California's Unlikely Pot Crackdown

Scenes from the federal clampdown on medical marijuana in the Golden State after Proposition 19.

On October 7, 2011, anxious medical marijuana advocates and patients arrived early in the diamond-patterned granite plaza of the Robert T. Matsui United States Courthouse in Sacramento. On the 10th floor of the federal building there, representatives of California's four United States attorneys were meticulously checking credentials, refusing to admit anyone without an up-to-date press pass. A day earlier, the state's top federal prosecutors had announced that they were about to issue a joint statement on the sale, distribution, and cultivation of marijuana. There was a pervasive sense that something seismic was about to take place.

Demonstrators outside the federal building were waving signs at passing traffic with messages like "Closing Collectives Harms Patients," and "By Legal Democratic Vote, Cannabis Is Medicine." Protesters chanted "We're healers! Not dealers!" Advocates had been faxing each other recent letters sent by U.S. attorneys to scores of California dispensaries threatening federal property seizures if the establishments didn't stop selling marijuana within 45 days.

One such letter, directed at the state's longest-operating dispensary, the Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana (which opened in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Fairfax even before the 1996 passage of the landmark medical marijuana initiative Proposition 215), threatened the alliance's landlord with prolonged prison time for dealing drugs within a thousand feet of a Little League field. "Violation of the federal law referenced above is a felony crime," the missive read, "and carries with it a penalty of up to 40 years in prison." Less than a year after California came close to legalizing recreational marijuana for all adults, the state was ground zero for a vast new federal crackdown.

Run-up to a Crackdown

The Sacramento press conference was being hosted by local U.S. Attorney Benjamin Wagner, the first top California prosecutor appointed by President Barack Obama (in November 2009). Wagner had come into the position after spending nearly a decade as chief of the FBI's Special Prosecution Unit, targeting public corruption and financial and corporate fraud. He would later say that he hoped to be known as the prosecutor who cracked down on mortgage fraudsters, not the guy who "launch[ed] a campaign against medical marijuana."

But Wagner, whose district spanned from the lower Central Valley to the Oregon and Nevada borders, quickly came to see in medical marijuana a similar con game to the one ravaging housing markets in cities like Stockton. Providing cannabis for sick people, he thought, was "a fig leaf" for big-money enterprises that couldn't care less about personal health.

Wagner's office was in the process of prosecuting an L.A. attorney and an Oakland cannabis businessman for allegedly luring two small-town tomato growers into registering as medical marijuana patients in order to lease their greenhouses for marijuana cultivation. He had seen pot farmers amassing medical recommendations for California patients and then trafficking marijuana out of state. There were shady investment schemes, and cash-heavy transactions involving people who "know nothing about treating glaucoma and cancer."

One week after California voters defeated Proposition 19 by a vote of 54 percent to 46 percent in November 2010, Wagner took part in a previously scheduled meeting at the Sacramento offices of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), where fellow U.S. attorneys and midlevel Justice Department officials strategized with the DEA about how to better coordinate a response to California's burgeoning medical marijuana industry. A draft letter from Deputy Attorney General James Cole that Wagner had helped prepare prior to the meeting declaratively spelled out the government's opposition to commercial cannabis operations. It dispelled any notion that a 2009 federal memo-saying the Justice Department wouldn't target individuals complying with state medical marijuana laws-was intended as a green light for a marijuana industry green rush. Cole said the earlier memo only meant the government wouldn't focus resources on individual medical cannabis patients or their caregivers. On June 29, 2011, he declared, "The term 'caregiver' as used in the memorandum meant just that: individuals providing care to individuals with cancer or other serious illness, not commercial operations cultivating, selling or distributing marijuana."

In the months leading up to Cole's declaration, Wagner had done his part, letting the DOJ know that "federal law is totally being flouted here in California and we have to respond." Weeks before the Sacramento announcement, he informed his superiors that California's U.S. attorneys were going to initiate sweeping and continuous actions against purported medical marijuana profiteers. Obama's Justice Department signed off on the plan.

As reporters and camera crews crowded the 10th-floor conference room, Wagner cut to the chase. "We are targeting money-making commercial growers and distributors who use the trappings of state law as cover," he said. "Today, we put to rest the notion that large marijuana businesses can shelter themselves under state law and operate freely without fear of federal enforcement."

