Trump Commuted His Sentence. Now the Justice Department Is Going To Prosecute Him Again.

Philip Esformes' case is a story about what happens when the government violates some of its most basic promises.

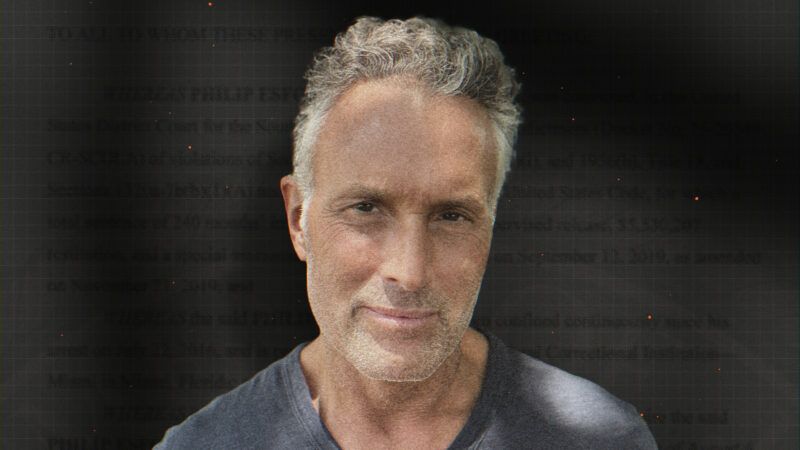

When Philip Esformes walked out of prison in December 2020, he'd spent four and a half years behind bars, the majority of which were in solitary confinement. He reportedly weighed about 130 pounds. He was, in many ways, a broken man. But Esformes' luck was changing: He had recently received clemency from former President Donald Trump, giving him the chance to rebuild his life after paying a debt to the country.

That fortune has quickly soured.

In a move that defies historical precedent, the Department of Justice under President Joe Biden is using a legal loophole to reprosecute Esformes' case—raising grave questions about double jeopardy, the absolute power of the clemency process, and the weaponization of the criminal legal system against politically expedient targets.

A former executive overseeing a network of skilled nursing and assisted living facilities, Esformes was arrested in 2016. The prosecutors, who were found to have committed substantial misconduct throughout the case, alleged he paid doctors under the table to send patients his way and subsequently charged Medicare and Medicaid for unnecessary treatments. The government held him without bond in the years leading up to his trial, placing him in solitary. He was ultimately found guilty of money laundering and related charges, as well as bribing regulators to give him notice of upcoming inspections so he could attempt to obscure shoddy conditions at those facilities.

But Esformes was not convicted of the most serious charges leveled against him. The government failed to convince a jury, for example, that he committed conspiracy to commit health care fraud and wire fraud. So his 20-year sentence—handed down by U.S. District Judge Robert N. Scola of the Southern District of Florida—may appear grossly disproportionate to his convictions.

Until you realize the judge explicitly punished Esformes for charges on which the jury hung.

That is not an error. "When somebody gets sentenced [at the federal level]…they get sentenced on all charges, even the ones they're acquitted on, [as long as] they get convicted on one count," says Brett Tolman, the former U.S. Attorney for the District of Utah who is now the executive director of Right on Crime. It is a little-known, jaw-dropping part of the legal system: Federal judges are, in effect, not obligated to abide by a jury's verdict at sentencing. They can, and do, sentence defendants for conduct on which they were not convicted. In this case, Esformes was already sentenced—and had that sentence commuted—for the crimes that the DOJ now wants to retry.

"This defendant, as much as you might not like him…do you think he should be punished two or three times for the same conduct?" asks Tolman. "I don't find anybody who thinks that's fair."

Esformes is just one person. And he's perhaps a convenient bullseye at which the Biden administration and Attorney General Merrick Garland can aim, as many on the left have a particular sort of ire for white-collar crime. But it is difficult to overstate the implications of his case for the broader public, regardless of partisan affiliation.

