The Convictions of 3 Cops Who Failed To Prevent George Floyd's Death Underline the Duty To Intervene

The defendants unsuccessfully argued that their training was inadequate and that they understandably deferred to a senior officer.

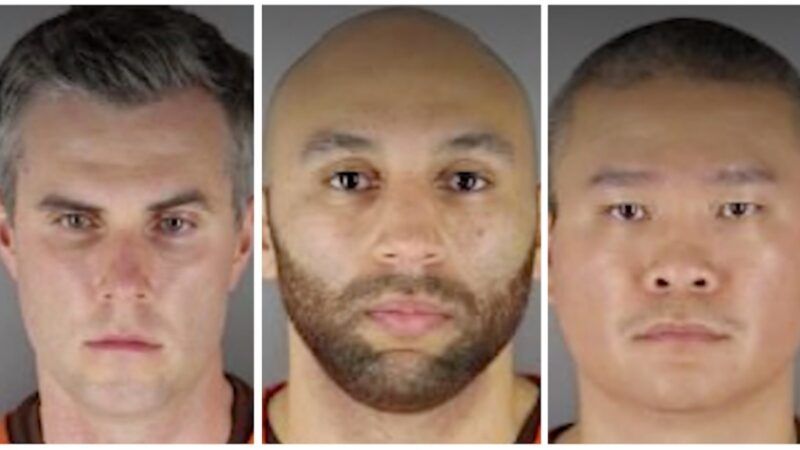

Three former Minneapolis police officers were convicted in federal court yesterday of failing to intervene or render medical aid as their colleague, Derek Chauvin, killed George Floyd by pinning him face-down to the pavement for nine and a half minutes on May 25, 2020. After deliberating for about 13 hours, the jury concluded that Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng, and Tou Thao had violated 18 USC 242 by depriving Floyd of his constitutional rights under color of law. Because the jury also concluded that Floyd's prolonged prone restraint caused his death, the three defendants could face lengthy prison sentences.

Chauvin, who was convicted of murdering Floyd last April, is serving a state sentence of 22.5 years. He pleaded guilty in December to violating the same federal law under which Lane, Kueng, and Thao were charged. The focus of the case against them was not what they did that day but what they failed to do. Their convictions send a powerful message about the legal peril for police officers who ignore their duty to stop colleagues from using excessive force.

The encounter that led to Floyd's death began when Lane and Kueng, both of whom were in their first week as full-fledged police officers, arrested him for using a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes at Cup Foods, a restaurant and convenience store on Chicago Avenue. Chauvin, a 19-year veteran who had been Kueng's training officer, arrived as the two rookies were unsuccessfully trying to force a distraught Floyd into the back seat of their squad car.

After Chauvin took charge, Floyd was handcuffed and forced to lie on his stomach as Chauvin knelt on his neck, Kueng applied pressure to his back, and Lane held his legs. He remained in that position until he died, after complaining, over and over again, that he could not breathe. Thao, meanwhile, was charged with keeping a group of concerned bystanders away from Floyd and the other three officers. A bystander video of the incident provoked bipartisan outrage, nationwide protests, and the four officers' dismissal.

Since the charges against Lane, Kueng, and Thao alleged that they "willfully" deprived Floyd of his rights, one of the issues in the trial was whether they knew that Chauvin was using excessive, potentially lethal force. That should have been obvious, the prosecution argued, given Floyd's pleas for relief and the repeated warnings from witnesses who recognized that his life was in danger. By the time Floyd lost consciousness, in any event, it should have been clear that he needed medical attention and that his continued restraint was utterly gratuitous. Even after Floyd no longer had a detectable pulse, Chauvin kept his knee on his neck.

"For more than nine minutes, each of the three defendants made a conscious choice over and over again not to act," federal prosecutor Samantha Trepel told the jury. "They chose not to intervene and stop Chauvin as he killed a man slowly in front of their eyes on a public street in broad daylight."

Lane clearly recognized the danger, since he repeatedly suggested that Floyd should be rolled onto his side, which was consistent with what officers are taught about the risk of "positional asphyxia" during prolonged prone restraints. Unlike the other two defendants, Lane was not charged with failing to stop Chauvin from using excessive force. But like them, he was charged with failing to perform CPR or move Floyd into a position in which it would have been easier to breathe.

The defendants argued that their training had been inadequate to prepare them for this situation. They also argued that they understandably deferred to Chauvin, the senior officer at the scene.

Thao, unlike Lane and Kueng, was not a rookie; he had been employed by the Minneapolis Police Department for about 11 years. But his lawyer argued that Thao was not close enough to clearly understand what was happening and that he was distracted by his crowd and traffic control duties.

The jury clearly did not buy that excuse. The bystanders were angry precisely because they correctly believed that Chauvin was killing Floyd, and Thao reacted to their complaints by falsely assuring them that Floyd was fine. He even seemed to make light of the situation, saying, "This is why you don't do drugs, kids."

Instead of dismissing the bystanders' warnings, the prosecution argued, the defendants should have recognized that the witnesses were right. "After Mr. Floyd lost the ability to speak, the people on the sidewalk stood up for him," Trepel said. "They understood just by seeing his body go limp, listening to his words and then listening to his silence that, unless somebody changed what was happening, he would die."

Lane, Kueng, and Thao still face state charges that they aided and abetted Chauvin's crimes. Their state trial, which is scheduled to begin on June 13 in Hennepin County District Court, will focus on whether they "intentionally aided" Chauvin in committing felony murder and second-degree manslaughter.

After the state charges were filed, Ted Sampsell-Jones, a professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, noted that they are "legally valid under Minnesota law" but "rely on some fringe doctrines of accomplice liability." Those doctrines, he added, "have long been criticized by progressive reformers" because they "create expansive strict liability for minor participants in group crimes."

Show Comments (53)