3 Ways to Get More Americans Into Banking (That Don't Involve the U.S. Postal Service)

Policymakers should get out of the way and let entrepreneurs offer financial services that fit the needs of low-income Americans.

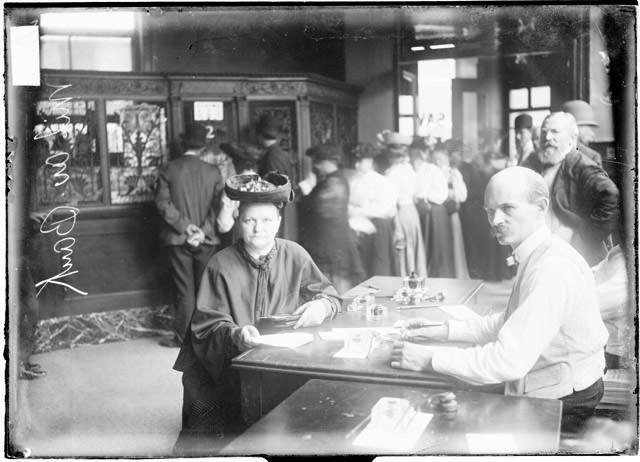

When I was a kid, my father went to Chemical Bank every other Friday to deposit his paycheck, which involved walking to a branch, getting in line, and talking to an actual person. My parents kept a stack of twenties in the silverware drawer so they'd have enough cash in between trips to the teller. I remember the smell of the ink on the carbon copy deposit slips, which I would doodle on and sniff while my mother waited in line at our local branch.

Going to the bank—once a ritual of American life—is going the way of twisting rabbit ears into sharp angles to make the TV more watchable. I've never balanced a checkbook. I take cash out (usually en route to the place where I plan to spend it) at one of the ATMs that's on every block in New York City. My paycheck transfers automatically into my account and I deposit checks by snapping photos of them with my iPhone. I got a mortgage last year without ever stepping into a bank. And I'm hardly alone: A 2013 Federal Reserve survey found that a quarter of U.S. adults used mobile banking services in the last year, and that share is expanding rapidly.

By doing away with the need to wait in line and schedule visits around their limited hours, banks have become a lot less like…the post office. So why would it make sense for the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to get involved in the banking business?

The USPS inspector general released a white paper last month arguing that the organization should use its enormous reach—31,272 retail branches—to do just that. Total mail volume has been shrinking on average five percent a year since 2006 and the USPS is drowning in red ink. However, according to the inspector general, the primary goal isn't the survival of the organization but rather helping the "underserved." The report estimates that about 31 percent of U.S. households don't take advantage of traditional banking services, and they spend on average $2,412 yearly on "alternative financial services," like check cashing and payday lending. In The Huffington Post, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) expressed enthusiasm for the idea, promising threatening that "this is an issue I'm going to spend a lot of time working on."

Post office banking is actually an old idea. The USPS offered savings accounts from 1911 to 1967, which paid an anemic interest rate but were popular with cautious savers because they were backed by the U.S. Treasury. But in 1934, the federal government started insuring the balances on all private bank accounts, and as FDIC limits grew Americans dumped their postal savings accounts. By 1965, two years before the system was dissolved, there were just a million depositors with a total balance of $416 million.

If the organization couldn't compete with private banks before the days of mobile banking, why would it be able to grab market share now? Commercial banks are becoming increasingly nimble in an effort to cut costs, making it harder than ever for a federal bureaucracy with an enormous overhead to have a fighting chance.

Vastly reducing the number of unbanked Americans is a worthwhile goal—and one that could be more easily achieved if Sen. Warren and other Washington do-gooders would abandon their backward-looking schemes and get out of the way. Here are three policies that would truly lead more Americans to get into banking:

1. Eliminate price controls by repealing the Durbin Amendment.

According to a 2012 survey by Bankrate.com, only 39 percent of banks offered free checking accounts, down from 76 percent two years earlier. The average monthly cost of maintaining a checking account doubled between 2010 and 2012, to about $5.50 per month. And customers with low balances generally pay steep out-of-network ATM and overdraft fees. Is it any wonder so many U.S. households prefer to keep their money in cash?

The rising cost of banking is an unintended consequence of the government's effort to knock down transaction costs by decree. Banks once collected about 44 cents every time customers swiped their debit cards at the cash register. With debit card use soaring (surpassing credit cards in popularity in 2006), swipe fees became an enormous source of revenue. Banks responded by dropping checking account fees to get their plastic in as many wallets as possible.

An amendment to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, introduced by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), imposed a price cap that reduced debit card swipe fee down to 24 cents. As a result, banks earned $7.3 billion less in revenue from debit cards swipes in 2012 over the prior year. Predictably, banks responded by jacking their checking account fees and refocusing their efforts on signing up wealthy (and more profitable) customers. If the Durbin Amendment were repealed, most banks would likely go back to offering free checking accounts and otherwise courting the business of low-income Americans.

2. "Savings with a Thrill:" Let banks run lotteries.

When I opened my first savings account in 1990, the interest rate was about 5 percent, meaning I could earn $50 a year on a balance of $1,000. Today, the average money market account pays an annual return of 0.41 percent, yielding just $4.10 per year on that $1,000 balance. But what if banks took that trickle of money and entered it in a lottery to give account holders a small chance at earning some real dough?

