses universal relief.

CASA also did not directly discuss the Article III powers of the Supreme Court in particular. Instead, the majority seemed to accept the premise of judicial supremacy, at least based on the Solicitor Generals' representation. By contrast, Justice Kavanaugh embraced it wholeheartedly. In short, the Supreme Court is Supreme, and the inferior courts are inferior. Or, mi CASA no es su CASA.

Justice Barrett, citing her opinion in Brackeen, explains that a judicial opinion has no legal force. Rather, it is the judgment of a federal court that has force, and can remedy an injury.

In her law-declaring vision of thejudicial function, a district court's opinion is not just persuasive, but has the legal force of a judgment. But see Haaland v. Brackeen, 599 U. S. 255, 294 (2023) ("It is a federal court's judgment, not its opinion, that remedies an injury").

I disagree with much in Brackeen, but this statement is correct.

However, in Footnote 18, Barrett explains that the Supreme Court's opinions do have legal force. Or at least she quotes Solicitor General Sauer's representation on this point.

The dissent worries that the Citizenship Clause challenge will never reach this Court, because if the plaintiffs continue to prevail, they will have no reason to petition for certiorari. And if the Government keeps losing, it will "ha[ve] no incentive to file a petition here . . . because the outcome of such an appeal would be preordained." Post, at 42 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.). But at oral argument, the Solicitor General acknowledged that challenges to the Executive Order are pending in multiple circuits, Tr. of Oral Arg. 50, and when asked directly "When you lose oneof those, do you intend to seek cert?", the Solicitor General responded, "yes, abs olutely." Ibid. And while the dissent speculates that the Government would disregard an unfavorable opinion from this Court, the Solicitor General represented that the Government will respect both the judgments and the opinions of this Court. See id., at 62–63.

I'm not sure that Justice Barrett agrees with that statement. Indeed, Brackeen suggests just the opposite. But when the Solicitor General makes a representation, that representation is binding on the government. I agree with Jack Goldsmith that this acquiescence to judicial supremacy will come back to haunt the government for generations.

While Justice Barrett is perhaps tepid, Justice Kavanaugh fully embraces this species of judicial supremacy. He thinks it would be an "abdication" of the Supreme Court's "proper role" to let the lower courts make the "interim" ruling that would last for years.

That suggestion is flawed, in my view, because it would often leave an unworkable or intolerable patchwork of federal law in place. And even in cases where there is no patchwork—for example, because an application comes to us with a single nationwide class-action injunction—what if this Court thinks the lower court's decision is wrong? . . . . So a default policy of off-loading to lower courts the final word on whether to green-light or block major new federal statutes and executive actions for the several-year interim until a final ruling on the merits would seem to amount to an abdication of this Court's proper role.

Kavanaugh sees the Supreme Court's supremacy as either a matter of fact (de facto) or a matter of law (de jure). Descriptively, I probably agree with the former claim. Even before Cooper, the Supreme Court was the de facto body to resolve judicial conflicts. But the de jure claim to supremacy claim was only made in Cooper.

Second, if one agrees that the years-long interim status of a highly significant new federal statute or executive action should often be uniform throughout the UnitedStates, who decides what the interim status is? The answer typically will be this Court, as has been the case both traditionally and recently. This Court's actions in resolving applications for interim relief help provide clarity and uniformity as to the interim legal status ofmajor new federal statutes, rules, and executive orders. In particular, the Court's disposition of applications for interim relief often will effectively settle, de jure or de facto, the interim legal status of those statutes or executive actions nationwide.

Here, Justice Kavanaugh is embracing Cooperian supremacy. But Cooper did not concern the Supreme Court's power to issue universal injunctions. And that case concerned a ruling against state officials, not a coordinate branch of government. If the Court has the power to issue universal injunctions against the federal government de jure, that power would have to come from a statute or Article III itself. Justice Sotomayor raises this point in her dissent:

What, besides equity, enables this Court to order the Government to cease completely the enforcement of illegal policies? The majority does not say.

No, Justice Barrett does not say. If the Judiciary Act of 1789 does not give inferior courts the power to issue a universal injunction, where does the Supreme Court get that power? Justice Kavanaugh also does not say. And Justice Sotomayor thinks it is "naive" to believe the government would abide by this ruling "de facto."

So even if this Court later rules that the Citizenship Order is unlawful, we may nevertheless lack the power to enjoin enforcement as to anyone not formally a party before the Court. In a case where the Government is acting in open defiance of the Constitution, federal law, andthis Court's holdings, it is naive to believe the Government will treat this Court's opinions on those policies as "de facto" universal injunctions absent an express order directing total nonenforcement. Ante, at 6 (opinion of KAVANAUGH, J.).

I don't think any of these statements were necessary to rule that universal injunctions were impermissible. These statements of judicial supremacy are regrettable.

Justice Scalia closed his Noel Canning concurrence with this admonition:

We should therefore take every opportunity to affirm the primacy of the Constitution's enduring principles over the politics of the moment. Our failure to do so today will resonate well beyond the particular dispute at hand. Sad, but true: The Court's embrace of the adverse-possession theory of executive power (a characterization the majority resists but does not refute) will be cited in diverse contexts, including those presently unimagined, and will have the effect of aggrandizing the Presidency beyond its constitutional bounds and undermining respect for the separation of powers.

I could say the same thing about CASA, changing "aggrandizing the Presidency" to "aggrandizing the Supreme Court."

9th Circuit Revives Challenge to Community College "Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility" Requirements for Teaching and Other Professional Work

Here's a short excerpt from the Nov. 2023 Report and Recommendations by Magistrate Judge Christopher D. Baker (E.D. Cal.) in Johnson v. Watkin; the plaintiff is a history professor at Bakersfield College, a California public community college. The opinion is long, so I've excerpted it heavily; read the whole thing for more of the legal analysis, and the interesting and contentious factual backstory. The District Court dismissed the case, holding that plaintiff lacked standing, but just today a Ninth Circuit panel (quoted below) reversed that standing decision as to this issue, so the matter will go back down to the lower court.

