3 Ways to Get More Americans Into Banking (That Don't Involve the U.S. Postal Service)

Policymakers should get out of the way and let entrepreneurs offer financial services that fit the needs of low-income Americans.

When I was a kid, my father went to Chemical Bank every other Friday to deposit his paycheck, which involved walking to a branch, getting in line, and talking to an actual person. My parents kept a stack of twenties in the silverware drawer so they'd have enough cash in between trips to the teller. I remember the smell of the ink on the carbon copy deposit slips, which I would doodle on and sniff while my mother waited in line at our local branch.

Going to the bank—once a ritual of American life—is going the way of twisting rabbit ears into sharp angles to make the TV more watchable. I've never balanced a checkbook. I take cash out (usually en route to the place where I plan to spend it) at one of the ATMs that's on every block in New York City. My paycheck transfers automatically into my account and I deposit checks by snapping photos of them with my iPhone. I got a mortgage last year without ever stepping into a bank. And I'm hardly alone: A 2013 Federal Reserve survey found that a quarter of U.S. adults used mobile banking services in the last year, and that share is expanding rapidly.

By doing away with the need to wait in line and schedule visits around their limited hours, banks have become a lot less like…the post office. So why would it make sense for the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to get involved in the banking business?

The USPS inspector general released a white paper last month arguing that the organization should use its enormous reach—31,272 retail branches—to do just that. Total mail volume has been shrinking on average five percent a year since 2006 and the USPS is drowning in red ink. However, according to the inspector general, the primary goal isn't the survival of the organization but rather helping the "underserved." The report estimates that about 31 percent of U.S. households don't take advantage of traditional banking services, and they spend on average $2,412 yearly on "alternative financial services," like check cashing and payday lending. In The Huffington Post, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) expressed enthusiasm for the idea, promising threatening that "this is an issue I'm going to spend a lot of time working on."

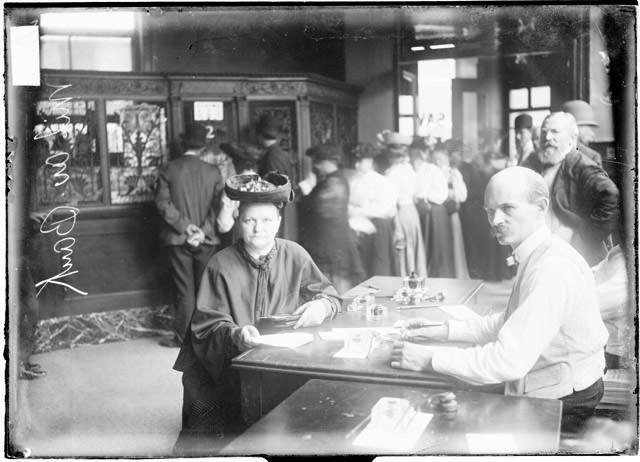

Post office banking is actually an old idea. The USPS offered savings accounts from 1911 to 1967, which paid an anemic interest rate but were popular with cautious savers because they were backed by the U.S. Treasury. But in 1934, the federal government started insuring the balances on all private bank accounts, and as FDIC limits grew Americans dumped their postal savings accounts. By 1965, two years before the system was dissolved, there were just a million depositors with a total balance of $416 million.

If the organization couldn't compete with private banks before the days of mobile banking, why would it be able to grab market share now? Commercial banks are becoming increasingly nimble in an effort to cut costs, making it harder than ever for a federal bureaucracy with an enormous overhead to have a fighting chance.

Vastly reducing the number of unbanked Americans is a worthwhile goal—and one that could be more easily achieved if Sen. Warren and other Washington do-gooders would abandon their backward-looking schemes and get out of the way. Here are three policies that would truly lead more Americans to get into banking:

1. Eliminate price controls by repealing the Durbin Amendment.

According to a 2012 survey by Bankrate.com, only 39 percent of banks offered free checking accounts, down from 76 percent two years earlier. The average monthly cost of maintaining a checking account doubled between 2010 and 2012, to about $5.50 per month. And customers with low balances generally pay steep out-of-network ATM and overdraft fees. Is it any wonder so many U.S. households prefer to keep their money in cash?

