The Year's Best Drug Scares

Impossibly potent marijuana edibles, formaldehyde in e-cigarettes, pills of war, MDMA disguised as Halloween candy, and superhuman flakka zombies.

Believability is key to a good drug scare, because if it doesn't catch on it's not much of a scare. At the same time, you have to admire claims that catch on even though a moment's reflection reveals them as ridiculous. The trick for an aspiring drug scare is to forestall reflection by being so compelling and repeatable that it gets passed around before anyone has time to think. In this annual list I recognize tall tales about drugs that rise to the challenge.

5. Invasion of the Super-Potent Pot

In their 2015 book Going to Pot, former drug czar Bill Bennett and New Jersey lawyer Robert White argue that rising THC concentrations effectively make cannabis, a substance that humans have been consuming for thousands of years, a new drug with unknown hazards. "You cannot consider it the same substance when you look at the dramatic increase in potency," they write. "It is like comparing a twelve-ounce glass of beer with a twelve-ounce glass of 80 proof vodka; both contain alcohol, but they have vastly different effects on the body when consumed."

Bennett and White completely ignore the possibility that people take potency into account when deciding how much is enough. Just as drinkers do not treat 12 ounces of vodka as equivalent to 12 ounces of beer, cannabis consumers adjust their intake based on the strength of the strain. Anyone who is accustomed to smoking a whole bowl of mediocre black-market weed will quickly learn he should not treat a Denver marijuana merchant's Chemdawg 4 or Girl Scout Cookies the same way.

While no one would accuse Bennett and White of bringing nuance to this subject, Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska, Sheriff Mark Overman outdid their pot potency panic in a March op-ed piece that sought to explain why he joined a lawsuit seeking to reverse marijuana legalization in neighboring Colorado. "Almost all of the marijuana that we see originates in Colorado," he writes. "The potency has increased dramatically."

Overman says "the smoking variety" of Colorado marijuana "commonly tests over 20 percent." That's rather misleading, since such super-strong strains remain the exception rather than the rule. The Green Solution, a chain of cannabis retailers in Colorado, lists 57 varieties of buds on its website, 36 of which (almost two-thirds) have THC concentrations below 20 percent, many far below.

Overman moves from exaggeration to fabrication when he claims that "'edibles,' in the form of candy, baked goods, and drinks, have [THC] levels as high as 90 percent." That can't possibly be true, since a lollipop or soda that was 90 percent THC would not be a lollipop or soda; it would be THC sprinkled with sugar. Furthermore, Colorado's regulations limit edibles to no more than 100 milligrams of THC per package. A legal edible that was 90 percent THC therefore would weigh no more than 111 milligrams, or 0.004 ounce. That's a pretty tiny candy bar.

4. Fear of Formaldehyde

A letter published by the New England Journal of Medicine last January reported a study in which researchers analyzed the aerosol produced by an e-cigarette tank system (a refillable vaporizer with a variable-voltage battery) and "did not detect the formation of any formaldehyde-releasing agents." Naturally, this finding seized the attention of news outlets around the country, leading to headlines such as "No Formaldehyde in Ecig Vapor" and "Study Confirms That Vaping Is Safer Than Smoking."

Just kidding. For some reason, reporters latched onto another result from the same study, suggesting that a vaper could inhale more than four times as much formaldehyde as a pack-a-day smoker. That finding led to headlines such as "E-Cigarettes Can Produce More Formaldehyde Than Regular Cigarettes, Study Says" and "E-Cigarette Vapor Filled With Cancer-Causing Chemicals, Researchers Say."

According to the researchers, the difference between those dramatically different results was the voltage setting. At low voltage, the tank system produced no formaldehyde; at high voltage, it produced lots of formaldehyde. But as critics such as Boston University public health professor Michael Siegel were quick to point out, the conditions in the latter test were unrealistic, leading to overheating that would make a human vaper, as opposed to a machine, stop puffing. Siegel noted that such overheating creates "a horrible taste which a vaper could not tolerate," known as the "dry puff phenomenon." He concluded that "extrapolating from this study to a lifetime of vaping is meaningless."