Cal. Code of Regs. § 53602(a) ["Advancing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Evaluation and Tenure Review Processes"] requires faculty demonstrate (or progress toward) proficiency in the locally-developed DEIA [diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility] competencies, or those published by the Chancellor for their evaluation, including tenure review. For instance, § 53602(b) provides that "District employees must have or establish proficiency in DEIA-related performance to teach, work, or lead within California community colleges." Similarly, § 53605(a) provides that "Faculty members shall employ teaching, learning, and professional practices that reflect DEIA and anti-racist principles, and in particular, respect for, and acknowledgement of the diverse backgrounds of students and colleagues to improve equitable student outcomes and course completion."

Likewise, § 53605(c) provides that "[s]taff members shall promote and incorporate culturally affirming DEIA and anti-racist principles to nurture and create a respectful, inclusive, and equitable learning and work environment." [Defendant California Community College Chancellor Sonia Christian's] characterization of these regulations as merely "articulat[ing] the aspirational goal" of promoting DEIA is disingenuous—by their plain language, the regulations require faculty members like Plaintiff to express a particular message.

The Supreme Court "[has] held time and time again that freedom of speech 'includes both the right to speak freely and the right to refrain from speaking at all.'" Moreover, compelling individuals to mouth support for views they find objectionable, like the government's preferred message, violates the "cardinal constitutional command" that "'no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'"

CASA, Grupo Mexicano, and Ex Parte Young

Does Ex Parte Young find an "Analogue in the Relief Exercised in the English Court of Chancery"?

One of the challenges with Trump v. CASA is accounting for nearly a century worth of Supreme Court decisions. There are a host of landmark decisions where the Court arguably approved of universal injunctions, such as Pierce v. Society of Sisters and West Virginia v. Barnette. Mili Sohoni says these were universal injunctions. Mike Morley disputes these accounts. Justice Barrett discounts these "drive-by" remedial rulings as modern cases that postdate the Judiciary Act of 1789 by more than a century. Justice Sotomayor also cites Brown v. Board of Education II, which proposed some very unusual equitable remedies with "all deliberate speed." Barrett does not respond to Brown. The harder case, in my view, would have been the equitable remedy for Bolling v. Sharpe against the federal government.

But one case where the majority and dissent do engage each other is Ex Parte Young, the classic FedCourts case.

Justice Sotomayor argues that Young is evidence that equitable jurisdiction is not trapped in amber, but instead evolves over time:

Indeed, equitable relief in the United States has evolved in one respect to protect rights and redress wrongs that even the majority does not question: Plaintiffs today may obtain plaintiff-protective injunctions against Government officials that block the enforcement of unconstitutional laws, relief exemplified by Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908). That remedy, which traces back to the equity practice of mid-19th century courts, finds no analogue in the relief exercised in the English Court of Chancery, which could not enjoin the Crown or English officers. See supra, at 24, n. 4; see also Sohoni, 133 Harv. L. Rev., at 928, 1002–1006; see also R. Fallon, D. Meltzer, & D. Shapiro, Hart and Wechsler's The Federal Courts and the Federal System958–959 (5th ed. 2003) (noting that, in Young, "the threatened conduct of the defendant would not have been an actionable wrong at common law" and that the "principle [in Young] has been easily absorbed in suits challenging federal official action"). Under the majority's rigid historical test, however, even plaintiff-protective injunctions against patently unlawful Government action should be impermissible.

Justice Barrett responds to Justice Sotomayor in a footnote:

Notwithstanding Grupo Mexicano, the principal dissent invokes Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908), as support for the proposition that equity can encompass remedies that have "no analogue in the relief exercised in the English Court of Chancery," because Ex parte Young permits plaintiffs to "obtain plaintiff-protective injunctions against Government officials," and the English Court of Chancery "could not enjoin theCrown or English officers," post, at 30 (opinion of SOTOMAYOR, J.). But contrary to the principal dissent's suggestion, Ex parte Young does not say—either explicitly or implicitly—that courts may devise novel remedies that have no background in traditional equitable practice. Historically, a court of equity could issue an antisuit injunction to prevent an officer from engaging in tortious conduct. Ex parte Young justifies its holding by reference to a long line of cases authorizing suits against state officials in certain circumstances. See 209 U. S., at 150–152 (citing, e.g., Osborn v. Bank of United States, 9 Wheat. 738 (1824); Governor of Georgia v. Madrazo, 1 Pet. 110 (1828); and Davis v. Gray, 16 Wall. 203 (1873)). Support for the principal dissent's approach is found not in Ex parte Young, but in Justice Ginsburg's partial dissent in Grupo Mexicano, which eschews the governing historical approach in favor of "[a]dynamic equity jurisprudence." 527 U. S., at 337 (opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part).

I think Justice Barrett gets the better of this argument. The basis of equitable jurisdiction in Ex Parte Young was an "antisuit injunction to prevent an officer from engaging in tortious conduct."