The rising cost of banking is an unintended consequence of the government's effort to knock down transaction costs by decree. Banks once collected about 44 cents every time customers swiped their debit cards at the cash register. With debit card use soaring (surpassing credit cards in popularity in 2006), swipe fees became an enormous source of revenue. Banks responded by dropping checking account fees to get their plastic in as many wallets as possible.

An amendment to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, introduced by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), imposed a price cap that reduced debit card swipe fee down to 24 cents. As a result, banks earned $7.3 billion less in revenue from debit cards swipes in 2012 over the prior year. Predictably, banks responded by jacking their checking account fees and refocusing their efforts on signing up wealthy (and more profitable) customers. If the Durbin Amendment were repealed, most banks would likely go back to offering free checking accounts and otherwise courting the business of low-income Americans.

2. "Savings with a Thrill:" Let banks run lotteries.

When I opened my first savings account in 1990, the interest rate was about 5 percent, meaning I could earn $50 a year on a balance of $1,000. Today, the average money market account pays an annual return of 0.41 percent, yielding just $4.10 per year on that $1,000 balance. But what if banks took that trickle of money and entered it in a lottery to give account holders a small chance at earning some real dough?

Prize-Linked Savings (PLS), the industry term for attaching a lottery to a bank account, is a proven way to encourage saving. A 2010 National Bureau of Economic Research paper traced this idea back to seventh-century England. More recently, PLS accounts have been offered in Latin America, Spain, Germany, Indonesia, and Japan. After World War II, the U.K. introduced saving bonds with award incentives, advertising them as "Savings with a Thrill!"

It's no wonder so many folks are enticed by even the remote possibility of a big payday. Melissa Kearney, a University of Maryland economist and an expert on PLS, told PBS' Newshour: "It's often thought that people are irrational when they play the lottery, but I would challenge that assumption. If you're a low-income individual, how else can you potentially win enough to buy a house or really change your life?"

PLS is prohibited in the U.S. by several federal and state laws that enforce the government's monopoly on running lotteries. But thanks to legislative carve-outs, credit unions in Washington state, North Carolina, Michigan, and Nebraska have adopted a PLS program called "Save To Win." In Washington, savers get a shot at winning a $5,000 prize and multiple other cash awards for every $25 they deposit in their accounts, up to a maximum of 10 entries per month. In Michigan, the prize is $10,000, in addition to other cash awards.

In Nebraska and Michigan alone, 42,000 individuals have joined "Save to Win," amassing about $72 million in their accounts. But Prize-Linked Savings will only realize its potential for enticing Americans to maintain bank accounts when the government legalizes the sort of multi-million dollar payouts that would draw big media attention. Last October, Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.) and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) introduced legislation that would amend various federal laws to make this possible, but the bill got stuck in committee with little chance of passage.

3. Let new approaches to banking flourish.

Businesses are using new technologies to try and lure more Americans into banking. The government needs to stop meddling with these new products.

Prepaid cards, the latest trend in stashing money, have nearly all the virtues of a bank account with few of the drawbacks, and they're bringing order to the finances of millions of Americans. Consumers like prepaid cards because their fees are straightforward and they can't overdraft; banks like them because they're mostly exempt from the Durbin Amendment. In 2012, Walmart and American Express partnered to offer the Bluebird card, and so far users have loaded $2 billion into their accounts, with about a third of those funds coming through direct deposit. Spending through prepaid cards grew by 34 percent a year from 2009 to 2012, making it the fastest growing form of non-cash payment.

Prepaid cardholders need physical locations to deposit cash into their accounts, which is where the U.S. Postal Service sees an opportunity to step in. But given that prepaid customers are trying to save a buck, the last thing they need are storefronts heavily staffed by employees making a median wage of $53,000 plus generous pension benefits. NetSpend, meanwhile, is a prepaid network with 100,000 locations, or more than three times the reach of the USPS. PayNearMe offers its customers 17,000 locations for settling their bills with cash, and unlike post office branches many of these spots (such as the 7-Elevens in PayNearMe's network) are open every day of the week, 24 hours per day.