Prize-Linked Savings (PLS), the industry term for attaching a lottery to a bank account, is a proven way to encourage saving. A 2010 National Bureau of Economic Research paper traced this idea back to seventh-century England. More recently, PLS accounts have been offered in Latin America, Spain, Germany, Indonesia, and Japan. After World War II, the U.K. introduced saving bonds with award incentives, advertising them as "Savings with a Thrill!"

It's no wonder so many folks are enticed by even the remote possibility of a big payday. Melissa Kearney, a University of Maryland economist and an expert on PLS, told PBS' Newshour: "It's often thought that people are irrational when they play the lottery, but I would challenge that assumption. If you're a low-income individual, how else can you potentially win enough to buy a house or really change your life?"

PLS is prohibited in the U.S. by several federal and state laws that enforce the government's monopoly on running lotteries. But thanks to legislative carve-outs, credit unions in Washington state, North Carolina, Michigan, and Nebraska have adopted a PLS program called "Save To Win." In Washington, savers get a shot at winning a $5,000 prize and multiple other cash awards for every $25 they deposit in their accounts, up to a maximum of 10 entries per month. In Michigan, the prize is $10,000, in addition to other cash awards.

In Nebraska and Michigan alone, 42,000 individuals have joined "Save to Win," amassing about $72 million in their accounts. But Prize-Linked Savings will only realize its potential for enticing Americans to maintain bank accounts when the government legalizes the sort of multi-million dollar payouts that would draw big media attention. Last October, Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) introduced legislation that would amend various federal laws to make this possible, but the bill got stuck in committee with little chance of passage.

3. Let new approaches to banking flourish.

Businesses are using new technologies to try and lure more Americans into banking. The government needs to stop meddling with these new products.

Prepaid cards, the latest trend in stashing money, have nearly all the virtues of a bank account with few of the drawbacks, and they're bringing order to the finances of millions of Americans. Consumers like prepaid cards because their fees are straightforward and they can't overdraft; banks like them because they're mostly exempt from the Durbin Amendment. In 2012, Walmart and American Express partnered to offer the Bluebird card, and so far users have loaded $2 billion into their accounts, with about a third of those funds coming through direct deposit. Spending through prepaid cards grew by 34 percent a year from 2009 to 2012, making it the fastest growing form of non-cash payment.

Prepaid cardholders need physical locations to deposit cash into their accounts, which is where the U.S. Postal Service sees an opportunity to step in. But given that prepaid customers are trying to save a buck, the last thing they need are storefronts heavily staffed by employees making a median wage of $53,000 plus generous pension benefits. NetSpend, meanwhile, is a prepaid network with 100,000 locations, or more than three times the reach of the USPS. PayNearMe offers its customers 17,000 locations for settling their bills with cash, and unlike post office branches many of these spots (such as the 7-Elevens in PayNearMe's network) are open every day of the week, 24 hours per day.

If lawmakers want to reduce the number of unbanked Americans, they should leave prepaid cards alone. Yet last year, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) introduced a bill (for the second time) that would change the fee structure for prepaid cards and require that providers offer a toll-free number that customers can call with questions. And last month, Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) introduced a bill that would require prepaid cards issuers to be more transparent about fees—a truly pointless piece of legislation since these products already have straightforward fee structures.

Todd Zywicki, a senior scholar at the Mercatus Institute and an expert on banking regulation, says lawmakers haven't moved on either bill because they're waiting to see if the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issues rules for prepaid cards. "A worst case scenario would be if regulators dictate which services prepaid issuers are allowed to charge for," says Zywicki.

When prepaid issuers charge a fee for a customer service call, for example, it helps keep overall costs down. More red tape will only slow the growth of this promising product and push out the small players—just as it has in the traditional banking industry.

The cryptocurrency Bitcoin is another emerging technology that has tremendous potential to drive down the high fees associated with banking services. Foreign-born workers in the U.S. sent $48 billion to their home countries in 2009. For this, they pay an average fee of 6.18 percent. That's because multiple intermediaries are involved in settling these payments, and they all take a cut.

Bitcoin doesn't require an intermediary for a number of reasons. The entire network can see a record of every transaction, which protects users against fraud. And transactions are final so there's no possibility of a charge reversal. Palo Alto-based startup Buttercoin is building a transmission network based on Bitcoin that could replace traditional players like Western Union.

Bitcoin has the potential to eliminate almost all the costs associated with domestic money transfers, which would turn the traditional banking industry upside down to the benefit of consumers. But regulators may stand in the way. Last month, New York held a two-day hearing on how to regulate cryptocurrencies, and the state is expected to introduce a licensing system that could slow innovation in the Bitcoin arena.

The goal for policymakers shouldn't be to bring more low-income Americans into the traditional banking sector, but to allow entrepreneurs to rethink financial services to better fit the needs of low-income Americans. Banks have to earn the business of more American households by using technology to cut costs. A gimmicky idea for occupying a massive federal workforce with a dwindling number of letters to deliver isn't the answer.

On the other hand, the post office does have a lot of branches. How about selling orange juice and gas?

Show Comments (53)