"While there are a lot of people who disagree with how Donald Trump handled his clemencies, it's his absolute right as a president to issue commutations and pardons. And I think that's an important right to protect," says the prominent left-leaning attorney and advocate Jessica Jackson, who was instrumental in shepherding the passage of the FIRST STEP Act. "Philip is struggling with anxiety and depression. He's been triggered by the threat of being reprosecuted and brought back to a prison where he was assaulted multiple times…. It might be Philip Esformes today, but it could be thousands of young mothers and fathers stuck in the system tomorrow."

A Case Tainted by Prosecutorial Misconduct

The government's misbehavior in the Esformes case was "deplorable," wrote U.S. Magistrate Judge Alicia Otazo-Reyes in August 2018.

In 2016, the FBI raided one of Esformes' medical facilities. The agency, as well as prosecutors, knew that the building contained documents subject to attorney-client privilege, which the government was therefore barred from seeing. That didn't stop them from retaining and reviewing such documents anyway—for months. They also leveraged government informants to secure recordings of private conversations between Esformes and his lawyers.

"This violates any person's right to defend themselves by virtue of the government having access to your communications and therefore your theory of your defense…. If [prosecutors] know in advance what the defense is going to be, and the particulars of that defense, that gives the government a hand up," says Michael P. Heiskell, owner of Johnson Vaughn & Heiskell and President-elect of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL). "This intrusion offends bedrock principles of our American criminal legal system and taints the legitimacy of the adversarial process and assurance of justice."

Otazo-Reyes spared few prisoners in her sprawling opinion, which exceeded 100 pages, though she stopped short of barring further prosecution. That was likely to be expected. What was not necessarily expected is that she allowed those same prosecutors to stay on the case after gaining privileged information they were legally barred from seeing.

In November 2018, Judge Scola—the same judge who would later sentence Esformes—agreed the prosecutors had been "sloppy, careless, [and] clumsy." The government "conducted multiple errors over the course of its investigation," he said. And he, too, would ultimately rule that those prosecutors could stay on the case as it went to trial, despite the fact that their misconduct was so comprehensive it necessitated they hire their own private counsel—a significant step when considering prosecutors are protected by absolute immunity and rarely have to worry about consequences for misbehavior on the job.

That development is "remarkable," adds Heiskell. "It is very troubling that prosecutors have been allowed—and still, in many instances, are allowed—willy-nilly to just flaunt their ethical obligations, and even the laws in many respects, to prosecute an individual."

Not Convicted, but Still Sentenced

After an eight-week trial, Esformes stood in federal court in September 2019 wearing an oversized khaki prison uniform. Though convicted on 20 counts, a jury failed to deliver a verdict on the most serious allegations in what prosecutors said was a $1.3 billion scheme to defraud Medicare and Medicaid. It is somewhat unclear how the government arrived at that massive number, and the charges for which Esformes was convicted came nowhere close to those damages. Apart from his 20-year prison term, he was also ordered to complete three years of supervised release, to pay $5.5 million in restitution, and to forfeit $38.7 million, none of which was absolved with Trump's commutation. The government has seized about $30 million so far via his bank accounts, vehicles, and properties.

But Esformes' stratospheric sentence wasn't necessarily a surprise in federal court, where defendants can be punished for charges a jury declines to convict them of.

Judge Scola made no secret of it. In a November 2019 restitution hearing, he acknowledged that Esformes' sentence was a product of the hung counts and thus questioned the government on the utility of continuing to pursue the case. "I don't know what more you are going to get out of the case if you try those additional counts," he said—because Esformes had already been sentenced for them.

In reply, Assistant U.S. Attorney Elizabeth Young agreed. "Certainly, Your Honor, if the case comes back on appeal, we would ask the hung counts to run with the appeal so the whole thing could be retried," she answered. "We have entered into agreements to dismiss the hung counts if the defendant's appeal is dismissed, and we would agree to do so here."

Put more plainly, the prosecution promised to drop the hung counts entirely if they were no longer part of the full indictment. Esformes had been punished as if the hung counts came back as convictions. But that scenario is now the reality: The hung counts are no longer part of the full indictment. The prosecution is proceeding anyway.