The researchers extrapolated anyway, estimating that vapers might face a formaldehyde-related cancer risk "5 times as high…or even 15 times as high…as the risk associated with long-term smoking." Later one of the researchers conceded that such speculation was a bit premature. "It's way too early now from an epidemiological point of view to say how bad [e-cigarettes] are," James Pankow, a professor of chemistry and engineering at Portland State University in Oregon, told NBC News. "But the bottom line is, there are toxins, and some are more than in regular cigarettes. And if you are vaping, you probably shouldn't be using it at a high voltage setting."

The implication—that vapers in the real world are apt to generate levels of formaldehyde similar to those generated by Pankow et al.'s machine—is highly misleading. Worse, this sort of misinformation is potentially lethal, to the extent that it discourages smokers from switching to vaping, which is indisputably much less dangerous.

Pankow told NBC "we are not saying e-cigarettes are more hazardous than cigarettes." But that is the impression left by the NEJM letter and the news stories it inspired. He noted that "we are only looking at one chemical" out of the thousands that can be found in tobacco smoke, of which hundreds are toxic or carcinogenic. "The jury is really out on how safe these drugs are," he said. According to Reuters, "Pankow conceded that the study could have contained more context about overall relative risk, but said the authors 'just wanted to get it out.'"

3. Courage in a Pill

Soldiers have been using amphetamines to stay awake and alert since World War II. Captagon, a combination of dextroamphetamine, the main ingredient in Adderall, and theophylline, a stimulant in the same class as caffeine, was prescribed for decades as a treatment for obesity, depression, and hyperactivity. Yet this year sensational news stories managed to make the old and familiar new and scary by linking Captagon to Syria's civil war.

The Washington Post described Captagon as "a tiny, highly addictive pill" that is "fueling Syria's war and turning fighters into superhuman soldiers." The Post's Peter Holley claimed "Captagon quickly produces a euphoric intensity in users, allowing Syria's fighters to stay up for days, killing with a numb, reckless abandon." Drawing on anecdotes from a 2015 BBC documentary and a 2014 Reuters story, Holley left the impression that Captagon enables members of various armed groups in Syria to fight without fear, kill without hesitation or remorse, and resist brutal interrogation, literally laughing at the pain. The next day Washington Times reporter Kellan Howell parroted Holley's claims, using the same secondhand quotes and strikingly similar language.

Such breathless accounts do not reflect Captagon's properties so much as reporters' perennial willingness to believe outlandish claims about drugs other people take. Captagon is an "inferior amphetamine" whose effects are "nowhere near what the media reports have been talking about," Columbia University neuropsychopharmacologist Carl Hart told Live Science. "Trust me, if this drug produced a supersoldier, U.S. soldiers would be using it."

2. Good Golly, It's Molly!

In 2014 the top position in my list of the year's best drug scares was occupied by the mythical menace of cannabis candy in trick-or-treat bags. This year we saw a creative variation on that theme: candy-colored MDMA tablets in trick-or-treat bags.

Snopes.com, the online catalog of urban legends, traces the scare to a September 25 post by a Facebook user named Thomas Chizzo Bagwell featuring a photo of colorful Molly tablets. "If your kids get these for halloween," Bagwell wrote, "it's not candy." A few weeks later, the Jackson, Mississippi, police department posted the same photo, accompanied by this warning:

If your kids get these for Halloween candy, they ARE NOT CANDY!!! They are the new shapes of "Ecstasy" and can kill kids through overdoses!!! So, check your kid's candy and "When in doubt, Throw it out!!!" Be safe and always keep the shiny side up!!!

That burst of fact-free fear, which was later removed from the police department's Facebook page, transformed idle speculation into "an alert" issued by "police nationwide," as WILX, the NBC station in Lansing, Michigan, put it. WOIO, the CBS station in Cleveland, claimed "Ecstasy masked to look like candy" is "popping up all over the country, and police want to warn you." If a child were to eat one of those tablets, according to Westlake, Ohio, Police Capt. Guy Turner, "they would be in the emergency room without a doubt."

