A Law Professor's Beef With a First Amendment 'Spinning Out of Control': Too Much Speech of the Wrong Sort

Even as he praises judicial decisions that made room for "dissenters" and protected "robust political debate," Tim Wu pushes sweeping rationales for censorship.

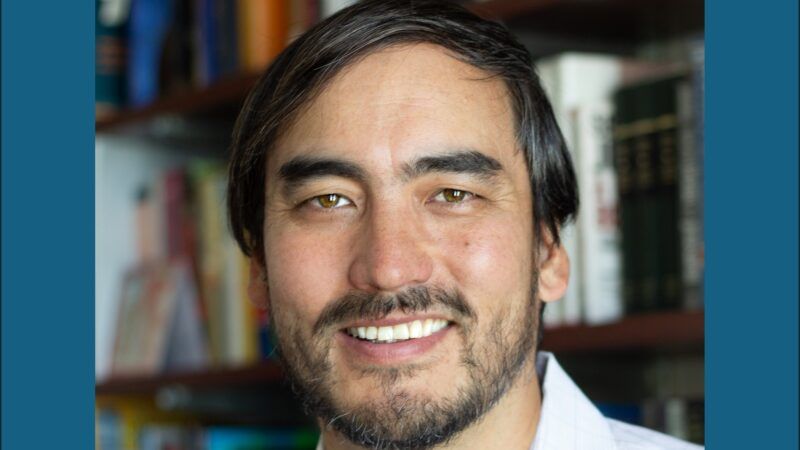

"The First Amendment is spinning out of control," Columbia law professor Tim Wu warns in a New York Times essay. While Wu ostensibly objects to Supreme Court decisions that he thinks have interpreted freedom of speech too broadly, his complaint amounts to a rejection of the premise that the principle should be applied consistently, especially when it benefits speakers and messages he does not like.

The immediate provocation for Wu's diatribe is yesterday's Supreme Court decisions in two cases challenging Florida and Texas laws that aimed to restrict content moderation on social media. Although the justices remanded both cases for further consideration by the lower courts, Justice Elena Kagan's majority opinion in Moody v. NetChoice made it clear that the "editorial discretion" protected by the First Amendment extends to the choices that social media platforms make in deciding which content to host and how to present it, even when those decisions are inconsistent, biased, or arguably unfair. And that discretion, she said, includes the use of algorithms that reflect such value judgments.

Although Wu has reservations about "the wisdom and questionable constitutionality of the Florida and Texas laws," he thinks "the breadth of the court's reasoning should serve as a wake-up call." He faults the justices for "blithely assuming" that "algorithmic decisions are equivalent to the expressive decisions made by human editors at newspapers." The ruling, Wu says, reflects a broader trend in which "liberal as well as conservative judges and justices have extended the First Amendment to protect nearly anything that can be called 'speech,' regardless of its value or whether the speaker is a human or a corporation."

As Wu sees it, freedom of speech should hinge on the "value" of the ideas that people express. It is hard to imagine a broader license for government censorship.

Wu praises decisions that protected the speech rights of "political dissenters, religious outcasts, intrepid journalists and others whose ability to express their views was threatened by a powerful and sometimes overbearing state." In those cases, he says, "the First Amendment was a tool that helped the underdog" and ensured "robust political debate." It is not hard to imagine how "the underdog" or "robust political debate" would fare under a legal regime that empowered the government to decide which speech is valuable enough to merit toleration.

Wu faults the Supreme Court for holding, in the 2012 case United States v. Alvarez, that the First Amendment protects "even outright lies," as he puts it. Again, allowing the state to suppress speech that it deems inaccurate would pose a chilling threat to "dissenters" of all stripes.

The First Amendment, Wu worries, "is beginning to threaten many of the essential jobs of the state, such as protecting national security and the safety and privacy of its citizens." Like "value" and accuracy, "national security" and "safety" are vague, subjective excuses for speech restrictions that sweep much more broadly than Wu might like.

Under the rationale of "national security," Wu thinks the government should aggressively resist "informational warfare," which he says entails banning TikTok, despite the impact that would have on the 122 million Americans who use the platform for purposes that even he would concede have something to do with rights guaranteed by the First Amendment. The struggle against "informational warfare" presumably also would include censoring the online speech of people identified (perhaps incorrectly) as foreign agents. Wu might hope that speech restrictions justified in the name of national security would stop there, but history suggests otherwise.

Wu also thinks the First Amendment should not apply to individuals who organize themselves as corporations. He predictably criticizes Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the 2010 decision in which the Supreme Court rejected legal restrictions on political speech by labor unions and corporations, including small businesses and myriad nonprofits representing a wide variety of views. "If the First Amendment has any force," Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the majority, "it prohibits Congress from fining or jailing citizens, or associations of citizens, for simply engaging in political speech." Kennedy rightly wondered why individuals should lose the right to freedom of speech merely because they seek to exercise it as "an association that has taken on the corporate form."

Glossing over the diversity of organizations affected by such a rule, Wu says "judges have transmuted a constitutional provision meant to protect unpopular opinion into an all-purpose tool of legislative nullification that now mostly protects corporate interests." That is especially worrisome, he avers, because "the power of private actors has grown to rival that of nation-states." Given his publishing history, you will not be surprised to learn that Wu thinks the "most powerful" of those private actors are "the Big Tech platforms, which in their cocoon-like encompassing of humanity have grown to control commerce and speech in ways that would make totalitarian states jealous."

Wu somehow overlooks a crucial distinction between Facebook et al. and "totalitarian states": While the former cannot use force to "control commerce and speech," blatant coercion is a defining feature of the latter. That difference has constitutional significance, although Wu apparently thinks it should not. To fight the supposedly state-like power of "Big Tech platforms," he wants to deploy actual state power, imitating the totalitarian techniques that he says pale in comparison to voluntary, consensual interactions with YouTube or Amazon.

The freedom of Big Tech (and Little Tech) to adopt a diversity of content-moderation policies, based on what they think users want, gives people options they would not have if the government overrode those decisions. And although Wu resists the idea, those choices are embodied by algorithms (created by humans!) that aim to organize an enormous amount of content in a way that is accessible, interesting, and useful. All of this supports the ability of individuals to go online, find information and opinions that interest them, and express themselves in one forum or another.

In case there was any doubt that Wu's beef is with the First Amendment itself, as opposed to any particular application of it, he closes by quoting Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson: "If the Court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact." Jackson made that comment while dissenting from the Court's 1949 decision in Terminiello v. Chicago, which overturned the "breach of peace" conviction of a priest who delivered an inflammatory speech.

Like Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes' 1919 analogy to "falsely shouting fire in a theatre," which he drew in support of the proposition that there was nothing wrong with imprisoning people for distributing anti-draft leaflets, Jackson's "suicide pact" warning is a go-to reference for anyone who wants to justify restrictions on constitutionally protected speech. Although those remarks have not aged well, Wu is trying hard to rehabilitate the attitude underlying them.

Show Comments (67)