If lawmakers want to reduce the number of unbanked Americans, they should leave prepaid cards alone. Yet last year, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) introduced a bill (for the second time) that would change the fee structure for prepaid cards and require that providers offer a toll-free number that customers can call with questions. And last month, Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) introduced a bill that would require prepaid cards issuers to be more transparent about fees—a truly pointless piece of legislation since these products already have straightforward fee structures.

Todd Zywicki, a senior scholar at the Mercatus Institute and an expert on banking regulation, says lawmakers haven't moved on either bill because they're waiting to see if the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issues rules for prepaid cards. "A worst case scenario would be if regulators dictate which services prepaid issuers are allowed to charge for," says Zywicki.

When prepaid issuers charge a fee for a customer service call, for example, it helps keep overall costs down. More red tape will only slow the growth of this promising product and push out the small players—just as it has in the traditional banking industry.

The cryptocurrency Bitcoin is another emerging technology that has tremendous potential to drive down the high fees associated with banking services. Foreign-born workers in the U.S. sent $48 billion to their home countries in 2009. For this, they pay an average fee of 6.18 percent. That's because multiple intermediaries are involved in settling these payments, and they all take a cut.

Bitcoin doesn't require an intermediary for a number of reasons. The entire network can see a record of every transaction, which protects users against fraud. And transactions are final so there's no possibility of a charge reversal. Palo Alto-based startup Buttercoin is building a transmission network based on Bitcoin that could replace traditional players like Western Union.

Bitcoin has the potential to eliminate almost all the costs associated with domestic money transfers, which would turn the traditional banking industry upside down to the benefit of consumers. But regulators may stand in the way. Last month, New York held a two-day hearing on how to regulate cryptocurrencies, and the state is expected to introduce a licensing system that could slow innovation in the Bitcoin arena.

The goal for policymakers shouldn't be to bring more low-income Americans into the traditional banking sector, but to allow entrepreneurs to rethink financial services to better fit the needs of low-income Americans. Banks have to earn the business of more American households by using technology to cut costs. A gimmicky idea for occupying a massive federal workforce with a dwindling number of letters to deliver isn't the answer.

On the other hand, the post office does have a lot of branches. How about selling orange juice and gas?

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

A solution in search of a problem.

While reducing the number of unbanked Americans is a worthwhile goal,

Why? Is there any reason to believe that a nontrivial number of the "unbanked" are that way even though they don't want to be?

Beat me to it. Some people don't want to screw with a bank. Who is Reason or anyone else to say they shouldn't be able to make that choice?

Even with the bullshit Dodd Frank law that ended free checking, banking is not so expensive that people who want to don't because they can't afford it.

The reality is that with prepaid debit cards and check cashing services, banking is less necessary for some than it used to be.

There are actually a number of reasons people avoid banks. Legitimate ones, I mean. Some just don't trust banks, some have low enough funds to want to avoid fees, some find consumer finance companies, payday lenders, etc. more convenient to deal with.

Perhaps less legitimately, though understandable in many instances, are people who are working off the books and don't want the bank to go reporting their income to the government.

Or places like that evil Walmart who charge a flat $3 for check cashing.

Having worked in the banking business for thirty years now I can pretty much assure everyone that anyone who wants a bank account can have one. CRA already demands that banks service "under serviced" communities and there are so many alternatives to the traditional brick and mortar banks that everyone already has access to services if they wish. Non-traditional banking is far more convenient, and cheaper, than traditional banking not to mention that non-traditional banking for the most part avoids privacy killing FinCen requirements. Honestly, I'm glad that I'm closer to the end of my career than the beginning.

For sure. The other thing about getting a bank account is they require a stable address. Some people don't have that and I don't mean homeless people. If you are staying on your friend's couch working a job for the summer, your friend may not want your mail going to his address or if you are renting say a bedroom from someone who is renting themselves and thus not supposed to sublet, you can't get your mail sent there without someone noticing. And PO Boxes are expensive as hell to rent.

"Free checking with every P.O. Box. Only at USPS!"