Andre Birotte Jr., the U.S. attorney in Los Angeles appointed by President Obama in March 2010, held aloft a pot magazine, Mota, that featured on its cover a marijuana leaf and reams of cash. This wasn't about "backyard grows with small amounts of marijuana for use by seriously ill people," as Wagner said, but rather what Birotte called a "new California Gold Rush" that violated both state and federal law.

The assembled prosecutors announced a handful of new indictments, and warned of forfeiture actions against dozens of dispensaries. The enduring sound bite was delivered by Melinda Haag, the U.S. attorney in San Francisco who had been appointed by Obama in August 2010. Haag, a veteran trial lawyer and federal prosecutor who had specialized in white-collar crime, environmental abuses, civil rights offenses, and child exploitation, presided in the Northern District of California, where the modern medical marijuana movement was born and largely headquartered.

"The California Compassionate Use Act was intended to help seriously ill people," said the University of California, Berkeley, law school grad, with a steely gaze. "But the law has been hijacked by profiteers who are motivated not by compassion but by money."

Haag announced that she was immediately targeting dispensaries "that sell marijuana very close to schools, parks and other places where children learn and play," and threatening landlords and lienholders with property seizures and federal prison time if they didn't cease sales of marijuana "in close proximity to children…[,to] playgrounds and schools and Little League fields." Pointedly, it was the U.S. attorney in the state's most liberal federal district, and cradle of marijuana activism, who symbolized the determination of the Obama administration appointees to crack down hard on California's cannabis commerce.

'Please Don't Shoot the Dogs'

Over the ensuing weeks and months in Haag's district, agents for the DEA, the IRS, and the U.S. Marshals Service went after the icons of California's marijuana movement. Just six days after the announcement, an armored-vehicle caravan carrying heavily armed DEA agents in camouflage rumbled over winding roads in southern Mendocino County, passing vineyards and grazing cattle, barreling beyond a gate marked "Member, Mendocino Farm Bureau." The agents then arrived, with a battering ram, to the country home and front door of Matt Cohen. "You don't have to knock it down," Cohen pleaded. "I'll open it. And please don't shoot the dogs."

Cohen had been Mendocino's poster boy for creating an open, highly regulated medical marijuana regime. He had worked with Mendocino supervisors and the sheriff to establish Ordinance 9.31, a system allowing confirmed growers with working contracts to cultivate up to 99 plants, which were tagged with zip ties and regularly inspected by the sheriff's department.

The Mendocino cannabis accord brought Cohen and the sheriff, Tom Allman, national attention on Frontline. Four weeks before DEA agents arrived at his house, a county supervisor and sheriff's sergeant had testified in neighboring Sonoma County on behalf of two of Cohen's drivers, who had been arrested while driving his Northstone Organics "farm direct" marijuana to people who had medical recommendations.

As he was pressed against an exterior wall and handcuffed outside his door, Cohen tried to impress upon the federal agents that he was a locally approved, regulated, and supervised cannabis grower. "It's a sham," one of the agents answered. Crews with chainsaws hacked down the 99 plants in his fenced, video-monitored garden.

No federal criminal charges followed, and local charges were later dropped against Cohen's drivers. But the federal raid put Cohen out of business, bigfooted the Mendocino County sheriff, and frightened the Board of Supervisors into repealing the county's tagging and oversight program. "I think Matt Cohen's reputation as a cooperative operator snowballed into somebody at the federal level saying we need to make an example of this guy," Sheriff Allman charged.

Two weeks after the raid, medical marijuana advocates and a sympathetic state lawmaker gathered in a San Francisco hotel conference room near where President Obama was due to appear at a fundraiser. California's dispensaries were already closing down right and left. The federal government was pursuing a forfeiture suit against the Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana, which would soon surrender and close its doors. The movement-revered Berkeley Patients Group dispensary was threatened with property seizure and prosecution for distributing medical marijuana within a thousand feet of a French language school and a school for the deaf, and would soon also shut down. (It would later reopen at a new location, only to be targeted again in a 2013 federal forfeiture lawsuit.)