Seth Barrett Tillman and I explained this aspect of Young in our article on the Foreign Emoluments Clause litigation:

The posture of Young was, admittedly, complex. The case began when shareholders of the railroad company sued the company and its directors.285 The shareholders wanted the directors to challenge the constitutionality of the state regulations as violations of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.286 At the time, Minnesota Attorney General Edward Young enforced the railroad regulations.287 The shareholders could invoke the equitable jurisdiction of the federal court because they relied on traditional equitable principles and former Equity Rule 94.288 This provision was the precursor to the modern-day Fed. R. Civ. P. 23.1, which governs derivative actions.289 In Young, the shareholders sought to enforce their fiduciary relationship with the directors. This "trust"-like relationship lies at the core of historical equitable jurisdiction. Indeed, in Federalist No. 80, Hamilton listed "trust" as a traditional cause of action, along with "fraud," "accident," and "hardship."290 Therefore, the shareholders could also rely on a traditional equitable cause of action to challenge the regulations. In the English High Court of Chancery, and in early American courts, causes of action existed that would allow private citizens to challenge government regulations of their own property—even where, as here, title was held beneficially. In Young, the government was regulating the railroad company. Such disputes about contested rights and duties involving property (e.g., interpleader) also lie at the core of historical equitable jurisdiction. Specifically, the Young plaintiffs sought to prevent future state action regulating their own property. To accomplish this goal, they invoked the court's equitable jurisdiction to sue their company, its directors, and state officers before those state officers could regulate the plaintiffs' own property through an imminent coercive lawsuit.291 Professors Bamzai and Bray observe that in Young, "equity [was] invoked to protect a proprietary interest." They write that this "equity-property connection helps focus the dispute and prevents equity from pushing aside other areas of law that have their own separate logic, limits, and principles."292

An interference with private property was, and is, tortious conduct. The basis for equitable jurisdiction in Young was premised, as Barrett wrote, on the government's alleged tortious conduct against private property. This sort of suit would have been permitted in 1789 by the English Court of Chancery.

Turning Credit Cards into Comprehensive Financial Surveillance

New laws on interchange fees will transform credit card payments into detailed government-accessible records of every item purchased, including firearms

In 2011 the Obama administration unleashed Operation Choke Point to use informal regulatory pressure on banks to debank the firearms industry, but that plan withered when exposed in congressional hearings. A few years later, the gun prevention lobbies convinced several states to mandate separate merchant category codes (MCCs) for stores that sell firearms; unfortunately for this initiative, the number of states with statutes that (opens in a new tab)forbid special MCCs for such stores far exceeds the number of states that mandate them. Today, the gun prevention movement is receiving an unexpected gift from merchant lobbies who are pushing to embed sophisticated surveillance infrastructure into the basic architecture of electronic commerce. With that architecture in place, the government will be able to track every item purchased with a credit card — firearms and everything else. The surveillance scheme emerges as an unintended consequence of superficially appealing legislation — namely state-level interchange fee laws — which are promoted as being aimed at helping waitresses, waiters, and small mom-and-pop shops.

This post first describes Operation Choke Point, then its replacement by Merchant Category Codes(MCCs) tracking, and finally the new program for comprehensive surveillance of all purchases. The first two matters are described in my Dickinson Law Review article Big Business as Gun Control, and in my recent post summarizing the article. This post is coauthored with Kristian Stout, who is Director of Innovation Policy at the International Center for Law & Economics, a public policy research organization whose "work is dedicated to the memory"of the famous Law and Economics scholars Armen Alchian and Henry G. Manne.

The first state-level interchange fee statute was enacted in Illinois in June 2024. In the state legislatures, based on who's lobbying for what, the battles over interchange bills often appears as credit card companies versus big box stores, with pro-waitress and pro-small business lobbies chiming in to support the big box stores. But this framing ignores the enormous privacy implications for everyone who uses a credit card: namely forcing credit card companies to make records of the items purchased in every transaction.

Federal Court Rules Against Racial Profiling in "Roving" Immigration Enforcement Raids

Racial profiling is a longstanding problem, exacerbated by Trump Administration deportation policies.

On July 11, Federal District Court Judge Maame Ewusi-Mensah Frimpong (Central District, California) issued an important ruling imposing a temporary restraining order racial profiling in "roving" immigrant enforcement raids. Here is her summary of the issues in the case:

On June 6, 2025, federal law enforcement arrived in Los Angeles to participate in what federal officials have described as "the largest Mass Deportation Operation … in History…" The individuals and organizations who have brought this lawsuit argue that this operation had two key features, both of which were unconstitutional: "roving patrols" indiscriminately rounding up numerous individuals without reasonable suspicion and, having done so, denying these individuals access to lawyers who could help them navigate the legal process they found themselves in. On this, the federal government agrees: Roving patrols without reasonable suspicion violate the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution and denying access to lawyers violates the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. What the federal government would have this Court believe—in the face of a mountain of evidence presented in this case—is that none of this is actually happening.

Most of the questions before this Court are fairly simple and non-controversial, and both sides in this case agree on the answers.

• May the federal government conduct immigration enforcement—even large scale immigration enforcement—in Los Angeles? Yes, it may.

• Do all individuals—regardless of immigration status—share in the rights guaranteed by the Fourth and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution? Yes, they do.

• Is it illegal to conduct roving patrols which identify people based upon race alone, aggressively question them, and then detain them without a warrant, without their consent, and without reasonable suspicion that they are without status? Yes, it is.

• Is it unlawful to prevent people from having access to lawyers who can help them in immigration court? Yes, it is.

There are really two questions in controversy that this Court must decide today.

First, are the individuals and organizations who brought this lawsuit likely to succeed in proving that the federal government is indeed conducting roving patrols without reasonable suspicion and denying access to lawyers? This Court decides—based on all the evidence presented—that they are.

And second, what should be done about it? The individuals and organizations who have brought this lawsuit have made a fairly modest request: that this Court order the federal government to stop.

For the reasons stated below, the Court grants their request.

Interestingly, the Trump Administration, in this case, did not argue that their use of racial profiling is legal, but rather denied it was doing it. As Judge Frimpong explains, that denial goes against "a mountain of evidence" indicating people are being detained and denied access to counsel largely because they are or appear to be Hispanic, speak Spanish, or the like.