Don't trust banks? Why not? I mean, the government controls them, so they must be safe! They insure them, they tell them who they have to make home loans to, tell them how they have to make subprime loans to people with bad credit... what's the worst that could happen?

Who is Reason or anyone else to say they shouldn't be able to make that choice?

Is someone saying that people ought to be forced to use a bank?

Yeah, it's called "ideology". *rimshot*

Expect to hear the phrase "banking desert" come around soon.

I recently started using prepaid debit cards again because I've had it with my "proper" bank.

I could see that. You can pay most bills now over the phone using a debit card. Unless you work for an employer who insists on direct deposit, you don't need a bank.

Actually, most of the prepaid cards these days encourage direct deposit, and even offer to waive the monthly fee for doing so.

Naturally, I don't want to volunteer too much about my particular situation of late, but I've been in a place where even those nickel and dime fees look really cheap compared to how my "real" bank's been treating me, and my more urgent bills need to come first. I've also found a couple of ways to get around transaction fees and such with the prepaid cards.

I didn't know you could direct deposit on a prepaid card. Interesting. No wonder the feds hate those cards so much. They basically render all of the prohibitions against cash smuggling and the requirements for banks to inform the IRS of deposits over $10,000 moot. I guess that explains why the only people you ever hear about getting tagged by the IRS or DOJ for depositing too much cash are law abiding and unlucky people. I am sure criminals don't bother with banks to launder their money anymore.

Actually a lot of drug cartels are going so far as to convert money into in-game currency on World of Warcraft and then transfer it to another "player" in another country. Prepaid cards are slower than what's going on now.

I use this stuff called *cash*.

My pay goes directly to my credit union account... which does not have a convenient branch near me. So I opened a TD account with 1K and once a week cash a credit union check at TD.

It helps me manage my spending, as I can always see when I'm running low.

And if I have extra cash, it's nice to stash it away for those times I need a little more. At least that's the theory. I'll let you know how that works if it ever happens.

Oh wow man that makes a lot of sense dude.

http://www.Anon-VPN.com

The USPS is part of the government, so there won't be a problem with funneling bank records directly to the FBI, DEA, et c.

Think of the time we'll save.

My second thought. The first being I can't imagine an organization I would trust less with my money. I'd sooner give it to the mob.

Guess what, your bank already does that under the know your customer laws.

"underserved."

A euphemism for "not under our control."

^THIS^

Vastly reducing the number of unbanked Americans is a worthwhile goal

[citation needed]

As with too many other industries, the government interfering in banking and lending has screwed consumers much more than it's helped them. Just the bailout alone prevented a massive move from the failed institutions to medium-sized and not-as-stupid large banks. I also suspect that all of those houses sitting out there years after the crash would've hit the markets long ago in banks and lenders were forced to cut their losses or dump assets in bankruptcy.

I was at Kmart not long ago, and above the service desk is a big sign offering check cashing, bill payment, and money transfer services.

I suspect a lot of people find a COD service with known costs to be much cheaper in the long run than a bank.

Yes, Walmart does the same for payroll checks, $3 fee for up to $1000 and $6 for up to $5000 I believe. Pretty damn cheap.

I don't know about Walmart, but some stores will refund the check fee if you spend some money at the store.

Who in their right mind would deposit money with a company that is losing billions of every year, and happens to be part of the government so its effectively immune to efforts to get your money back? Is there really any question that they'd shortly starting using deposits to plug their pension shortfall?

At first I liked the idea of putting predatory lenders out of business, but it didn't take long to realize that already long waits at the post office, as a consequence of consolidation, would only get worse if the USPS becomes an alternative bank. Not unlike how lottery sales in Georgia have made "convenience" stores much less so.

I've never understood why people find this narrative so appealing. It doesn't make logical sense. The story goes that there are financial institutions who thrive off giving bad loans to people who can't pay them back and whose collateral assets are not even enough to recoup losses. Banks wouldn't be giving out loans to lose money and they don't. The cost of these loans is subsidized by the government who inevitably step in to buy up the bad debt. "Predatory lending" is something that exists by virtue of public policy perverse incentives, not free market incentives.