As worry and anger consumed the October 24, 2011, gathering, San Francisco Assemblyman Tom Ammiano opened the press conference by saying, "Everybody take a deep breath. Everybody inhale." He paused, and then continued: "Look, this is getting a little Kafkaesque for my blood."

"They stated they were conducting this campaign because California's medical marijuana law had been hijacked by profiteers," complained Steve DeAngelo of Oakland's Harborside Health Center, the heralded cannabis provider that famously billed itself as the biggest marijuana dispensary in the world. But the government, he said, was going after organizations that were "one hundred percent compliant and have not diverted medical marijuana anywhere."

Harborside was facing a $2.4-million tax-deficiency demand from the IRS on its 2007 and 2008 federal tax returns, with an ongoing audit targeting subsequent tax years. Under IRS Section 280E, a little-known tax code approved by Congress in 1982 to prevent illegal drug dealers from deducting business expenses, the agency was refusing to let Harborside take tax deductions for executive and employee salaries, patient services (ranging from counseling to chiropractic care), utility payments, rent, and other expenses available to non-marijuana health firms. So even though Harborside was one of Oakland's largest taxpayers (paying $1.1 million in local medical marijuana taxes, and $2 million in state taxes), the IRS was using tax law to try and shut the service down.

In a later speech at the Sacramento federal courthouse, where the sweeping actions had been announced, DeAngelo added this crescendo: "We want to know, Mr. Holder. We want to know, U.S. attorneys. How many more need to suffer before you do the decent thing and surrender this campaign of terror and intimidation?"

'I'm Not a Drug Dealer. And I Don't Sell to Kids.'

In cities and counties that had long fought the presence of marijuana dispensaries, the federal crackdown was a welcome development. For nearly two years, code enforcement officers in Sacramento County had sent out nuisance abatement notices, levied fines, and gone to court to close marijuana stores that county supervisors said weren't permitted under local zoning laws. Despite those efforts, the number of marijuana stores surged, from a dozen to nearly a hundred.

But as landlords received threats from the feds, the dispensaries virtually disappeared in a matter of weeks. One of the last holdouts, the Magnolia Wellness Center in the community of Orangevale, went out with a flourish, offering free grams of marijuana and heavy discounts on strains ranging from Lemon Wreck to Violator Kush. A queue of hundreds of people, from feeble patients in wheelchairs to college kids with a bounce in their step, encircled the building like a Depression era breadline.

Lino Catabran, who went from running a waterbed warehouse to selling Porsches and, later, recreational vehicles before converting his Sacramento dealership into a marijuana store, saw the writing on the wall when federal authorities seized his bank account. A criminal complaint charged that his One Love Wellness dispensary illegally structured deposits in amounts under $10,000 to avoid IRS reporting requirements. Catabran closed the dispensary with a New Year's Eve party, advertised under the headline "Feds Closing Sacramento Collectives."

San Diego City Attorney Jan Goldsmith, who had long had his sights on dispensaries, called the federal asset forfeiture threats "a devastating tool." Within months, nearly 200 city dispensaries would close.

The preferred enforcement tactic of U.S. Attorney Melinda Haag proved maddening to operators in the densely packed urban tapestry of San Francisco. Haag's pronouncement that she would protect children by targeting medical marijuana sales near parks and schools led to a forfeiture order against the Divinity Tree dispensary in the city's Tenderloin District because it was within one thousand feet of a playground.

But the dispensary was on a different street, and out of view of the swings and wooden climbing train of tiny Sgt. John Macaulay Park. Directly across from the street-corner playground was a strip club with flashing lights advertising "Live Nude Shows." People walking around the block to the dispensary would encounter a massage parlor, a porn theater, four liquor stores, and a tobacco and head shop. But none of those were against federal law. Operators Charlie Pappas, a quadriplegic after being shot during a robbery three decades earlier, and fellow medical marijuana advocate Raymond Gamley closed the Divinity Tree rather than face the wrath of the feds. "I can't tell you how bad it feels, what they did to us," Gamley said. There was virtually no place in San Francisco that wasn't within a thousand feet of some sensitive use that would offend the government.

Catherine Smith, a former Bangor, Maine, police officer who ran the HopeNet Co-op dispensary south of San Francisco's Market Street, refused to close just because, three years earlier, a private Mandarin immersion school for youths opened blocks from her establishment. Inside one of the few city dispensaries that allowed patients to smoke marijuana on-site, Smith seethed in the aromatic air: "I'm not a drug dealer. I'm permitted and regulated. It seems to me California voted for this overwhelmingly. And I don't sell to kids."

