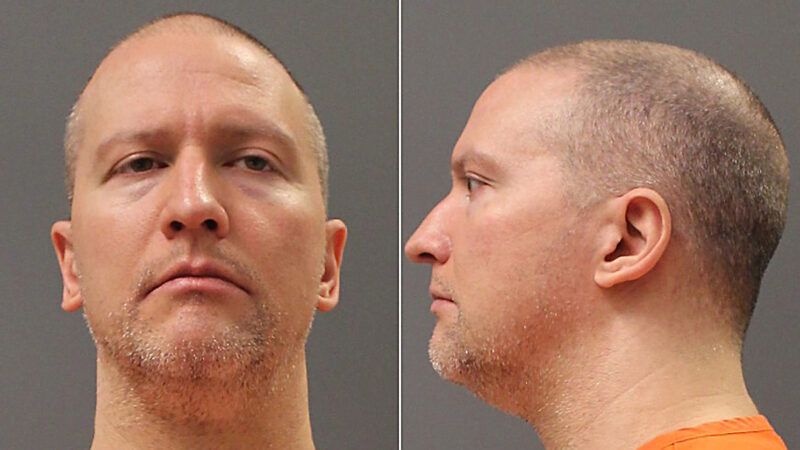

Even at His Sentencing Hearing, Derek Chauvin Did Not Manage To Express Remorse for Killing George Floyd

Despite the stakes, the former Minneapolis police officer could not bring himself even to feign regret for his actions.

Derek Chauvin, who received a 21-year federal sentence yesterday for lethally violating George Floyd's constitutional rights, still seems to think he did nothing wrong by kneeling on his victim's neck until he was dead. Judging from Chauvin's conspicuous failure to express remorse prior to his sentencing, he is sticking with the story he told at his state trial last year.

Prior to that trial, Chauvin's lawyer, Eric Nelson, blamed Floyd's death on an inept arrest by two rookie police officers, J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane, who were responding to a complaint that Floyd had used a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes from a convenience store. "If Kueng and Lane had chosen to de-escalate instead of struggle," Nelson said, "Mr. Floyd may have survived." That was an audacious defense in light of Chauvin's subsequent treatment of Floyd, which was cruelly indifferent at best and hardly a model of de-escalation.

During Chauvin's trial, which ended in guilty verdicts on all counts, Nelson argued that the ex-cop's actions were justified in the circumstances. He even presented an expert witness who preposterously maintained that the prolonged prone restraint, during which Chauvin pressed a handcuffed, terrified man to the pavement for nine and a half minutes, did not qualify as a use of force.

Chauvin did not speak at his state trial. But after his convictions, he offered his "condolences to the Floyd family," saying "there's going to be some other information in the future that would be of interest," and "I hope things will give you…some peace of mind." He added that he could not say more because of "additional legal matters at hand," presumably referring to the federal case. Yet even after those "legal matters" were resolved by a plea agreement in which Chauvin admitted to using excessive force against Floyd, Chauvin offered Floyd's family nothing beyond some good wishes.

The plea agreement called for a sentence of 20 to 25 years. In arguing for the lowest possible sentence, The Washington Post notes, Nelson cited his client's "acceptance of his wrongdoing." The Post reports that Nelson "spoke of Chauvin's 'remorse for the harm that has flowed from his actions' and told the court the former officer would demonstrate that at his sentencing." But that did not happen.

"In a brief statement during Thursday's hearing," the Post says, "Chauvin did not offer any formal apologies or remorse for his actions." Instead he wished Floyd's children well. "I just want to say I wish them all the best in their life," Chauvin said. He added that he hoped they would have "excellent guidance in becoming great adults."

Chauvin displayed the same condescending, unrepentant attitude toward John Pope, another victim of his brutality. As part of his agreement with the Justice Department, Chauvin pleaded guilty to using excessive force against Pope, then 14, in 2017. The encounter began with a complaint from Pope's mother, who said he had assaulted her. Although Pope "made no aggressive moves" against the officers who responded to that call, Chauvin admitted, he repeatedly hit Pope on the head with a flashlight and knelt on him for more than 15 minutes.

"I was treated as though I was not a human being by Derek Chauvin," Pope, now 19, said at the sentencing hearing. "He made a choice and did not care for the outcome." Pope, who until the encounter with Chauvin was getting good grades in school and planned to attend college, said the experience had upended his life, leaving him with a feeling of powerlessness that derailed his plans.