This case has been appealed, and there are complex procedural issues, such as the appropriate scope of the TRO. But Judge Frimpong is surely right about the basic point that extensive racial profiling has occurred, and is unconstitutional.

I should, perhaps, note that in this post, I don't try to distinguish between discrimination based on race, and that based on ethnicity (e.g. - Hispanics are more the latter than the former). The law treats these two types of discrimination the same, and there is no good moral reason to distinguish between, either. And, as a practical matter, the two often overlap, as ethnic discrimination and profiling often targets people based in part on "racial" appearance (e.g., in this case, people who look like they are Hispanic).

Racial profiling by law enforcement is a longstanding problem, one not limited to immigration enforcement. Survey data and other evidence indicates that a large majority of Black American males, and also many Black women, and Hispanics, have been victims of profiling at one time or another.

Racial profiling in immigration enforcement is particularly egregious, because it is the one area where racial discrimination is officially approved government policy, at least within so-called "border" areas, which actually encompass places where over two-thirds of the population of the United States lives. In 2014, the Obama Administration considered banning racial profiling in immigration enforcement, but - wrongly - chose not to. They made a terrible mistake, which I criticized at the time.

While the problem isn't new, it has - as the egregious facts of this case show - become worse under the second Trump Administration, with their efforts to impose daily detention quotas, and massively increase deportation, putting pressure on ICE and other agencies to deport as many people as possible. That has predictably led to an upsurge of indiscriminate arrests, most of them targeting people who have never committed any crimes, and many who are present in the US legally or even US citizens. It also, obviously, incentivizes further use of crude shortcuts, including racial profiling.

I have, for many years, argued that racial profiling is unconstitutional, and urged people - including conservatives and my fellow libertarians - to take the issue more seriously, and give it a high priority (see, e.g., here, here, and here). I summarized some of the reasons why in a 2022 post:

In previous posts, I have explained why racial profiling in immigration enforcement is harmful and unjust, and also why racial profiling is a great evil more generally, and unconstitutional, to boot. Progressives, conservatives, and libertarians all have good reason to condemn the practice.

If you're a conservative - or anyone else - committed to color-blindness in government policy (a commitment I share), you cannot make an exception for law enforcement...

If you truly believe that it is wrong for government to discriminate on the basis of race, you cannot ignore that principle when it comes to those government officials who carry badges and guns and have the power to kill and injure people. Otherwise, your position is blatantly inconsistent. Cynics will understandably suspect that your supposed opposition to discrimination only arise when whites are the victims, as in the case of affirmative action preferences in education.

I don't think I need to explain in detail why libertarians should be opposed to racial profiling in immigration enforcement, or law enforcement more generally. All our usual concerns about law enforcement abuses become even more pressing when racial discrimination enters the mix - especially if that discrimination is openly condoned by policy. And, of course, libertarians are no fans of immigration restrictions generally.

Finally, if you're a progressive, and you believe ending racial discrimination in the criminal justice system is an important priority, you cannot make an exception for immigration enforcement in so-called "border" areas [as the Obama Administration did] that actually encompass areas where the vast majority of Americans live. You especially should not do so, given the long history of racial and ethnic bias in immigration policy.

When it comes to immigration enforcement, there is a deeper problem arising from the fact that most immigration restrictions inherently restrict people's liberty based on morally arbitrary circumstances of ancestry and place of birth. For that reason, they are unjust for much the same reasons as racial discrimination is unjust - even in cases where the exclusionary policies in question are not explicitly based on race or ethnicity.

Current law and Supreme Court precedent doesn't allow a quick and easy solution to that problem, though the ultimate long-term solution is to overturn the awful Chinese Exclusion Case, which wrongly held that the federal government has a general power to bar immigration, even though no such power is enumerated anywhere in the Constitution. I describe some possible ways to do that in this article.

That probably won't happen anytime soon. In the meantime, however, there is much all three branches of government can do to curb racial profiling, in both immigration policy, and other aspects of law enforcement.

Bruen and CASA: Analogical Originalism

Yet, neither the majority nor the dissent cited Bruen

I've finally finished Trump v. CASA. And I have lots of thoughts. But for starters, I wanted to focus on an obvious missing link between CASA and Bruen.

In Grupo Mexicano, Justice Scalia used reasoning by analogy to determine whether a particular remedy is within the scope of the equitable jurisdiction of federal courts:

We must therefore ask whether universal injunctions are sufficiently "analogous" to the relief issued "'by the HighCourt of Chancery in England at the time of the adoption of the Constitution and the enactment of the original Judiciary Act.'" Grupo Mexicano, 527 U. S., at 318–319 (quoting A. Dobie, Handbook of Federal Jurisdiction and Procedure 660 (1928)).

The answer is no: Neither the universal injunction nor any analogous form of relief was available in the High Court of Chancery in England at the time of the founding. . . .

Under Grupo Mexicano de Desarrollo, S. A. v. Alliance Bond Fund, Inc., 527 U. S. 308 (1999), the lack of a historical analogue is dispositive.

Sound familiar? In Bruen, Justice Thomas followed a similar originalist framework to determine if a particular gun-control law aws within the scope of the government's regulatory power:

Much like we use history to determine which modern "arms" are protected by the Second Amendment, so too does history guide our consideration of modern regulations that were unimaginable at the founding. When confronting such present-day firearm regulations, this historical inquiry that courts must conduct will often involve reasoning by analogy—a commonplace task for any lawyer or judge. Like all analogical reasoning, determining whether a historical regulation is a proper analogue for a distinctly modern firearm regulation requires a determination of whether the two regulations are "relevantly similar."

One would think that Bruen would at least get a See also citation here. But nothing.