The dispensary displayed a framed letter from former San Francisco District Attorney Kamala Harris, now California's attorney general. It read, "My office will not compromise in supporting the rights for our loved ones who are sick and need medical marijuana." But within a few months, Smith and operators of another San Francisco dispensary, the Vapor Room, surrendered in spectacular fashion. They created a funeral procession to the federal building with a blaring brass band, coffins adorned with "Marijuana Is Medicine" signs, and a marching 12-foot puppet in the likeness of Melinda Haag.

'This Is Not About Justice. This Is About Revenge.'

Oakland declared itself unfazed by federal actions against its pot shops. In 2012, the city granted four new dispensary permits in hopes of bringing in another $1.7 million of marijuana tax revenue. "The expansion of the medical cannabis permits is a natural extension…to provide patients suffering from serious illness and pain with a safe and reliable source of medical marijuana," proclaimed Mayor Jean Quan. "I am proud that Oakland has long been at the forefront of the compassionate movement."

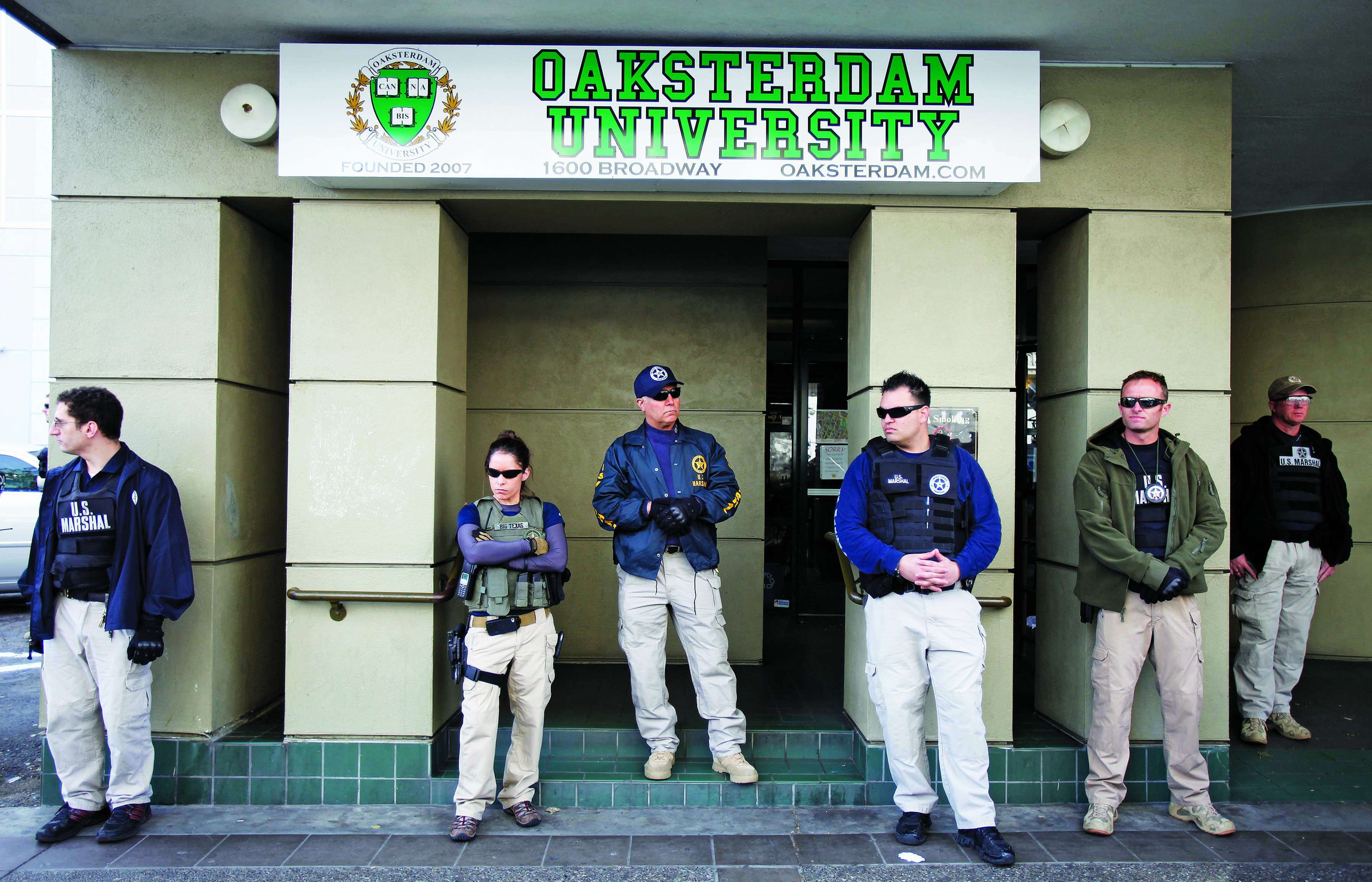

Still, at 6:30 a.m. on April 2, 2012, agents from the DEA, the IRS, and the U.S. Marshals Service entered an apartment building overlooking Oakland's Lake Merritt, ascended to a third-floor apartment, and started shouting at Richard Lee.

This was no ordinary suspect. Lee was president of Oaksterdam University, the first institute of learning dedicated to all things marijuana, and chief funder and architect of Proposition 19. Lee pushed himself out of bed and into his wheelchair. He recalled the instructions of attorneys who had lectured at Oaksterdam: Don't let the cops in-that can be seen as consenting to a search by officers who may not have a warrant. So Lee waited for the federal officers to break down his door, and greeted them after they burst in.

The agents, serving five search warrants, demanded keys for the university and the storefronts he leased, including the Coffee Shop Blue Sky dispensary. Lee had only recently moved the dispensary after a letter from U.S. Attorney Haag warned of its proximity to a school that had opened years after he did.

Lee asked the federal agents in his apartment if he were under arrest. They told him no. At least, he recalled, "they were pretty nice about it and weren't trashing the place and throwing things around."