In his statement to the court, the Post notes, Chauvin "did not apologize to Pope but said he wished the man well." This is what Pope got in lieu of an apology: "I hope you have the ability to get the best education possible to lead a very productive and rewarding life." Chauvin also wished him "a good relationship with your mother."

Chauvin's lack of contrition for his crimes against Floyd and Pope is especially striking in this context, where he had already pleaded guilty and was looking for mercy from U.S. District Judge Paul Magnuson. Despite the stakes, Chauvin could not bring himself even to feign regret for his actions. "I really don't know why you did what you did," Magnuson said, "but to put your knee on another person's neck until they expired is simply wrong, and for that conduct you must be substantially punished."

Chauvin's mother, Carolyn Pawlenty, did not help his case. As The New York Times notes, she thought it was important to note that Chauvin had received thousands of supportive cards, "enough to fill a room of her house." Pawlenty cited her son's 20 years of service in the Minneapolis Police Department and complained that he had been abandoned by his colleagues, several of whom, including the police chief, testified against him in his state trial. In her view, they had "failed to back their own." The real victim, she implied, was Chauvin, not the man whose desperate pleas for relief he ignored while blithely pinning him to the street.

What Pawlenty perceives as a failure was actually a belated acknowledgement that the police department had for two decades continued to employ an officer who was manifestly unsuited for the job. According to the federal civil rights lawsuit that Floyd's family filed after his death, which led to a $27 million settlement with the city, Chauvin "engaged in a reckless police chase resulting in the deaths of three individuals" 15 years before he killed Floyd "but was not discharged." Between 2006 and 2015, the lawsuit noted, "Chauvin was the subject of 17 citizen complaints." Just one "resulted in discipline, in the form of a letter of reprimand."

When supervisors treat such complaints as evidence that an officer is simply doing his job rather than evidence that he has little regard for people's rights, they invite further abuses. That's the predictable result of the reflexive support that Pawlenty thinks Chauvin's colleagues should have offered after he killed Floyd. The same impulse explains the thousands of cards that Pawlenty cited as evidence of her son's good character.

A habit of uncritical deference also explains the inaction of the three officers—Lane, Kueng, and Tou Thao—who failed to stop Chauvin, the senior officer at the scene, from crushing the life out of Floyd. In February, a federal jury convicted Lane, Kueng, and Thao of violating Floyd's rights by failing to intervene or render medical aid. They were also charged with state crimes. Lane, the only officer who dared to suggest that continuing to pin Floyd facedown on the pavement might be inadvisable, pleaded guilty to a state manslaughter charge in May and is scheduled to be sentenced in September. The state trial of Kueng and Thao is scheduled to begin in January.

Such serial prosecutions have been blessed by the Supreme Court, which deems them consistent with the Fifth Amendment's ban on double jeopardy even when the elements of the state and federal offenses are the same. In these cases, the elements are different, since the federal crimes hinge on a willful deprivation of rights under color of law. Still, one might reasonably ask why it is necessary or appropriate to prosecute these four officers twice for the same conduct.

Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in the Twin Cities, suggests that Chauvin's second prosecution was necessary to send a message. "It was the federal government making a statement about this case being important nationally," Osler told the Times. "And it also was a conviction on something beyond what we saw in the state. It was about the deprivation of civil rights, not just the killing of George Floyd."

While Chauvin had never been prosecuted for his attack on Pope, he had already received a sentence of more than 22 years under state law for killing Floyd. But since Chauvin will be serving the two sentences concurrently, the main practical impact of the federal case will be that he serves his time in federal prison, which is preferable from his perspective because it means he is less likely to encounter people he arrested in Minneapolis. Chauvin has been in solitary confinement at a state prison in St. Paul since he was convicted in April 2021.

It seems doubtful that the federal prosecution was necessary to show that Floyd's death, which provoked bipartisan disgust, protests across the country, and police reforms in various cities and states, was "important nationally." And what was the state jury that convicted Chauvin of murder doing if not vindicating Floyd's rights as an American citizen and a human being? But if nothing else, the federal case gave Chauvin another opportunity to acknowledge the grievous wrong he had done. Apparently, that was still more than he could manage.