American Journalism's Most Successful Politician To Step Down From Running The New York Times

Dean Baquet played a leading role in two of modern journalism's turns for the worse.

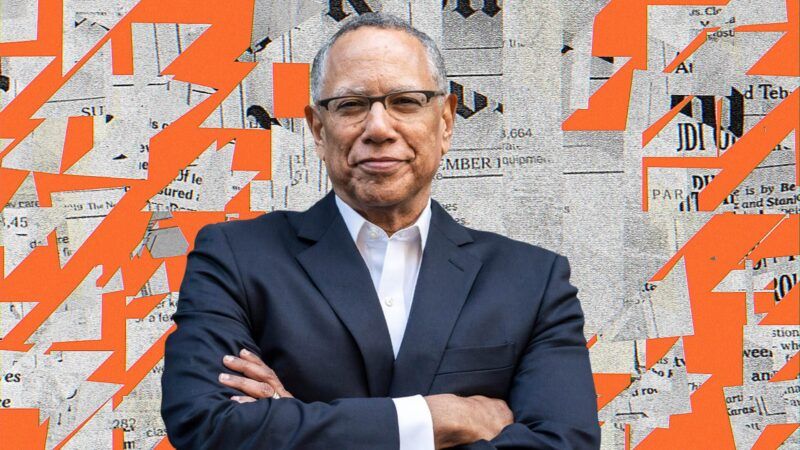

Outgoing New York Times Executive Editor Dean Baquet, whose long-groomed successor, Managing Editor Joseph F. Kahn, was announced to the world on Tuesday, has been elite journalism's most emblematic editor of the 21st century.

I do not intend that as a compliment.

The New York Times has far less kingmaking power, in both politics and culture, than it used to, but the Paper of Record still sets the tone for the newspaper industry and prestige journalism, and it is still capable of unmatched reportage, such as its valuable work from Ukraine. Decisions made (or not made) there end up getting replicated all over the media ecosystem.

There is much about Dean Baquet's career to admire, not least his inheriting a shrinking news business on Eighth Ave. in 2014 and then walking out eight years later with an enviable boom in digital subscriptions, business acquisitions, and newsroom hires.

"We were doing buyouts and layoffs," Baquet recalled at the end of a valedictory New Yorker interview in February. "So I do take credit for helping to transform the New York Times into a place that could survive and thrive, the way it is now….I do think that I helped make the New York Times a great investigative paper. I would argue the best investigative paper, whether it's the air-strike stories or it's getting Trump's taxes….We are more visual. What did I not get done? Frankly, if I look at the list of things I wanted to accomplish back then, I think we did pretty well. I can't think of anything big we didn't pull off."

Baquet has never lacked for self-regard, particularly when loftily defending "the best paper in the country" (as he also referred to the L.A. Times, erroneously, back when he edited that paper 16 years ago) from arrows slung from lower perches on the journalistic totem pole. That institutional haughtiness—most irritating to faster-moving competitors the Grey Lady might vaguely reference in follow-up coverage but almost never hyperlink—has extended to reporters challenging the paper's marquee work.

When Reason's Jim Epstein re-reported and cut to ribbons a 2015 Times Pulitzer-bait series ("The Price of Nice Nails") about alleged worker abuses at the immigrant-run nail salons so many of the paper's professional-class female readers like to frequent, it was Baquet's hand-waving dismissal of Reason as an illegitimate source of reporting that kept any people at the paper from publicly acknowledging their mistakes for more than a week.

"Until now, The Times has not responded to that series because editors believe they defended the nail salon investigation fully [to a previous critique] and because they think the magazine, which generally opposes regulation, is reporting from a biased point of view," then–Public Editor Margaret Sullivan wrote. "The editors objected to many elements of Mr. Epstein's reporting, including his apparent defense of practices that allow undocumented or illegal immigrants to work in salons."

Biases in any direction (including the Times') are ultimately irrelevant to a truth claim. Were the salons' help-wanted ads in Chinese newspapers translated and portrayed accurately in The New York Times, or not? Sullivan (though not her bosses) eventually conceded: "In places, the two-part investigation went too far in generalizing about an entire industry. Its findings, and the language used to express them, should have been dialed back—in some instances substantially." Oh.