But reaction on the streets of Oakland was angrier as word of the raid spread and federal agents swarmed into Oaksterdam University and the Oaksterdam Blue Sky dispensary. They handcuffed university employees, broke doors, and hauled out instructional marijuana plants marked with stickers calling for jury nullification in marijuana cases. An angry crowd gathered on Broadway outside the school. Protesters screamed at flak-jacketed federal agents who blocked the entrance to the Princeton of Pot. Agents hauled out a safe containing nearly $100,000-including $90,000 Lee had set aside to pay medical marijuana taxes and licensing fees to the city of Oakland. Finally, the agents stripped bare the Oaksterdam nursery, taking Lee's beloved mother plants used to clone designer cannabis strains. People in the street screamed, "Shame on you!" "DEA go away!" and "Fuck the DEA!"

Steve DeAngelo delivered a sidewalk message to the media. "It's not a coincidence they went after Richard," he said. "They are trying to silence him.…The federal government has turned against the lead organizer and fundraiser for Proposition 19, which very nearly legalized cannabis in the state of California. This is not about justice. This is about revenge."

Nate Bradley, a former police officer from the Central Valley town of Wheatland who had joined the Proposition 19 campaign as a spokesman for the group Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, took a loudspeaker to berate the federal officers who stared back through dark sunglasses. "Anyone who is seen here today is an embarrassment to anyone who ever wore the badge," Bradley declared, growing hoarse with the effort. "This is an embarrassment! You guys are standing here when there are people being kidnapped, when there are crimes to be investigated. And you're standing here threatening somebody for a ground-up herb!"

Richard Lee, who had watched the unfolding raids and street drama on television from his apartment, went to retrieve his mail that afternoon. There was a letter from the civil division of the IRS. It was to confirm a meeting at the end of the month to discuss resolving his tax debt. He read it incredulously. "It was like they were reaching out and shaking your hand with one hand," Lee thought, "and then punching you in the face with the other." Days later, Lee announced he was liquidating his cannabis businesses. He was giving up the Blue Sky dispensary and resigning as president of Oaksterdam University.

'The Arc of the Moral Universe…Bends Toward Justice.'

