Biden's Preemptive Pardons Undermine Official Accountability and the Rule of Law

His last-minute acts of clemency invite Trump and future presidents to shield their underlings from the consequences of committing crimes in office.

Last month, Joe Biden issued a broad pardon for his son Hunter that not only spared him sentencing on gun and tax charges but also barred his prosecution for any federal crimes he might have committed from January 1, 2014, through December 1, 2024. On his way out the door today, Biden granted similarly sweeping pardons to Gen. Mark Milley, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and all nine members of the House select committee that investigated the January 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol, plus the committee's staff and Capitol Police officers who testified before it. He also issued preemptive pardons for five of his relatives: three siblings, a brother-in-law, and a sister-in-law.

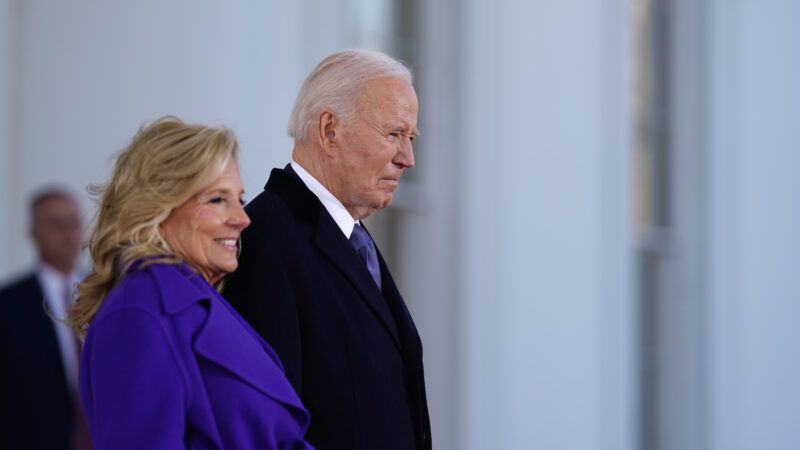

According to Biden, all of these pardons are aimed at preventing President Donald Trump, who took his second oath of office today in the same building that his supporters invaded and vandalized four years ago, from retaliating against his political enemies by launching frivolous criminal investigations. But in seeking to stop Trump from abusing presidential powers, Biden stretched the limits of those powers and set a dangerous precedent that undermines the rule of law and the accountability of federal officials.

Under Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, the president has plenary power to "grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment." In the 1866 case Ex parte Garland, the Supreme Court held that "the power thus conferred is unlimited, with the exception stated." That power, the Court said, "extends to every offence known to the law" and "may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken or during their pendency or after conviction and judgment." Although pardons typically are granted after convictions, in other words, presidents may issue them in cases where no charges have yet been filed, provided the underlying conduct predates the pardon.

The closest historical precedent for Biden's preemptive acts of clemency is the pardon that President Gerald Ford granted to his predecessor, Richard Nixon, a month after taking office. That pardon applied to "all offenses against the United States" that Nixon "has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969, through August 9, 1974." But there are several notable differences between that act of clemency and the pardons for Milley et al.

Nixon resigned to avoid an impeachment that seemed inevitable in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The articles of impeachment that the House Judiciary Committee approved on July 27, 1974, charged Nixon with a litany of offenses, many of which would amount to federal crimes.

The first article alleged that Nixon had violated his oath of office and his presidential responsibilities by engaging in "a course of conduct or plan designed to delay, impede, and obstruct the investigation" of the Watergate burglary. It listed nine examples of such conduct, including "false or misleading statements" to investigators, "withholding relevant and material evidence," encouraging witnesses to make false statements, paying witnesses for their silence, leaking confidential information to people who were under investigation, and offering lenient treatment to defendants "in return for their silence or false testimony." The second article of impeachment charged Nixon with abusing his powers in various other ways, such as deploying the IRS, the FBI, the CIA, and the Secret Service against political opponents.

Ford's pardon acknowledged that Nixon, "as a result of certain acts or omissions occurring before his resignation," had "become liable to possible indictment and trial for offenses against the United States." Ford worried that "the tranquility to which this nation has been restored by the events of recent weeks could be irreparably lost by the prospects of bringing to trial a former President of the United States." Nixon's prosecution, Ford said, would "cause prolonged and divisive debate over the propriety of exposing to further punishment and degradation a man who has already paid the unprecedented penalty of relinquishing the highest elective office of the United States."

Ford, in other words, conceded that Nixon might be successfully prosecuted for various federal crimes. But because that process would incite bitter discord and disturb the "tranquility" that followed Nixon's resignation, Ford thought, it was best to stop it before it started.

In the case of Milley, Fauci, and the January 6 committee members, by contrast, Biden cautioned that "the issuance of these pardons should not be mistaken as an acknowledgment that any individual engaged in any wrongdoing, nor should acceptance be misconstrued as an admission of guilt for any offense." To the contrary, he said, the pardons were necessary because the recipients "have been subjected to ongoing threats and intimidation for faithfully discharging their duties." Milley, Fauci, and the committee members "have served our nation with honor and distinction," Biden declared, "and do not deserve to be the targets of unjustified and politically motivated prosecutions."