This minor exchange foreshadows a few consistent themes during Baquet's 8-year tenure at the top of journalism's priesthood: the less-than-collegial engagement with criticism, the retreat to invoking noble motives when defending inferior work. (Sullivan praised the paper's "admirable intentions in speaking for underpaid or abused workers"—many of whom, incidentally, were soon out of a job thanks to a Times-inspired state crackdown.) And instead of operating on clearly articulated journalistic or administrative standards, the paper, and especially Baquet, conducted a kind of constantly recalibrating balancing test where smaller transgressions and untruths collided with larger narrative or historical concerns, subjecting difficult publishing and personnel decisions to the transitory passions of an increasingly activist staff.

In these areas Baquet frequently found himself straddling the generational divide in his own newsroom, as the younger cohort demanded the "moral clarity" of describing malevolent actors (usually Republicans) with maximally negative adjectives, helping in the process to push out a series of quality journalists presumed to have retrograde views and workplace manners.

Anguished and Hamlet-like as he was in those moments—I dare you to read all the way to the end of this August 2019 transcript of an all-staff Times meeting mostly about a single headline—Baquet did pull off the political trick of both yielding to and pushing back somewhat against the mob, which (along with some charisma) allowed him to serve out his term all the way to the mandatory Times editor-retirement age of 65. At a time when social upheaval was producing serial defenestrations at senior cultural institutions, Baquet sticks out for surviving.

"Baquet," Politico media columnist Jack Shafer observed this week, "was a masterful politician while in office." Seconded New York's Shawn McCreesh: "Baquet is an operator, a politician who likes being liked."

"Politician" is usually not a journalistic term of endearment, redolent as it is with slipperiness, an eagerness to please, and shifting principle on a dime for purposes of expediency. These tendencies and more contributed to the two main ways Baquet became a handmaiden to journalistic degradations in the 21st century:

1) Acceding to the terrorist's veto. In 2006, when Islamist nutbags started killing people all over the world in stated opposition to a series of Muslim-tweaking cartoons (including some that depicted the Prophet Muhammad) that were first published in Denmark, American news publications were faced with a choice: Do we let readers see the visual basis of this murderous tantrum, or do we cower, either in fear of being attacked or fear of giving offense?

Almost every newspaper and magazine chose fear. (Reason posted the images online.) Dean Baquet back then called shots for the Los Angeles Times, where I was working on the opinion pages (which was overseen by the publisher, not the editor). When media columnist Tim Rutten lobbied to reprint some of the cartoons, he "fully expected the proposal to be rejected, and it was—quickly and in writing, though the note also expressed the hope that the column would be as forceful and candid as possible." Ah, the Hamlet-like straddle. (I lost my own battle to reprint them in the opinion section, though at least the editor there was forthright about being scared.)

That industry-wide act of self-censorship, as predicted, placed an ever-larger target on the few journalistic backs that still contained a spine. The French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, one of the most reliable republishers of the Danish cartoons and mockers of religious zealotry (of all stripes), was firebombed in November 2011 and then massacred in January 2015. The next issue of the beleaguered publication had one of the best covers I have ever seen (and I see it every day, on my wall).

By then, Baquet had had nearly nine years to think about how to approach the visuals in covering this horrific free-speech story. While the crime scene was still being scrubbed of the blood of beloved illustrators, Baquet was quoted at length in an agonized Margaret Sullivan column headlined (generously, in my opinion), "A Close Call for Publication of Charlie Hebdo Cartoons." Watch the politician in action:

Baquet told me that he started out the day Wednesday convinced that The Times should publish the images, both because of their newsworthiness and out of a sense of solidarity with the slain journalists and the right of free expression.

He said he had spent "about half of my day" on the question, seeking out the views of senior editors and reaching out to reporters and editors in some of The Times's international bureaus. They told him they would not feel endangered if The Times reproduced the images, he told me, but he remained concerned about staff safety.

"I sought out a lot of views, and I changed my mind twice," he said. "It had to be my decision alone."