There's more. In CASA, Justice Sotomayor's dissent accused the majority of freezing equity in "amber":

Most critically, the majority fundamentally misunderstands the nature of equity by freezing in amber the preciseremedies available at the time of the Judiciary Act.

Justice Barrett responds:

A modern device need not have an exact historical match, but under Grupo Mexicano, it must have a founding-era antecedent. And neither the universal injunction nor a sufficiently comparable predecessor was available from a court of equity at the time of our country's inception

Sound familiar? Chief Justice Roberts in Rahimi wrote that the Second Amendment is not trapped in amber.

Nevertheless, some courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases. These precedents were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber.

And Sotomayor quoted the Chief in her Rahimi concurrence:

Thankfully, the Court rejects that rigid approach to the historical inquiry. As the Court puts it today, Bruen was "not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber."

As did Justice Jackson:

The Court today expounds on the history-and-tradition inquiry that Bruen requires. . . . Ante, at 7–8. We emphasize that the Second Amendment is "not … a law trapped in amber."

Justice Barrett also embraced the line:

To be consistent with historical limits, a challenged regulation need not be an updated model of a historical counterpart. Besides, imposing a test that demands overly specific analogues has serious problems. To name two: It forces 21st-century regulations to follow late-18th-century policy choices, giving us "a law trapped in amber."

Justice Gorsuch's concurrence seemed content to be bound by amber, but doesn't think there is amber here:

We have no authority to question that judgment. As judges charged with respecting the people's directions in the Constitution—directions that are "trapped in amber," see ante, at 7—our only lawful role is to apply them in the cases that come before us. Developments in the world may change, facts on the ground may evolve, and new laws may invite new challenges, but the Constitution the people adopted remains our enduring guide.

How is it possible that the CASA majority and dissent talked about law being trapped in amber, but there was no mention of this line from Rahimi.

There's still more. Justice Sotomayor's dissent cites several injunctions from the twentieth century that she claims were universal. Justice Barrett's majority opinion discounts the relevance of these modern injunctions:

Regardless, under any account, universal injunctions postdated the founding by more than a century—and under Grupo Mexicano, equitable authority exercised under the Judiciary Act must derive from founding-era practice. 527 U. S., at 319.

To be clear, Barrett is not discussing the original meaning of Article III. The Court quite consciously did not address that issue. Rather, Barrett is trying to determine the original meaning of equitable jurisdiction under the Judiciary Act of 1789. And the framework there is more-or-less the same. Indeed, I think debates by the First Congress help inform the original meaning of Article III.

Where have we heard Justice Barrett writing that we should not consider post-enactment history? Her Bruen and Rahimi concurrences. She criticized the majority for considering gun control laws from after the framing. But there is again no mention of Bruen.

I should note that Jack Goldsmith writes that Barrett erred on her "temporal focus." The relevant timeframe, Jack writes, is 1875 when the precursor to Section 1331 was enacted. Sam Bray responds that 1787 is the correct time frame. I'm not sure who is right here, but I agree with Jack and Sam that this distinction likely is without a difference as universal injunctions were creatures of the twentieth century

In any event, it's like the Court pretends that entire Bruen/Rahimi (Brahimi?) episode never happened.

Can American Citizens Lose Their Citizenship?

Yes, but only if they intend to relinquish it (or, if they are naturalized citizens and committed fraud during the naturalization process).

Let's begin with the constitutional text, here from section 1 of the 14th Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Once you have American citizenship, you have a constitutional entitlement to it. If you like your American citizenship, you can keep your American citizenship—and that's with the Supreme Court's guarantee, see Afroyim v. Rusk (1967):

There is no indication in these words of a fleeting citizenship, good at the moment it is acquired but subject to destruction by the Government at any time. Rather the Amendment can most reasonably be read as defining a citizenship which a citizen keeps unless he voluntarily relinquishes it. Once acquired, this Fourteenth Amendment citizenship was not to be shifted, canceled, or diluted at the will of the Federal Government, the States, or any other governmental unit.

(Special bonus in Afroyim: a cameo appearance by a Representative Van Trump in 1868, who said, among other things, "To enforce expatriation or exile against a citizen without his consent is not a power anywhere belonging to this Government. No conservative-minded statesman, no intelligent legislator, no sound lawyer has ever maintained any such power in any branch of the Government.") In Vance v. Terrazas (1980), all the justices agreed with this principle.

Now, as with almost all things in law—and in life—there are some twists. Naturalized citizens can lose their citizenship if they procured their citizenship by lying on their citizenship applications; the premise there is that legal rights have traditionally been voided by fraud in procuring those rights. And citizens can voluntarily surrender their citizenship, just as people can generally waive many of their legal rights. This surrender can sometimes be inferred from conduct (such as voluntary service in an enemy nation's army), if the government can show that the conduct was engaged in with the intent to surrender citizenship. The relevant federal statute, 8 U.S. Code § 1481, provides (emphasis added):

Congratulations to Our Own David Bernstein, Josh Blackman, and Todd Zywicki!

I'm delighted to report that David and Josh are among the recipients of the Heritage Foundation's 2025 Freedom and Opportunity Academic Prize, and that Todd won it last year. Many other academics in various fields (law, economics, history, philosophy, political science, and more) also received the prizes.

