A Prosecutor Allegedly Tried To Jail Him for Fighting Civil Forfeiture. He May Finally Get His Day in Court.

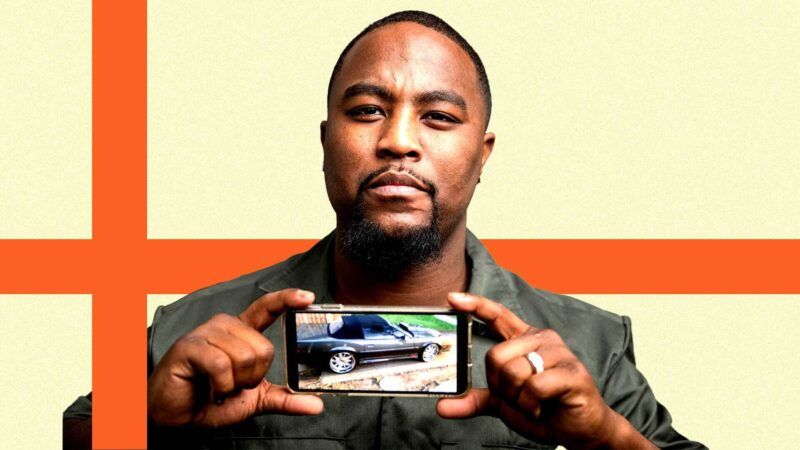

Law enforcement seized Robert Reeves' Chevrolet Camaro without charging him with a crime. After he filed a class-action lawsuit, that changed.

A prosecutor who allegedly weaponized the criminal code to retaliate against a man for filing a class-action lawsuit that challenged the notorious civil forfeiture program in Wayne County, Michigan, is not entitled to prosecutorial immunity, a state appeals court ruled Monday, sending the man's lawsuit against that prosecutor back to the trial court.

It is a significant legal victory when considering that such claims are often dead on arrival.

Police seized Robert Reeves' Chevrolet Camaro and $2,000 in cash in 2019 on suspicion that he had stolen a skid steer from Home Depot. But as Reason's C.J. Ciaramella wrote in 2023, Reeves was not arrested or charged with a crime, and he was not able to actually challenge the seizure of his vehicle, as the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office (WCPO) declined to file a notice of intent to forfeit it.

About seven months later, Reeves joined the class-action suit, filed by the Institute for Justice, a public-interest law firm, which alleged that Wayne County's civil forfeiture program violated the Constitution in multiple ways. Prosecutors responded expeditiously. First, the WCPO wrote the next day to a state police task force instructing it to release Reeves' car and his cash. Then, two weeks later, prosecutors filed felony charges against Reeves for allegedly receiving and concealing stolen property. Perhaps most notably, the government asked a judge to suspend his lawsuit while the criminal case against him proceeded, and Wayne County's Department of Corporation Counsel (DCC) used the charges as a defense against the suit.

A judge would dismiss those charges for lack of evidence—in February 2021, over a year later, in part after delays brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Prosecutors were undeterred. They refiled the same charges shortly after that dismissal, only for them to again be dismissed for lack of evidence, this time in January 2022.

Reeves then sued, alleging those criminal prosecutions violated his First and 14th Amendment rights as part of a concerted effort to derail his complaint against the county's civil forfeiture program—the practice that allows law enforcement to seize people's property even if they have not charged, much less convicted, the owner of a crime.

"The pending charges caused Robert to be disqualified for expungement of prior offenses at a free expungement clinic, to spend time imprisoned in a COVID-infested jail, and to lose at least one job, when a police-officer client refused to allow [Reeves] to work as a contractor at his home specifically because of the pending charges," his complaint says. "Defendants' retaliatory prosecutions against [Reeves] were motivated by [Reeves'] participation in a federal class action lawsuit against Wayne County—protected activity under the First and Fourteenth Amendments."

His complaint also notes that the "defendants worked together across departments—with the WCPO taking advice and direction from the DCC—in an irregular effort to pursue the criminal prosecutions."

Suits like Reeves' are usually doomed before they begin, as prosecutors are protected by absolute immunity for judicial or quasi-judicial functions. In practice, that means victims have no recourse against district attorneys who may falsify evidence, introduce perjured testimony, coerce witnesses, or hide exculpatory information from the defense.

But the State of Michigan Court of Appeals reversed a trial court decision and ruled yesterday that Dennis Doherty, the prosecutor who allegedly retaliated against Reeves by bringing felony charges, was not entitled to that protection, because the alleged misconduct did not qualify as quasi-judicial.

"[Reeves] alleged that Doherty contacted the new officer in charge of the task force to seek clarification, recommended submission of the warrant request, and directed the officer in charge to file that request," the court wrote. "Those allegations suggest that Doherty's conduct was aimed at reviving a dormant prosecution and falls within the category of investigative or administrative acts, not quasi-judicial ones."

For those acts, prosecutors are entitled to qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that permits civil suits against state and local government officials only if a plaintiff can prove it was already "clearly established" that the misconduct in question was unconstitutional. The trial court will now evaluate that question here.

It's still a very high bar to meet. But in a commentary on how difficult it can be for victims of government abuse to find recourse, Reeves has a glimmer of hope after facing what are typically impossible odds.

Show Comments (15)