Ultimately, he decided against it, he said, because he had to consider foremost the sensibilities of Times readers, especially its Muslim readers. To many of them, he said, depictions of the prophet Muhammad are sacrilegious—those that are meant to mock even more so. "We have a standard that is long held and that serves us well: that there is a line between gratuitous insult and satire. Most of these are gratuitous insult."

"At what point does news value override our standards?" Mr. Baquet asked. "You would have to show the most incendiary images" from the newspaper—and that was something he deemed unacceptable.

I asked Mr. Baquet about a different approach—something much more moderate, along the lines of what the [Washington] Post's OpEd page did in print. "Something like that is probably so compromised as to become meaningless," he responded, though he was speaking generally, not of The Post's decision.

The Times undoubtedly made a careful and conscientious decision in keeping with its standards.

Bolding mine, for reasons of foreshadowing. The alleged "standard" separating gratuitous insult and satire was immediately shown to have been anything but long-held. The newspaper, like newspapers immemorial, maintained a use/mention distinction when it came to individual pieces of potentially newsworthy art ("use/mention," too, is foreshadowing).

Just one day later, the Times demonstrated how the ever-slippery standard about Islamic imagery in fact did not require insult at all, when it comes to depicting really existing artwork based on really existing historical figures. In an article about how a statue of Mohammad once stood atop a New York courthouse for a half-century without much fuss, the Paper of Record refused to even run a file photograph of the article's subject, saying instead that

the statue was finally removed out of deference to Muslims, to whom depictions of the prophet are an affront.

(For the same reason, The New York Times has chosen not to publish photographs of the statue with this article.)

By the time the post-massacre Charlie Hebdo cover came out, the only question was how agonized and/or annoying Baquet would be in explaining why he wouldn't republish it.

"Actually we have republished some of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons including a caricature of the head of ISIS as well as some political cartoons," he told his own paper in a statement. "We do not normally publish images or other material deliberately intended to offend religious sensibilities. Many Muslims consider publishing images of their prophet innately offensive and we have refrained from doing so."

And a dissenting Margaret Sullivan characterized his decision-making thusly: "Baquet told me repeatedly in recent days that he was paying attention to reader comments on last week's blog post, and that he found them thoughtful and, in many cases, eloquent. He also passed along to me examples of correspondence from readers who thanked him for The Times's restraint and sensitivity last week."

Leaders of American cultural institutions have over the past 16 years invented a publishing taboo applicable to just one of the major religions. (Pope made of condoms? Insult away!). They have enshrined in practice not just a heckler's veto, but a terrorist's veto. It is one of single most shameful developments in the contemporary free-speech biz, and Baquet's fingerprints are all over it.

2) Yielding too much to the newsroom mob. In February 2021, Baquet fired the paper's lead pandemic reporter over an extracurricular linguistic infraction two years prior that the reporter had already been investigated and punished for. The only reason Baquet did so was that the internal report was leaked by someone within the Times to The Daily Beast, sparking a series of histrionic demands from within the newsroom.

Donald McNeil, Jr., had been on a Times-sponsored overseas trip with high school students, one of whom asked him whether he thought another high schooler should have been punished for having been discovered to have made a video at age 12 in which she used the word nigger. "To understand what was in the video," McNeil would write after being forced out of the Times, "I asked if she had called someone else the slur or whether she was rapping or quoting a book title. In asking the question, I used the slur itself."

Parents complained about that and other McNeil behavior they found objectionable on the trip. The Times, through an initial statement last January, said it had "conducted a thorough investigation and disciplined Donald for statements and language that had been inappropriate and inconsistent with our values….We found he had used bad judgment by repeating a racist slur in the context of a conversation about racist language. In addition, we apologized to the students who had participated in the trip." Added Baquet: "[I] concluded his remarks were offensive and that he showed extremely poor judgment, but that it did not appear to me that his intentions were hateful or malicious. I believe that in such cases people should be told they were wrong and given another chance."