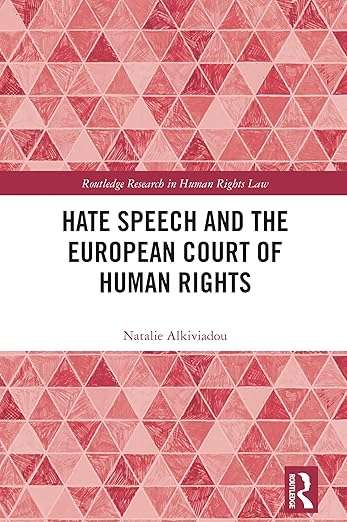

Natalie Alkiviadou Guest-Blogging About "Hate Speech and the European Court of Human Rights"

I'm delighted to report that Dr. Natalie Alkiviadou, Senior Research Fellow at the Future of Free Speech at Vanderbilt University will be guest-blogging this week about this new book of hers. Here is a summary of the book, from the publisher:

This book argues that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) should reconsider its approach to hate speech cases and develop a robust protection of freedom of expression as set out in the benchmark case of Handyside v the United Kingdom. In that case, the ECtHR determined that Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), safeguarding the right to freedom of expression, extends protection not only to opinions which are well received but also to those deemed offensive, shocking, or disturbing. However, subsequent rulings by the Court have generated a significant amount of contradictory case law.

Against this backdrop, this book provides an analysis of hate speech case law before the ECtHR and the now-obsolete European Commission on Human Rights. Through a jurisprudential analysis, it is argued that these institutions have adopted an overly restrictive approach to hate speech, which fails to provide adequate protection of the right to freedom of expression. It also demonstrates that there are stark inconsistencies when it comes to the treatment of some forms of 'hate speech' versus others.

Skrmetti, Mahmoud, and Free Speech Coalition - "Won't Somebody Please Think of the Children?"

I think Skrmetti, Mahmoud, and Free Speech Coalition can be summed up in a meme: Won't somebody please think of the Children? But more precisely, the Court was protecting children from misguided parents.

In Free Speech Coalition, the Court allowed the state to protect children from accessing pornography that their parents might wish to access. In Skrmetti, the Court allowed the state to protect children whose parents approved puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. And in Mahmoud, the Court allowed parents to protect their children from the school board.

These three cases are not the same, but at bottom, they were all about protecting the children.

Free Speech Coalition Brings Text, History, and Tradition to the Free Speech Clause

Justice Thomas tries to Bruenify free speech doctrine, but I'm not sure it will work.

I have now finished reading Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton. This 6-3 decision upheld Texas's age-verification law to access pornographic materials online. Justice Thomas wrote the majority opinion and Justice Kagan wrote the dissent.

In many regards, this case is confounding. I think the Texas law is constitutional under any standard of review--rational basis, intermediate scrutiny, or strict scrutiny. And I think that Justice Kagan likely agrees on that point, though I doubt that her two colleagues would uphold the law under strict scrutiny. The only debate concerns the appropriate standard of review. I think the Fifth Circuit rightly found that this law is best reviewed with rational basis scrutiny. And I suspect that Justice Thomas agrees with the Fifth Circuit. Indeed, the first half of his opinion sounds as if the law will be reviewed deferentially.

Yet, the majority ultimately applies intermediate scrutiny, under something like the O'Brien test. Thomas probably needed to go down this path to hold five votes. On this point, I find myself in agreement with Justice Kagan. O'Brien seems like a very bad fit for the sort of law at issue. O'Brien is about conduct with speech elements. The Texas law does not implicate any conduct. Indeed, while I usually celebrate Justice Thomas's opinions, Paxton was not his finest moment. This is an area where Justice Kagan clearly has more expertise, and she shows it. Then-Professor Kagan did not write very much (sound familiar?), but she was a well-regarded expert on First Amendment law.

So what is going on here? Justice Thomas was trying to reorient Free Speech doctrine around text, history, and tradition. Or, Justice Thomas tried to Bruenify free speech doctrine, but I'm not sure it will work.

In Bruen, Thomas argued that Second Amendment claims are not reviewed with means-end scrutiny. And, Thomas claimed that this "Second Amendment standard accords with how we protect other constitutional rights," including the First Amendment. Specifically, for the government to meet its burden to restrict speech, it "must generally point to historical evidence about the reach of the First Amendment's protections." When I first read Bruen, I scratched my head with this sentence. Free Speech doctrine is a doctrinal mess. The Court has employed a series of different means-ends balancing test. Originalism is not really relevant to the the Free Speech clause.

In Free Speech Coalition, Justice Thomas, like in Bruen, was trying to ground the doctrine in text, history and tradition. At least with the Second Amendment, there was not much caselaw to apply. Heller was decided in what I've described as an "open field." But the Free Speech Clause is a thorny ticket with so much caselaw. I suppose that the fact that five members joined Thomas's opinion suggests that the Court is comfortable with changing course on Free Speech law. Then again, five members joined his Bruen opinion and jumped ship at an entirely predictable moment.

I blame Chief Justice Roberts (who else?). He should not have given this opinion to Justice Thomas. Indeed, for reasons that are unclear, Thomas took a shot at Roberts's majority opinion isn Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar:

In Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar, 575 U. S. 433 (2015), a bare majority held that a ban on the personal solicitation of campaign donations by candidates for judicial office survived strict scrutiny. But, only four Members of the majority thought that the statute triggered strict scrutiny to begin with.

Thomas has a hard time holding together a majority opinion on a difficult case. When he was given the Bruen majority, the Court had to clean it up barely a year later in Rahimi. I would have assigned this opinion to Justice Barrett or Justice Alito or really anyone else. Hell, Roberts could have assigned Kagan the majority opinion, to uphold this law under strict scrutiny, with Thomas and Alito concurring to say rational basis review should apply. I can imagine how much finessing this majority opinion took to cross the finish line. Roberts probably would take this one back.

So (at least for now) what is Thomas's approach: use history to determine what is the appropriate standard of review. If there is some long-standing, "traditional" prohibition, the Court should presume it is constitutional; and given that strict scrutiny is usually fatal, that sort of prohibition must be subject to a more deferential standard of review. States have long imposed some sort of age-verification system on pornography, so these sorts of law are not subject to strict scrutiny.