Tom Ammiano, the San Francisco state assembly member, went to see U.S. Attorney Haag, to find out what kind of state legislation regulating the medical marijuana industry might satisfy the feds enough to ease the crackdown. He came away frustrated. When asked directly, Haag and the other U.S. attorneys were not willing to guide California lawmakers on how to best violate federal marijuana law.

Yet Colorado, with its heavily regulated cannabis industry, with state-licensed marijuana workers, with a state medical-cannabis-policing agency and video surveillance of cultivation, transportation, and sales, wasn't drawing anywhere near the heat that California was. John Walsh, Colorado's U.S. attorney, sent a few dozen letters to dispensaries operating near schools; many merely moved and reopened with neither fear nor recrimination.

Marijuana advocates came up with a regulation plan for California that seemed determined to satisfy every movement constituency, but abandoned the initiative effort after they couldn't get sufficient financial pledges from national drug policy groups or California medical marijuana operators to fund a signature drive.

So Ammiano introduced Assembly Bill 2312, to create a nine-member oversight commission, weighted toward cannabis interests, that would impose licensing fees on marijuana businesses and create a pot policing agency. The bill included none of Colorado's strict provisions; Ammiano and marijuana advocates wanted the new medical cannabis commission to set the rules.

Anxious Democrats, many from communities that had been overrun with dispensaries, did not embrace the bill, and Republicans were eager to ridicule it when it reached the assembly floor. "People want to preserve the chaos and confusion to say that medical marijuana has failed or is a sham," Ammiano told the body. Although he got the bill through the Assembly with a bare minimum majority of all Democrats, Ammiano couldn't muster enough votes to bring medical marijuana regulation to the senate floor.

Meanwhile the federal crackdown continued apace. On Monday, July 9, 2012, employees at Harborside Health Center in Oakland-the largest medical marijuana distributor in the country-and its sister dispensary in San Jose arrived to find posted notices informing them that U.S. Attorney Haag filed civil lawsuits to seize their assets. Harborside wasn't anywhere near places where children gathered, but "I now find the need to consider actions regarding marijuana superstores such as Harborside," Haag explained in a statement. "The larger the operation, the greater the likelihood that there will be abuse of the state's medical marijuana laws, and marijuana in the hands of individuals who do not have a demonstrated medical need."

But then Harborside refused to close. On October 20, 2012, the City of Oakland sued Attorney General Eric Holder, Melinda Haag, and the United States Justice Department to stop the forfeiture action. "This property is vital to the safe and affordable distribution of medical cannabis to patients suffering from chronic and acute pain, life threatening and severe illnesses, diseases and injuries," the city declared. "Oakland has a broad public interest in promoting the health, safety and welfare of its citizens, in protecting the regulatory framework it adopted in compliance with the laws of the State of California."

While the lawsuit works its way through the court system, the Harborside dispensary remains open, assets unseized until the federal government can prove its case. Two weeks after Oakland fought back, the national conversation about pot changed irrevocably, as voters in Colorado and Washington approved legalizing it for all adults, regardless of medical condition. A majority of Californians now tell pollsters that they favor outright legalization, and a state ballot initiative is expected in 2016.

On August 29, 2013, the United States Justice Department offered nuanced-yet potentially landmark-terms of concession. In a new memo, Deputy Attorney General Cole suggested the feds wouldn't intervene in states legalizing pot, either for medicinal or pleasurable pursuits, if those states enacted "robust controls" regulating marijuana sales and distribution. Still the feds aren't surrendering on pot. The Cole memo directs U.S. attorneys to target operations using the cover of any state marijuana laws to traffic into illicit markets, to minors, or into states where cannabis remains illegal. Criminal prosecutions from the federal raids in California continue. The government presses on in civil actions to close the Harborside Health Center.

In the throes of California's pot crackdown, dispensary operator Steve DeAngelo took to quoting Martin Luther King's famous invocation that "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice." Now that full legalization is within reach, DeAngelo is optimistic that the arc is bending favorably for the planet's largest marijuana dispensary.

Peter Hecht is a senior writer at The Sacramento Bee and the author of Weed Land: Inside America's Marijuana Epicenter and How Pot Went Legit (University of California Press), from which this article is adapted.

Correction: This article originally identified San Diego City Attorney Jan Goldsmith as a woman. He is a man.

Show Comments (1)