On May 29, 2020, the Supreme Court denied an injunction in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom. The Court's order was a single sentence. Chief Justice Roberts wrote a solo concurrence that stretched about two pages. According to Westlaw, 114 cases have cited the Chief's concurrence. (I cited many of these cases in my Harvard JLPPP article). And only one of those case has negatively referenced the opinion. In six months, South Bay may have become Chief Justice Roberts's most influential precedent during his entire tenure on the Court.

To be sure, Roberts has written many important decisions. But those cases affected discrete controversies. NFIB v. Sebelius resolved the constitutionality of the ACA. Shelby County v. Holder resolved the status of the Voting Rights Act. The Census and DACA cases resolved controversies specific to the Trump era. And so on.

But his South Bay concurrence settled cases of first impressions that have spanned across the entire spectrum of constitutional adjudication. Courts have cited South Bay in cases involving every facet of the Bill of Rights: the Freedom of Speech, the Free Exercise of Religion, Freedom of Association, the Second Amendment, various criminal procedure rights (such as the right to a speedy trial), and the Eighth Amendment (conditions for prisoners). South Bay has been cited in substantive due process cases, involving rights to contract and rights to abortion. South Bay has been decisive in cases involving voting rights during the pandemic. Courts have relied on South Bay to determine the police powers of governors to impose mask mandates and other quarantine measures. In disputes between state and localities, South Bay has served as a tiebreaker.

It is difficult to account for how broadly governments at all levels have relied on the Chief's opinion. Conservatives and liberals have latched onto the Chief's cursory analysis as the end-all be-all of COVID-deference. Before South Bay, several courts actually ruled for the religious claimants. But since South Bay, houses of worship have consistently lost. Truly, the impact of the South Bay concurrence has been staggering.

Regrettably, courts have failed to account for the narrow context in which South Bay arose. The Plaintiffs sought an injunction pending appeal. The crux of Roberts's concurrence is that the Supreme Court should not grant an injunction pending appeal unless the "'the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear' and, even then, 'sparingly and only in the most critical and exigent circumstances.'" This standard is well known, and does not in any way depend on the COVID-19 pandemic. The Chief cited Jacobson, briefly, but only noted that the government should get deference during the "dynamic" pandemic.

In the abstract, it isn't clear that South Bay should serve as a precedent, at all, for district court and courts of appeals. Plaintiffs do not need to show their claim for relief is "indisputably clear" to obtain preliminary injunctive relief. Yet, courts have reflexively cited the Chief's opinion, as if it were a super precedent that governs all things COVID. It is not. It is a solo concurrence from the shadow docket. Judge O'Scannlain accurately described the status of South Bay in his Harvest Rock dissent.

I first clarify a point that is somewhat obscured by the majority's decision: we are neither bound nor meaningfully guided by the Supreme Court's decision to deny a writ of injunction against California's restrictions on religious worship services earlier this year. See South Bay United Pentecostal Church, 140 S. Ct. at 1613. That decision, which considered a challenge to an earlier and much different iteration of California's restrictions, was unaccompanied by any opinion of the Court and thus is precedential only as to "the precise issues presented and necessarily decided." Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 176 (U.S. 1977) (per curiam). In that case, the Supreme Court considered whether to issue a writ of injunction under the All Writs Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a), a more demanding standard than that which applies to the motion for an injunction pending appeal here. . . . . Without any opinion of the Court, we have no guidance whatsoever—not even in the form of "dicta" as the majority suggests, Maj .at 7—as to why the Court declined to provide such an extraordinary remedy, and we certainly have no basis to infer that a majority of theCourt agreed upon some unstated rationale that somehow applies equally here.

The Supreme Court should not set binding precedent from concurrences in an unargued case. Chief Justice Roberts wrote for a very specific context, yet more than a hundred of judges have cited it in unrelated circumstances. Truly, the South Bay concurrence has taken on a life of its own, far beyond the Chief's intentions.

Fortunately, a pending case affords the Court an opportunity to clarify the appropriate standard for First Amendment cases, in the proper posture. Agudath Israel of America v. Cuomo presents a challenge to New York's restrictions on Houses of Worship (I serve as co-counsel with the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty on a related case on behalf of a Jewish school in New York). Agudath Israel sought an injunction from the Supreme Court, and in the alternative, requested a petition for certiorari before judgment. (There is a related pending case, The Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, that did not request cert before judgment.)

A cert grant now would clarify the relevant standard, and settle a pre- and post-South Bay circuit split. The brief explains:

Certiorari is further warranted given the conflicts between the Second Circuit's decision and decisions of other Circuits and of this Court. The Second Circuit declined to apply heightened scrutiny even though the Cluster Initiative treated houses of worship worse than so-called "essential" businesses, App. 6 (Park, J., dissenting), simply because (in some zones) the Cluster Initiative also imposed stringent restrictions on other entities, like schools and restaurants, App. 4 (majority). Yet the Sixth Circuit subjected a Kentucky COVID-19 order to heightened scrutiny because it closed houses of worship but not other "life-sustaining" organizations, without regard to which other entities were closed, too. Roberts v. Neace, 958 F.3d 409, 411–15 (6th Cir. 2020) (per curiam). And the Third Circuit has held that even a single secular exemption to an otherwise-applicable prohibition can render a law not neutral and generally applicable as applied to religion, regardless whether other secular conduct is likewise banned. Fraternal Order of Police v. City of Newark, 170 F.3d 359, 365–66 (3d Cir. 1999); see Calvary Chapel, 140 S. Ct. at 2613 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) ("The point is not whether one or a few secular analogs are regulated. The question is whether a single secular analog is not regulated." (citation omitted) (emphasis in original)).

Enough emanations and penumbras from the shadow docket. The Court should grant certiorari, and settle these landmark issues in the proper postures. Arguments could be set for December 9, the last day of the current November sitting, and decided in January. (The Court could follow a similar expedited calendar for the census case). Let's settle this issue the right way.

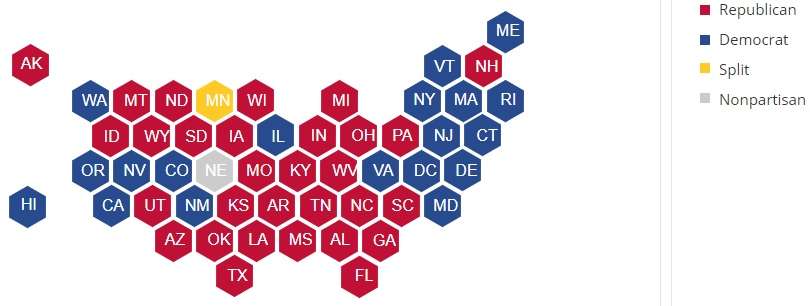

Here, the dynamics may be difficult for the Chief. Justice Kavanaugh, and the three other Calvary Chapel dissenters can push to grant cert before judgment. Justice Barrett may even grant a courtesy fifth. At that point, the Court would hear the case. The South Bay test, which was limited to injunctive relief, would no longer be binding. At that point, I suspect there would be five votes to limit New York's expansive restrictions on the Free Exercise of Religion. The Chief could then choose to be in dissent. Or, more likely, he would find a way to stay in the majority. Perhaps by issuing a more narrow decision that permits the Houses of Worship to open with certain social distancing measures--measures they were already complying with.

This dance will become familiar to Roberts. I cannot think of any Chief Justice in history who was consistently in dissent. And Roberts would not want to be the first. So he will have to find ways to moderate to the right, without losing the conservative flank. Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett now become kingmakers. They can seek the Chief's joinder, or forge their own path. Now it is Roberts's choice.

See

See

Show Comments (14)