Here are all the ways that Justice Thomas refers to "tradition":

And petitioners concede that an in-person age verification requirement is a "traditional sort of law" that is "almost surely" constitutional. Tr. of Oral Arg. 17.

H. B. 1181 thus falls within Texas's traditional power to protect minors from speech that is obscene from their perspective.

Strict scrutiny therefore cannot apply to laws, such as in-person age-verification requirements, which are traditional, widespread, and not thought to raise a significant First Amendment issue.

Petitioners would like to invalidate H. B. 1181 without upsetting traditional in-person age-verification requirements and perhaps narrower online requirements. But, strict scrutiny is ill suited for such nuanced work. The only principled way to give due consideration to both the FirstAmendment and States' legitimate interests in protecting minors is to employ a less exacting standard.

Thomas also tries to bring some sort of means-ends balancing into the historical component. He speaks of "ordinary and appropriate means." That is sort-of like "necessary and proper"?

Instead, as we have explained, the First Amendment leaves undisturbed States' power to impose age limits on speech that is obscene to minors. That power, according to both "common sense" and centuries of legal tradition, includes the ordinary and appropriate means of exercising it.Scalia & Garner, Reading Law, at 192. And, an age-verification requirement is an ordinary and appropriate means of enforcing an age limit, as is evident both from all other contexts where the law draws lines based on age and from the long, widespread, and unchallenged practice of requiring age verification for in-person sales of material that is obscene to minors.

Justice Kagan, in dissent, expresses bewilderment about this approach.

The majority's opinion concluding to the contrary is, to be frank, confused. The opinion, to start with, is at war with itself.

See, I got in trouble for calling a Supreme Court justice "confused."

Kagan continues:

The usual way constitutional review works is to figure out the right standard (here, strict scrutiny because H. B. 1181 is content-based), and let that standard work to a conclusion. It is not to assume the conclusion (approve H. B. 1181 and similar age verification laws) and pick the standard sure to arrive there. But that is what the majority does. To answer what standard of scrutiny applies, the majority first spends four pages lauding age verification schemes as "common," "traditional,""appropriate," and "necessary." Ante, at 13–18. In other words, all over the place, and a good thing too. No wonder the majority doesn't land on strict scrutiny.

Kagan writes that the majority's approach seems backwards:

The analytic path of today's opinion is winding, but I take the majority to begin with a conviction about where it must not end—with strict scrutiny. The majority is not so coy about this backwards reasoning. To the contrary, it defends it.

Thomas sort of acknowledges the criticism:

Finally, the dissent claims that we engage in "backwards," results-oriented reasoning because we are unwilling to adopt a position that would call into question the constitutionality of longstanding in-person age-verification requirements. Not so. We appeal to these requirements because they embody a constitutional judgment—made by generations of legislators and by the American people as a whole—that commands our respect. A decision "contrary to long and unchallenged practice . . . should be approached with great caution," "no less than an explicit overruling" of a precedent. Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U. S. 808, 835 (1991) (Scalia, J., concurring). It would be perverse if we showed less regard for in-person age-verification requirements simply because their legitimacy is so uncontroversial that the need for a judicial decision upholding them has never arisen.

I think this is a Kavanaugh-like mode of reasoning about tradition. But I'm not entirely sure how it maps on the First Amendment. I think Thomas would determine the level of scrutiny based on tradition. This wasn't the Court's approach before. But it, apparently, is the approach now. Or at least until the Court walks it back.

I do have to commend Justice Kagan's dissent. This is vintage Kagan. It has all of her usual witticisms, combined with a deep knowledge of the subject matter. It was a bit of a breath of fresh air, as this last term has not been her best. She simply didn't write that much, and what she wrote was not really memorable. Moreover, her questions from the bench were not as tight as they had been in the past. I sense she is frustrated and perhaps annoyed at where the Court is. I also sense some discord with her progressive colleague. For example, it would have made so much sense for Justice Kagan to write the principal dissent in Casa. The former federal courts and procedure professor would have been uniquely suited to respond to another former federal courts and procedure professor. But instead, we got Justice Sotomayor.

Donald Trump, The Transformational President

The New York Times admits that Trump is going further than Buckley, Reagan, Goldwater, and Taft "might have imagined possible"

Today the New York Times published a "news analysis" titled "From Science to Diversity, Trump Hits the Reverse Button on Decades of Change." For those who do not read the Times--and I don't blame you--a "news analysis" is where a reporter writes an op-ed. It is not entirely objective, but instead allows a card-carrying journalist to tell us what he really thinks. Yet, if you read between the lines, you can actually see some admiration: Trump is doing what was once thought impossible. Consider this excerpt:

Mr. Trump's shift into reverse gear reflects the broader sentiments of many Americans eager for a change in course. The United States has cycled from progressive to conservative eras throughout its history. The liberal period ushered in by Franklin D. Roosevelt eventually led to a swing back to the right under Ronald Reagan, which led to a move toward the center under Bill Clinton.

But Mr. Trump has supercharged the current swing. The influential writer William F. Buckley Jr. once defined a conservative as someone standing athwart history and yelling, "Stop!" Mr. Trump seems to be standing athwart history yelling, "Go back!"

He has gone further than noted conservatives like Mr. Buckley, Mr. Reagan, Barry Goldwater or Robert Taft might have imagined possible. While they despised many of the New Deal and Great Society programs that liberal presidents introduced over the years, and sought to limit them, they recognized the futility of unraveling them altogether.

"They were living in an era dominated by liberals," said Sam Tanenhaus, author of "Buckley," a biography published last month. "The best they could hope for was to arrest, 'stop,' liberal progress. But what they dreamed of was a counterrevolution that would restore the country to an early time — the Gilded Age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries."

