The Best Inflation News This Week Actually Came Out of Congress

Inflation fell to 6.5 percent in December, but new House rules ensure that Congress will have to consider the inflationary impact of future spending bills.

Inflation slowed again during December, offering further hope that the worst of last year's price increases is now in the past.

And maybe there's reason to hope that lawmakers have learned a lesson about how government policy worsened that crisis, too.

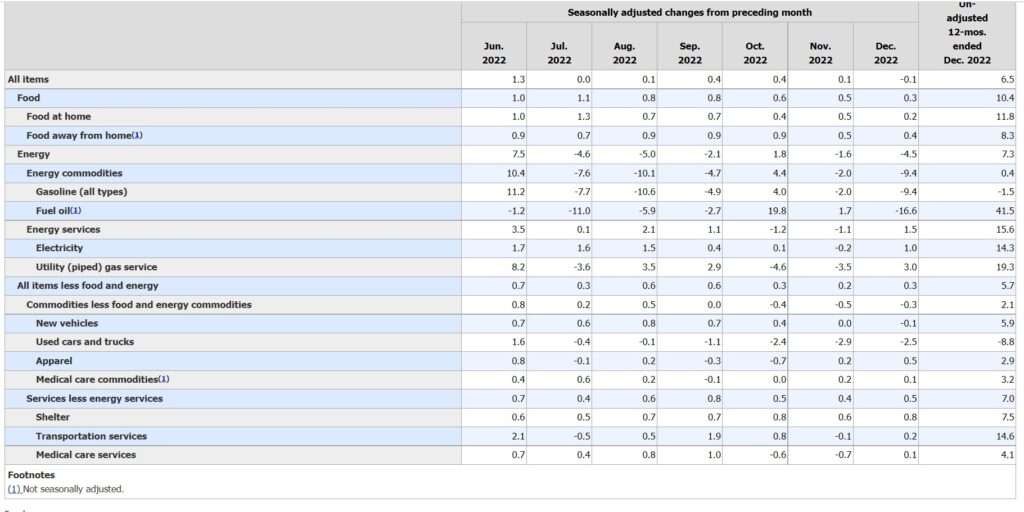

Bureau of Labor Statistics data released Thursday morning show that prices were 6.5 percent higher in December than they had been 12 months earlier. That's down from the 7.1 percent annualized inflation rate posted in November and far better than the peak rate of 9.1 percent in June. The falling number is undoubtedly welcome after the past year, even though 6.5 percent inflation far exceeds the Federal Reserve's goal and would have been seen as absurdly high less than two years ago.

One further encouraging sign: So-called core inflation, which filters out more volatile categories like food and fuel prices, rang in at a reasonable 3.1 percent over the final three months of 2022. Overall inflation was just 1.8 percent during that same period. That means additional declines in the top-line rate should be coming throughout the first half of 2023, as the early months of 2022 drop out of the annualized rate calculation.

Even so, the details of December's consumer price index report are a bit of a mixed bag. The overall decline in prices was driven by lower prices for gasoline, airfare, and used cars.

But housing and food prices continued to batter Americans' wallets in the final month of the year. Housing prices were up 0.8 percent in December and have increased by 7.5 percent over the past year. Grocery prices have climbed by 11.8 percent in the past 12 months. That's staggeringly high, but actually represents the lowest annualized rate for food prices since April.

Last year's runaway inflation had several causes: the massive surge in pandemic spending that bulged household budgets, the Federal Reserve's monetization of piles of pandemic-era debt, supply chain problems, and the war in Ukraine, among other things. But lawmakers and the Biden administration added fuel to the fire with the passage in March 2021 of the American Rescue Plan, a bill that several prominent economists warned would cause inflation to spike. Subsequent studies have shown that those warnings were accurate.

Even though inflation is now easing, the impact of federal spending on consumer prices will continue to be part of the discussion when Congress considers new spending bills. As part of the new rules package approved by House Republicans this week, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) will now be required to score legislation on projected macroeconomic effects—including inflation.

That's a welcome change that will provide more information to lawmakers and the general public about the impact of spending bills. Recall that when Sen. Joe Manchin (D–W.Va.) objected to President Joe Biden's Build Back Better proposal because of how it might have worsened inflation, he and others had to rely on independent assessments from groups like the Penn Wharton Budget Model, a research initiative of the University of Pennsylvania. Those models will still be useful going forward, but they don't carry as much heft as official analyses from the CBO or JCT, which lawmakers have learned to treat as the official scorekeepers of federal fiscal policy.

If the past year and a half have taught us anything, it's that inflation is no longer a threat relegated to the distant past. Sharp price increases make everyone poorer, and spending bills can't be properly understood without accounting for their inflationary trade-offs.

Show Comments (30)