Can a Spending Rider Save a Medical Marijuana Supplier From Prison Seven Years After He Was Convicted?

Two congressmen rebuke the DOJ for breaking the law by continuing to pursue such cases.

Last December, after Congress approved a spending bill that told the Justice Department to refrain from interfering with the implementation of state medical marijuana laws, I wondered whether that provision would actually block federal prosecution of patients and their suppliers. Federal courts are beginning to address that question. In February a federal judge in Spokane, Washington, rejected claims that the amendment, which was sponsored by Reps. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Calif.) and Sam Farr (D-Calif.), barred continued prosecution of the Kettle Falls Five, patients whom the government potrayed as marijuana merchants (a charge the jury ultimately rejected). Now federal prosecutors in California are seeking a similar ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit.

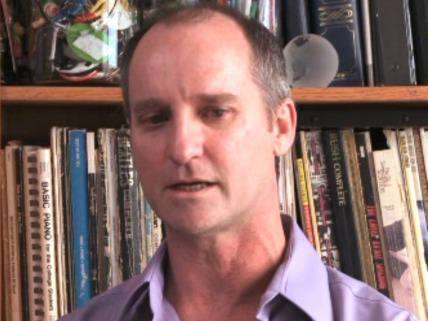

The California case involves Charlie Lynch, who operated a medical marijuana dispensary in Morro Bay until the feds raided the place in 2007. Lynch was convicted of five federal felonies in 2008 and received a one-year prison sentence in 2009, based on a sympathetic judge's debatable interpretation of the criteria for the "safety valve" that lets certain drug offenders escape mandatory minimum sentences. Prosecutors want the appeals court to overturn that sentence in favor of a five-year term. Lynch remains free on bail as he appeals his conviction, and the Rohrabacher-Farr amendment gave him a new argument: By persisting in their effort to put him behind bars, federal prosecutors are violating a congressional command barring the Justice Department from spending money to "prevent" states from "implementing" their medical marijuana laws.

"If federal prosecutors are engaged in legal action against those involved with medical marijuana in a state that has made it legal," Rohrabacher tells The New York Times, "then they are the ones who are the lawbreakers." If the 9th Circuit accepts that argument, says Ohio State law professor Douglas Berman, who presides over the the Marijuana Law, Policy & Reform blog, "this will be huge."

The Justice Department argues that enforcing federal law does not prevent states from implementing medical exceptions to their own penalties for marijuana-related activities. Yet the feds do seem to be second-guessing state officials' interpretation of state law, which is a crucial part of implementation. In both the Washington and California cases, the defendants were not allowed to talk about medical use of marijuana in front of the jury, since the plant is banned for all purposes under federal law. Prosecutors, partly in response to a DOJ policy that frowns on targeting people who comply with state marijuana laws, nevertheless have maintained that the defendants failed to do so. Local and state officials apparently did not see it that way, since neither Lynch nor the Kettle Falls Five were charged with crimes under state law.

Last week a Justice Department spokesman said actions against individuals such as Lynch or organizations such as the Harborside Health Center in Oakland are unaffected by the Rohrabacher-Farr rider, which applies only to steps aimed at "impeding the ability of states to carry out their medical marijuana laws." According to this reading of the amendment, it bars a DOJ lawsuit seeking to overturn a state's medical marijuana law, but it allows raids that shut down every dispensary and tear up every patient's garden.

Judging from the debate that preceded the House vote on the rider, that is not the outcome that legislators envisioned. Here is the gloss that Farr offered:

This [amendment] is essentially saying, look, if you are following state law, you are a legal resident doing your business under state law, the feds can't come in and bust you and bust the doctors and bust the patient. This doesn't affect one law, just lists the states that have already legalized it only for medical purposes, and says, "Federal government, you can't bust people."

Other supporters of the measure agreed, and so did opponents. Rep. Andy Harris (R-Md.) wondered, "How is the DEA going to enforce anything when, under this amendment, they are prohibited from going into that person's house growing as many plants as they want, because that is legal under the medical marijuana part of the law?" Rep. John Fleming (R-La.) complained that the amendment would "make it difficult, if not impossible, for the DEA and the Department of Justice to enforce the law." Now the Justice Department is claiming, to the contrary, that the amendment has no effect at all on its ability to enforce the law.

"No reasonable person would agree with the department's interpretation of the amendment," Farr says in a statement issued today. "The DOJ can try to parse its wording, but Congress was perfectly clear: Stop wasting limited funds attacking medical marijuana patients."

Farr and Rohrabacher try to set the record straight in a letter they sent to Attorney General Holder today:

As the authors of the provision in question we write to inform you that this interpretation of our amendment is emphatically wrong. Rest assured, the purpose of our amendment was to prevent the Department from wasting its limited law enforcement resources on prosecutions and asset forfeiture actions against medical marijuana patients and providers, including businesses that operate legally under state law….

We can imagine few more efficient and effective ways of "impeding the ability of states to carry out their medical marijuana laws" than prosecuting individuals and organizations acting in accordance with those laws….

We respectfully insist that you bring your Department back into compliance with federal law by ceasing marijuana prosecutions and forfeiture actions against those acting in accordance with state medical marijuana laws.

Reason TV on the Lynch case:

Show Comments (18)