"Trump," he added, "has outdone them all, because he understands liberalism is in retreat. He has pushed beyond Buckley's 'stop,' and instead promises a full-throttle reversal."

Indeed, although Mr. Reagan vowed during his 1980 campaign to abolish the Department of Education, which had been created the year before over the objections of conservatives who considered it an intrusion on local control over schools, he never really tried to follow through as president, because Democrats controlled the House. The issue largely faded until Mr. Trump this year resurrected it and, unlike Mr. Reagan, simply ignored Congress to unilaterally order the department shuttered.

One of Trump's greatest strengths is his ability to not care what elites think. Usually, when the elites calls a conservative a racist or sexist or homophobe or something else, he wilts. When they accuse a conservative of trying to hurt poor people or roll back progress, he caves. When they charge a conservative with standing on the wrong side of the arc of history, he switches sides. Not Trump. He can almost single-handedly shift the Overton window on what topics are open for discussion. And Trump inspires other conservatives to likewise discount what elites think. That mantra has spread.

Things that have been accomplished would have been unfathomable a decade ago. Let's just rattle off a few high points. Roe v. Wade is gone. Humphrey's Executor is on life support. Even after Obergefell and Bostock, we got Skrmetti. Despite all the outrage, illegal immigration at the southern border has basically trickled to a halt. Blind deference to "experts" has been irreparably altered by the distrust occasioned by COVID and transgender medicine for children. The federal bureaucracy is being dismantled. Nationwide injunctions are no more. And so on.

A common refrain is that Trump is ignoring the Constitution. During the New Deal and the Great Society, FDR and LBJ did great violence to the Constitution and the separation of powers. They got away with it because they were trying to do the "right" thing. Yet critics expect Trump to behave nicely, and be a good conservative like George W. Bush or Mitt Romney. That's not what we have. And in Trump's defense, some (but not all) of his actions are seeking to restore the original meaning of the Constitution, whereas the same could not be said for FDR and LBJ.

Speaking of book projects, I am in the early stages of a three-volume set on the Trump presidency and the Constitution. I actually wrote most of the first installment by the end of 2020, but put it on hold after January 6. I had no idea what the future would bring, so I stood down. I think the first installment would track from the moment Trump came down the golden escalator to election day in 2020. The second installment would start with the 2020 election, cover January 6, and chronicle the three years of Lawfare (Jack Smith, Section 3, and everything else). The third installment would begin on inauguration day 2025, through… Well, I'm not really sure where this all ends. But it is clear enough to me that Trump has transformed the nation in ways that likely cannot just be forgotten come 2029.

Constitutional Law, in Pop Culture

A funny movie from my youth was Tommy Boy, starring Chris Farley and David Spade. I recently rewatched it. This question on Chris Farley's final exam in history made me cringe (and not because he wrote Herbie Hancock).

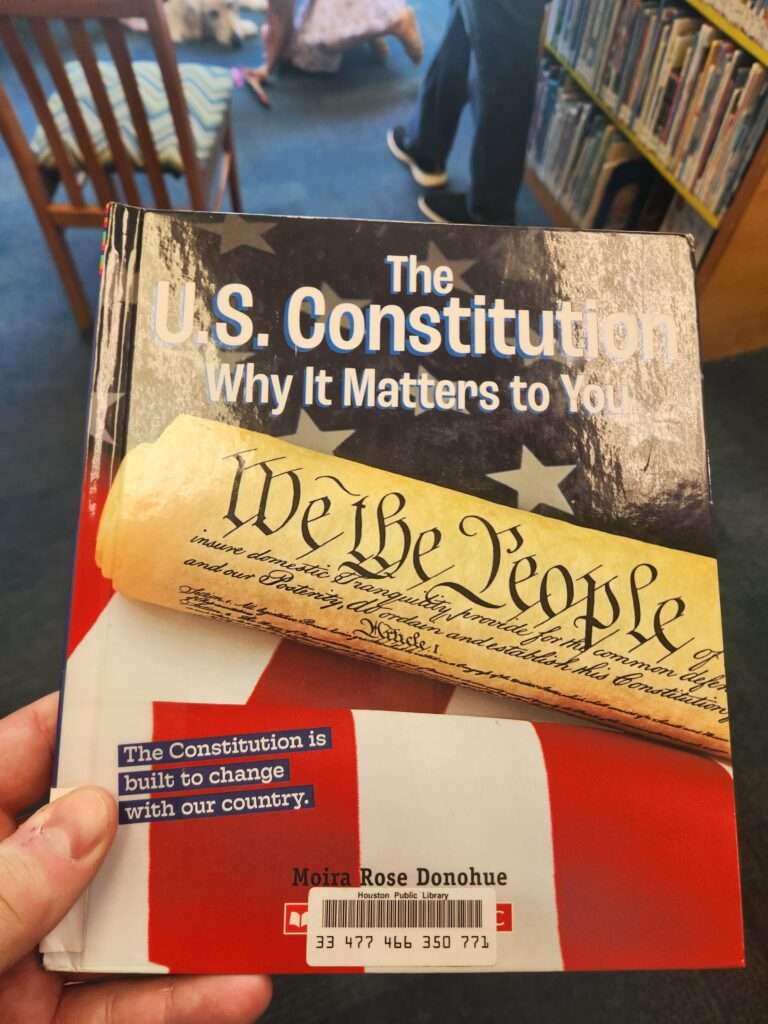

Then again, perhaps I should let the producers off easy. I recently saw this book at the Houston Public Library, and also cringed.

No, the Constitution is not built to change with our country. It was made notoriously difficult to amend. This author has no apparent expertise about the Constitution, but I suppose that shouldn't stop her from writing about it.

One of my long-term goals is to write children books about the Constitution. It's on the agenda.

Show Comments (570)