Biden offered a similar explanation for pardoning his relatives. "My family has been subjected to unrelenting attacks and threats, motivated solely by a desire to hurt me — the worst kind of partisan politics," he said. "Unfortunately, I have no reason to believe these attacks will end."

Even if such attacks are ultimately unsuccessful, Biden noted, the process itself exacts a price. "I believe in the rule of law, and I am optimistic that the strength of our legal institutions will ultimately prevail over politics," he said. "But these are exceptional circumstances, and I cannot in good conscience do nothing. Baseless and politically motivated investigations wreak havoc on the lives, safety, and financial security of targeted individuals and their families. Even when individuals have done nothing wrong—and in fact have done the right thing—and will ultimately be exonerated, the mere fact of being investigated or prosecuted can irreparably damage reputations and finances."

Notwithstanding those caveats, Trump and his supporters are bound to portray these pardons as admissions of guilt. And even Americans who are not Trump fans are apt to wonder why someone who had done nothing wrong would accept a presidential pardon. "I am guilty of nothing besides bringing the truth to the American people and, in the process, embarrassing Donald Trump," former Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R–Ill.), who served on the January 6 committee, said on CNN a couple of weeks ago. But he noted that "as soon as you take a pardon, it looks like you are guilty of something,"

Sarah Isgur, an attorney who served as a Justice Department spokeswoman during Trump's first term, recognizes that reality. Isgur is one of 60 former executive branch officials who appear on the list of enemies that Kash Patel, Trump's pick to run the FBI, included in his 2023 book Government Gangsters, which alleges a "deep state" conspiracy against Trump that Patel equates with a conspiracy to subvert democracy and the Constitution. Although "I'm on Mr. Patel's list," Isgur wrote in a New York Times essay last month, "I don't want a pardon. I can't speak for anyone else on the list, but I would hope that none of them would want a pardon, either."

Isgur explained why: "If we broke the law, we should be charged and convicted. If we didn't break the law, we should be willing to show that we trust the fairness of the justice system that so many of us have defended. And we shouldn't give permission to future presidents to pardon political allies who may commit real crimes on their behalf."

Milley, a vocal Trump critic who has described his former boss as "fascist to the core," seems to fall into the category of potential targets who "didn't break the law." Trump has said that Milley deserves to be executed for calling his Chinese counterpart in 2020 and 2021 to assure him that rumors of an impending U.S. attack were baseless. "This is an act so egregious that, in times gone by, the punishment would have been DEATH!" Trump wrote on Truth Social in September 2023.

Trump's threats against the members of the January 6 committee likewise seem legally groundless. Trump has argued that former Rep. Liz Cheney (R–Wyo.) and every other member of the committee are guilty of "treason," which is punishable by death or by a prison sentence of at least five years. A person commits that crime when he "ow[es] allegiance to the United States" and "levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere." Even less risible charges would seem to be precluded by the Constitution, which says members of Congress "shall not be questioned in any other place" for "any speech or debate in either house."

Fauci's case is a closer call. Trump allies such as Elon Musk and Sen. Ted Cruz (R–Texas) have argued that Fauci should be prosecuted for lying to Congress about U.S. funding for gain-of-function research on viruses in China.

Fauci "flat-out lied to Congress when he said that, no, the federal government had not funded gain-of-function research at the Wuhan Institute for Virology," Cruz said during a December 2022 interview on Fox News. Although the National Institutes of Health later "made clear that was a lie," Cruz complained, Attorney General Merrick Garland "won't prosecute him." In a July 2021 letter to Garland, Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.) suggested that Fauci had violated 18 USC 1001, which applies to someone who makes "any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation" regarding "any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch." That is a felony punishable by up to five years in prison.

Thanks to Biden's pardon, we will never know if prosecutors could have proven that case beyond a reasonable doubt. Likewise for additional charges that Hunter Biden might have faced in connection with his income taxes or allegations of foreign lobbying. Nor will Trump's vague charges of corruption against "the entire Biden crime family" ever be tested by investigators, prosecutors, judges, or jurors.

If you are confident that there is nothing to any of these claims, you may think that is just as well. But as Isgur notes, the pardon power that Biden has deployed in an unprecedented way could easily become a shield for a president's political allies, including government officials, who "commit real crimes." That prospect should trouble anyone who worries that Trump or any future president might copy Nixon's example by enlisting his underlings to break the law in service of his policy, political, or personal agenda.

"I don't want to see each president hereafter on their way out the door giving a broad category of pardons to members of their administration," Rep. Adam Schiff (D–Calif.), a member of the January 6 committee, said on CNN this month. It is not hard to see why: If presidents get in the habit of preemptively pardoning their underlings, impeachment (resulting in removal and possibly also disqualification from future government service) will be the only real remedy for federal officials who commit crimes, and that option is available only when their abuses come to light soon enough to complete that process. Coupled with the Supreme Court's broad understanding of presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for "official acts," this is a recipe for impunity that belies Biden's avowed commitment to the rule of law.

Show Comments (161)