This was not nearly punishment enough for at least 150 of McNeil's colleagues, who, declaring themselves "outraged and in pain," countered that McNeil's intentions were "irrelevant" and demanded an apology, a reinvestigation, and an organization-wide study about how racial bias informs newsroom decision-making. They also made the damning allegation that McNeil had demonstrated "bias against people of color in his work and in interactions with colleagues over a period of years."

Remarkably, Baquet and his soon-to-be-replacement Joe Kahn buckled, declaring (falsely) that "We do not tolerate racist language regardless of intent."

Zero-tolerance dismissals over such actions are both illiberal and distressingly common at major cultural institutions. It's a subject that is thankfully still covered well in the pages of The New York Times, by Michael Powell among others. But when practiced by the country's flagship newspaper, to the degree of trying to erase the absolutely crucial use/mention distinction, it accelerates one of the more noxious trends in contemporary intellectual life.

There is a clear and evident internal attempt to squeeze out discordant voices from the Times' venerated pages. To the extent that those efforts continue to succeed, the paper will not only be more politically uniform and less interesting; it will encourage similar agitations throughout the mediasphere. Dean Baquet may have pushed back on occasion—including in his farewell present of restricting staff Twitter use—but he gave enough ground to leave open the question of who really will run that newsroom once a character less politically adept sits in his chair.

If Baquet had an impressive pre-editing résumé—he was a Pulitzer-winning investigative reporter, after all—his successor, Joe Kahn, might have an even more spectacular (if considerably more privileged) pedigree, bootstrapping his reportorial chops in China, learning Mandarin, reorganizing the Times' international coverage, and shaping the paper's ongoing "Live" desk. But judging by an exhaustive New York profile from this week, Kahn lacks Baquet's political skills, either in confidently talking out of both sides of his mouth or in demanding respect and notice on the shop floor.

Reading between the lines of Kahn's public statements, he seems even more eager than Baquet to keep the paper above the right-left fray, to trim back the staff excesses on social media, and to emphasize the paper's hard news mission above the increasingly identity-politics-drenched everything else. He'll be attempting to act on those impulses not as a college-dropout black man and self-made journalist from the South hip enough to interview Jay-Z, but as an old rich white man from Boston with fancy tastes. We will likely soon find out whether The New York Times can be managed by a non-politician.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Coming next week: Dean Baquet is an editor at Reason.

first in the queue "Why Trump Caused the Ukraine Invasion"

Didn't Boehm already write that story?

Sullum did. ENB linked it to the daily roundup.

The unprovoked invasion. Except by Trump of course.

I gotta give credit to Houellebecq, though, if you follow the link under "best covers" and go to the comments and follow the first link to Steyn's blog, you'll see that in the novel he'd just written then, he put Marine Le Pen in the 2022 French election finals. 😀

Very good odds his replacement is at least as much a partisan hack as he is.

"Very good odds his replacement is at least as much a partisan hack as he is."

Most likely the replacement will be worse.

One of the great things about America is that the lessers (whether employees of less entities or downscale commenters) get to nip at the ankles of their betters as much as they like.

You're talking about the Liberal outrage at Elon Musk, right?

I don't think Kirkland is aware of anything beyond his Borg up-link.

And instead of operating on clearly articulated journalistic or administrative standards, the paper, and especially Baquet, conducted a kind of constantly recalibrating balancing test where smaller transgressions and untruths collided with larger narrative or historical concerns, subjecting difficult publishing and personnel decisions to the transitory passions of an increasingly activist staff.

This is important, and the "activist staff" are really ruining journalism. Ruining it.

I'm re-posting this because it's too important, here's Glenn Greenwald describing, in detail how powerful corporate news agencies are no longer concerned with investigating power centers and instead will send "investigative journalists" to the doorsteps of private citizens because of ideological disagreements.

We write a lot of this off dismissively as "wokeness" which is a perfectly fine way to describe the entire activist industry, but the reality is, this 'wokeness' problem is quite insidious and is there by design. The critical theories departments where literally all of this came from explicitly demands an "activist" disposition in all of life's interactions. We got the education we paid for.

What we have is “destructive nihilism”, Nietzsche’s term. Postmodernism’s shitpile is working its magic. When the woke activists have torn down everything, they can have their “year zero”. Led by commandante zero, who’ll see the need for some awesome bloodletting

Also known as "preaching to the choir".