Poor loan decisions? If the government offered to pay you for every unprofitable you gave out, thereby making those loans profitable, how is that a poor decision on your part? The poor decisions are being made by policy makers who underwrite losses.

I was specifically thinking of payday lenders, car title lenders, and the like, the regulation of which varies by state. It's not *as* bad in Georgia as it used to be, but if you resort to pawning your car title, you can really get worked over.

If you lose your crappy cars to a payday lender enough times, you'll probably wise up and manage your finances a little better. It's a good market force.

Who is losing billions every year?

The big banks are enormously profitable after massive writedowns and losses for poor loan decisions in 2009-10.

Even Fannie Mae spit out $80 billion in profit last year.

Who is losing billions every year?

The taxpayers subsidizing their losses.

The postal service is losing billions per year.

Yes - good point.

By the miracle of changing the general accounting practices for banks, banks are now enormously profitable.

It also helped that they were able to exchange their crappy illiquid mortgages for cash and Treasuries from the Fed and US Govt.

much like Obamacare, Liz Warren, the CFPB and Dodd Frank claimed their layers of regulation and compliance would save consumers an average of $700 on closing costs for a mortgage. studies show it added an average of $700 in closing costs.

Mostly, that picture makes me rue the day I did NOT buy several USPS Jeeps when they took them out of service.

1) really cool

2) well maintained

3) lots of fun

4) hard top!

5) worth money now

Shit. Just have to make do with the old TJ for now...

Also, fuck the USPS, especially re: banking. NO.

But they had the steering wheel on the wrong side. You would have to move it back to the left or move to Britain.

Moving to the left and moving to Britain ..... kind of the same thing, no ?

They simultaneously try to drive retail banking out of business and try to enroll more people in traditional retail banks. "What we need is more regulation to counteract the negative effects of regulation."

It won't stop until we live in a fascist paradise.

The USPS has consistently proven to be a money pit. Now they want to handle my money? No thanks. You don't have to be a genius to make that connection.

After Dodd-Frank my bank tried to raise fees on checking and atm transfers, but I just switched to a credit union. No fees for anything plus it's through my university so it helps them.

Mail guy was still driving one of those old beat up Willy's a few years ago.

There is no reason for any renter to let a bank invest their savings. Mortgage loanable funds only drive up housing. Banks' balance sheet mismatch creates financial crises/bubbles - and the working poor are the ones who pay the highest price for that.

Banks are not free market. Government-granted monopoly over legal tender, wholesale settlement/exchange, FDIC guarantees, a primary dealer cartel. Government is never going to allow true free market competition in money a la Hayek. But it is in the interest of both the government and citizenry to, at least, break up the monopoly a bit.

Having a postal savings/settlement system - invested solely in short-term Treasuries - is an excellent idea. Not because of 'unbanked poor people' - but because of its effect on those separate government-granted monopolies.

Busting a monopoly is not the same thing as allowing for a free market, but the mere existence of TWO government-debt money systems will at least awaken economists to the notion that 'money' itself is laden with unexamined assumptions inside 'macroeconomics'. Those assumptions about money itself generally lead to making excuses for government-granted monopoly and cronyism. eg - the nonsense in this article that 'banks' are somehow 'free market' and pure while the 'post office' is 'government'.

Proving that, yes, even experts in economics can be irrational. Or, don't know what rational means.

An outcome you would prefer existing in the event space with a positive probability != rational.

"If you're a low-income individual, how else can you potentially win enough to buy a house or really change your life?"

Because _only_ through winning a lottery can someone figure out a way to buy a house or really change their life. Stupid is as stupid does.

Elizabeth Warren's policy instincts are invariably inversely correlated with what is best for those who she purports to be an advocate. The poor are the most affected by inevitable economic decline that accompanies big government and 'social welfare' programs

Proposed:

Amendment 28 to the US Constitution:

Unless they can convince 2/3 of the population in 2/3 of the states that there's a valid reason for them to intervene in an issue, Congress has the right to shut it's pie hole and mind it's own business.

The people can vote on issues every other year.