Why did Turner think that scenario was plausible? "Look at the colors," he told WOIO. "They're very similar to, like, Sweet Tarts or Sprees or Smarties. These people, they just piggyback off legitimate stuff." As Snopes.com writer Kim LaCapria noted, candy-colored MDMA tablets have been around for years. The same photo that Bagwell, Jackson police, and their collaborators in the press used to frighten parents of trick-or-treaters had previously accompanied general stories about recreational MDMA use.

One widely carried TV report, credited to NBC, said "just one of those candy pills would cost about $10," which suggests "it's rare that it would pop up in your child's trick-or-treat bag." Still, "police do want you to be aware." In other words, there is no evidence that anyone has ever contemplated giving trick-or-treaters MDMA tablets, let alone actually done it, but you should worry about it anyway.

1. The Devil's Drug

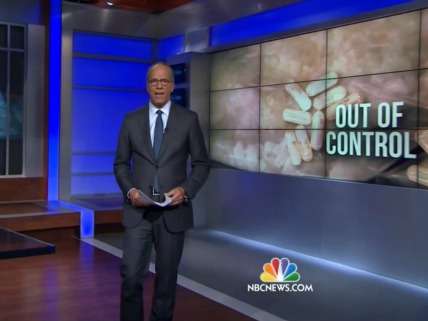

By now scary stories about the synthetic cathinones sold as "bath salts"—sometimes involving people who have not even taken them—are old hat. But this year yellow journalists showed they could get more mileage from the same claims by focusing on one of those cathinones, alpha-PVP, rebranded as flakka. According to a typically over-the-top account posted by NBC News last week, flakka is a "devil's drug" that is "driving Florida insane." Reporters Cynthia McFadden, Aliza Nadi, and Tracy Connor matter-of-factly describe flakka, which they also call "five-dollar insanity," as a "cheap, crazily addictive and terrifying" stimulant that is "wreaking havoc in South Florida." They attribute magical powers to flakka, saying it transforms people into "paranoid zombie[s] with superhuman strength and off-the-charts vital signs."

Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel columnist Daniel Vasquez agrees that flakka "turns people into zombies." Vasquez says flakka "leads users to attack people or commit suicide," so "if you come across someone high on flakka," you should "run for your life." Apparently these are the fast kind of zombies. The Washington Post's Peter Holley, who can always be counted on to regurgitate anti-drug hysteria, confirms that these zombies are not to be trifled with, calling flakka "the new drug that causes users to rip off their clothes and attack with super-human strength."

Tales of superhuman strength have been associated with various drugs over the years, including cocaine in the early 1900s, marijuana in the 1920s and '30s, and PCP (a.k.a. angel dust) in the 1970s and '80s. "The notion that drugs produce superhuman strength is simply not true," says Hart, the Columbia drug expert, who studies the effects of stimulants such as crack cocaine and methamphetamine. "It has never been shown. This is just a continuation of the theme. It should raise red flags for people if they see 'superhuman strength.'"

Like the local reports and earlier national stories from which it draws, the NBC account relies on sources whose work brings them into contact with extreme, nonrepresentative samples of drug users: "An emergency room doctor calls it as 'five-dollar insanity.' A rehab director says it's the 'devil's drug.'… 'I talk to patrol and they say it's every other call some nights…just one after the other, all flakka-related calls,' said Capt. Dana Swisher of the Fort Lauderdale Police Department."

These stories recycle the same handful of anecdotes about flakka users who hurt themselves, attacked others, or ran through the streets naked. They present these cases, which were unusual enough to generate TV reports and newspaper headlines, as typical of flakka users, in some cases transforming a single incident into multiple events. In NBC's report, for instance, a guy who got stuck while climbing the fence around the Fort Lauderdale police station last March becomes "users…impaling themselves on fences."

The news outlets hyping this "epidemic" want you to believe that many, if not most, flakka users behave this way. They also want you to believe the drug is wildly popular. Both of those things cannot be true, since people generally do not like using drugs that send them to jail or the hospital. As Hart observes, "The fact that the vast majority of the people who use these substances don't exhibit that behavior tells you that it's not the drug."

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Show Comments (9)