In the age of splintered media, no one subscribes to objective news sources, just sources that confirm their own biases.

Are there any that don't?

I think what we need is biased but honest reporting, like Taibbi and Greenwald. Although that's vanishingly rare too.

Also, it'd be nice if Reason would go back to a libertarian bias, instead of the current bien pensant prog one.

"the Paper of Record still sets the tone for the newspaper industry and prestige journalism, and it is still capable of unmatched reportage, such as its valuable work from Ukraine. "

Does this mean a posthumous Pulitzer for Walter Duranty?

The irony of that line probably never occurred to Welch.

Historical New York Times reporting on Ukraine has reached the level of genocide participation usually only achieved by outlets like Der Stürmer or Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines.

Matt's sensibility seems to have gone the way of your Godwin alarm.

Does the Holodomor qualify for Godwinning?

Um .... HITLER!!!11!!!11!!!

Speaking of which, this is probably an excellent thread to post this in. Ran across this article that does a deep investigative dive into how Hollywood now hires its writers, producers, directors, and general staff for making movies, and it's not pretty.

Some quick hits:

South Park survived by donning its Vice-presidential kneepads and apologizing to Manbearpig

Imagine if these people saw “Even Dwarfs Started Small” by Herzog?

Joe Kahn, might have an even more spectacular (if considerably more privileged) pedigree

From the pictures of him that I've seen, he's also a gay male prostitute. A power bottom, I believe.

What the hell is that picture of him posing on the floor about?

I really don't want to know what that means.

(I lost my own battle to reprint them in the opinion section, though at least the editor there was forthright about being scared.)

This is what I said when this whole controversy came about. What annoyed me was the bullshit careful contortions that the media went through to not print them... when what they should have done was simply said, "Hell no we're not printing these cartoons, these people are fucking nuts and we're terrified of them." but that went against the narrative.

You want to piss off a conservative: Lie to him.

You want to piss of a liberal: Tell him the truth.

When it was announced...reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones would be joining the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, [Dean] Baquet said, “Nikole Hannah-Jones is one of the finest journalists of her generation, the rare mix of major investigative reporter and big-voiced writer.”

If that isn't the voice of a bloviating hack with delusions of grandeur I don't know what is.

Khaaaaaaaannnnn!

American Journalism's Most Successful Politician To Step Down From Ruining The New York Times

FTFY

America's best paper used to be the Wall Street Journal, but it's all pay-walled now so who's to say?

I'd probably go with the New York Post since they aren't afraid to report actual news.

Bezos uses it to suck up to the DC establishment and that's about it. Good if you're looking for a paper to speak power to truth. An outlet that sticks up for the big guy.

What does Bezos have to do with the Wall Street Journal or the New York Post?

I want daily hard news from somebody, so I pay the Journal sub. So far it's been worth the cost.

The idea that the editors of Reason think that they stand on anything like equal footing with the NYTimes, to be able to lob a critique and have it responded to, is hilarious.

Most of the pieces I deign to read on this site are written with the sophistication you'd expect from an op-ed farted out by a college student writing for their campus paper - bracketing as a category to themselves the pieces that clearly express the views of a certain set of oil and gas industry executives, which are just plain misinformation. I would never rely on this site for straight "news," and the only reason I read it at all is that I'd like to keep abreast of the latest right-wing talking points so I can be attuned to them when they pop up in the genuine news I do consume.

And this piece - Christ. Did you have to spend so much time to dredge up... just two examples to hook a complaint on? If we were to judge Reason by the standards we'd apply to the NYTimes, this op-ed would be labeled unprofessionally self-indulgent and vapid.

Most of the pieces I deign to read on this site are written with the sophistication you'd expect from an op-ed farted out by a college student writing for their campus paper

Ironically, this can describe the New York Times.

Not at all: NYT pieces are professionally written: by propagandists and psyop experts.

No they're not. They're written by some trash Millennial journalism school grad that's been pushed up based solely on their skin color or genitalia shape.

The millennials provide trashy filler in between the propaganda and psyop crap.