That defendants receive prison time for charges on which they weren't convicted—and sometimes for conduct that wasn't even charged—likely flies in the face of many people's basic understanding of the U.S. criminal justice system.

"I tend to put it…in terms of the elementary school or high school civics vision of how we think justice works, which is presumed innocent until proven guilty, and then only subject to criminal punishment for what you're proven guilty of," says Doug Berman, a professor of law at Ohio State University and author of the Sentencing Law and Policy blog. "To the extent that we look at other nations and hear about people incarcerated or subject to all sorts of other problematic treatment, I think we worry about that based in part on the assumption they haven't gotten the kind of due process that…is sort of at the core of our own vision of what makes our system great—or so we think."

In the topsy-turvy world of federal court, that presumption is turned on its head. So long as the defendant is convicted of something, a judge can consider the charges a jury acquitted him of, or on which they rendered no verdict at all, when determining how long he should spend in prison. It is a practice that has drawn broadsides from legal scholars of diverse persuasions, from U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh to former Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, as a potential violation of the Fifth Amendment right to due process and the Sixth Amendment right to a trial by jury.

The high court will soon announce if it will clarify its jurisprudence on the subject if they agree to hear a case concerning a man named Dayonta McClinton, who was sentenced to 19 years for a robbery when the maximum recommended punishment was less than six years. U.S. District Judge Tanya Walton Pratt openly acknowledged that the "driving force" behind that sentence was McClinton allegedly causing the death of one of his co-conspirators. He was found not guilty of that charge.

But any potential decision won't come soon enough for Esformes, who is facing an even stranger ordeal: someone whose sentence was commuted and will soon go back on trial—for charges on which he was already punished.

Tried, and Tried Again

Central to the most rudimentary understanding of the U.S. legal system is the protection defendants are promised against double jeopardy—the safeguard that prohibits prosecutors from trying and punishing you multiple times for the same crime.

Esformes' second prosecution "directly violates the double jeopardy clause," says Tolman. "The jury has been impaneled, so double jeopardy attaches, you're in the same jurisdiction, and the judge has indicated that he's sentencing him for [the hung counts]."

Jackson agrees. "If you walk through the facts, it's clearly double jeopardy," she says. "The judge on the record at sentencing used the hung conduct as part of his sentence…. That sentence was then commuted by President Trump. In my mind, while it's a novel area of legal precedent, this is double jeopardy by the letter of the law, really."

Esformes' case thus presents a question for the Department of Justice: How can it proceed with the prosecution against him when he was already sentenced, and had that sentence commuted, for the charges it wants to retry?

Some in the government are trying to answer that. "I [am inquiring] as to how the United States Department of Justice could believe that any further prosecution of Mr. Esformes on charges for which he was already tried, sentenced and granted clemency by the President of the United States could possibly be constitutionally permitted, and in all events a proper use of United States government resources?" asked Sen. Mike Lee (R–Utah) in a recent letter to Attorney General Garland.

The query has yet to receive a response. Perhaps Garland finds himself in a politically awkward position: Some of Trump's clemency recipients, including Esformes, were widely deemed unsympathetic. But setting a precedent in which changing administrations can countermand the previous president's clemency decisions is a dicey game, should you want to ensure the security of future recipients you find more palatable. Principles, by definition, are not actually principles if you discard them when the moment is opportune.

That Esformes received clemency does not detract from the fact that there are many defendants who are fit for a second chance. The two things are not mutually exclusive. "It's not about whether or not…somebody deserves it more," says Jackson. "I 100 percent agree that there are more people inside of our system who deserve commutations, and that's why myself and others have been pushing on the last three administrations to create a more robust clemency process—not one in which people have to worry about whether or not they're going to be sent back to prison after getting clemency."

But unless Garland opts to change course, Esformes finds himself in that very position: hurdling toward a retrial on charges for which he has been punished, challenging some of the basic legal protections we are promised in this country. "Another important player in our constitutional system, arguably the most important in terms of checking the misuse of government power, namely this historic, king-like power of clemency, has said: 'I don't think it's worth it to go after this guy,'" says Doug Berman. "That not only should be respected, but it should be the end of the story."

Show Comments (113)