Hear hear. Haughtiness is the proper response to such presumptuous insolence!

You 'deign' to read. Good for you, and you got the pathetic smear about right-wingers in at the same time. Time for a nap before some light bullying of folks that disagree w/ your views, one can guess.

Well, Reason has its problems to be sure, but they'll never be as low as the Duranty News. The NYT has a tradition of mendacity in the service of totalitarianism that is unmatched outside of the official propaganda outlets of the former Soviet bloc.

-jcr

Whereas most of the pieces one reads in the NYT are straight materials from government sources and politicians, designed to manipulate the public, created by experienced propagandists, public relations experts, and psyop specialists.

That is, NYT articles look highly professional to you because they were indeed created by professionals, just not the kind of professionals that deserve the title "journalist" as the term "journalist" used to be understood.

"The idea that the editors of Reason think that they stand on anything like equal footing with the NYTimes, to be able to lob a critique and have it responded to, is hilarious..."

The idea that a lying lefty pile of shit like you should be taken seriously regarding anything at all is simply unbelieveable.

Fuck off and die, asshole.

Welch manages to omit the, recorded by NYT staff, editorial staff meeting in which baquet states that the russia hoax has not been effective, the new framing for stories on trump will be racism. He also omits that baquet clearly stated that he did not think that objectively presenting news on topics that the journalist or media outlet had a sociopolitical belief about was their job. In fact, he made it quite clear with his 'sophisticated true objectivity' horseshit and tenure at the NYT that he supports exactly the opposite, a subjective presentation to preserve and present a narrative. Baquet is a hypocrite at best, an authoritarian propagandist is more than fair. The sooner he is compost, the better.

Yeah. I'm glad to see more news outlets exposed for the way they do business. The New York Times, Washington Post etc. deserve to be scrutinized the same way 60 Minutes scrutinizes Dupont, Dow Chemical, Lumber Liquidators etc. These are massive corporate machines and they deserve the same type of whistle-blowing, internal memo-leaking, hidden-camera interview focus as any other "dark shadowy corporation". They believed they were different because they convinced themselves that they're no more than saintly truth-tellers, speaking truth to power. But they're not, they're just another shadowy corporation that runs on self-interested motives.

You forgot one. At least.

https://reason.com/2020/04/14/tara-reade-joe-biden-dean-baquet-new-york-times-sexual-assault/

Why would a Democratic Party house organ break off an attack on the enemy to cover something potentially damaging to its bosses?

He called the NYT "unpersuasive" on its explanation for covering up rape accusations; wow, that's harsh criticism!

My takeaway from this article is that he's a lefturd piece of shit.

-jcr

Reason discovers that the NYT no longer does honest journalism and shamelessly promotes woke ideology. Now do Reason. There is not a single Reason "editor" willing to diverge from the proscribed narrative whether it be Trump, Covid vaccines, BLM or anything else. Food trucks notwithstanding. Maybe the next podcast will include a single individual who makes the case that leftist tyranny is a greater threat to liberty than Libsontiktok. Not holding my breath.

Getting in bed with socialists to spew their propaganda will do that... up to a point.

Spewing neocon propaganda apparently is now "valuable work from Ukraine".

I wonder whether the death toll this time around will be even higher than last time the NYT conducted "valuable work from Ukraine".

"Baquet did pull off the political trick of both yielding to and pushing back somewhat against the mob"

I guess it was at least 35 years ago I dropped the NYT. They did not match headlines with story content. Often the meat of the article would be buried on C8ish that contradicted the bias headline. Still hard to avoid its influence.

I dropped the NYT about two decades ago; I figured that if their reporting on subjects I knew about was such garbage, it was likely garbage on everything else as well.

I credit the NYT and their piss-poor reporting with being the catalyst for me leaving behind progressivism and American-style liberalism (both of which were far less toxic back then than they are now).

"...I would argue the best investigative paper, [...] it's getting Trump's taxes…"

Almost as informative as opening Al Capone's vault.

Dean Baquet: How the Fourth Estate Became the Fifth Column.

Is that your new book coming out?

Great article. Thanks mate!

https://alo-case.com/