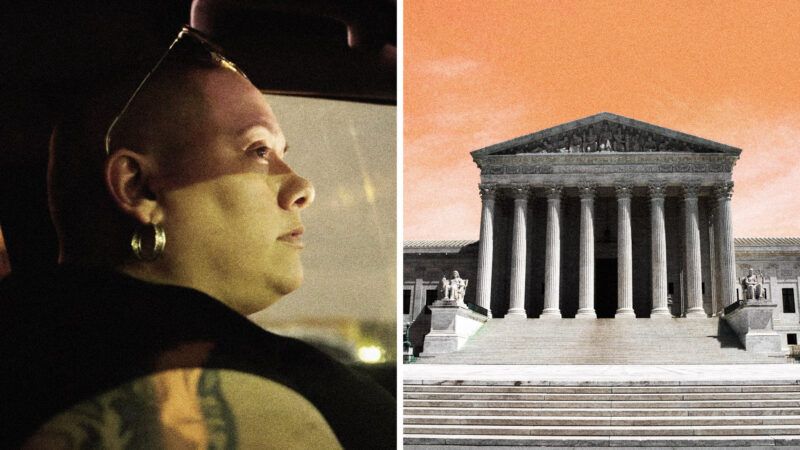

This Reporter Was Arrested for Asking Questions. The Supreme Court Just Revived Her Lawsuit.

Priscilla Villarreal's case is about whether certain reporters have more robust free speech rights than others.

The Supreme Court on Tuesday threw out a ruling against a Texas citizen journalist whom police arrested for asking the government questions, injecting new life into a free speech case that essentially asked if reporters working outside traditional media are entitled to a weaker version of the First Amendment.

Journalist Priscilla Villarreal's lawsuit will now go back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. The judges there ruled 9–7 earlier this year that it was not clearly unconstitutional when law enforcement in Laredo, Texas, leveraged an obscure Texas statute to try to punish her for her reporting.

Known in Laredo as "Lagordiloca"—which translates roughly to "the fat, crazy lady"—Villarreal has built a large Facebook following over the years by livestreaming directly from crime scenes and traffic accidents. She is a celebrity around town, known for her colorful and profane commentary, as well as for her muckraking, which has zeroed in at times on law enforcement misconduct.

That's why, she says, the police devised a way to retaliate against her. "They were just looking for something to arrest me," Villarreal told me in Laredo last November. "Because I was exposing the corruption, I was exposing them being cruel to detainees….They were doing things they weren't supposed to."

In 2017, law enforcement zeroed in on her after she published a story about a family involved in a fatal traffic accident and another about a Border Patrol agent who'd committed suicide. Villarreal corroborated her information with a source within the Laredo Police Department, which then arrested her for doing so.

To set that in motion, the government invoked a statute that criminalizes soliciting nonpublic information if the person asking intended to "benefit" from it. Law enforcement said Villarreal personally gained from her reporting by getting attention on Facebook. Though it appears to have been written to discourage government corruption, the police used the law to make a crime out of standard journalism: seeking information not yet known and publishing it.

Despite looking to many ideologically diverse organizations—from Christian conservatives to libertarians to progressives—like a textbook violation of the First Amendment, Villarreal had mixed results in court. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas gave the public employees qualified immunity, which blocks federal civil suits against state and local government actors if the way in which they allegedly violated the Constitution had not yet been "clearly established" in prior case law. That opinion was then forcefully overturned by the 5th Circuit. "If that is not an obvious violation of the Constitution," wrote Judge James C. Ho, "it's hard to imagine what would be."

But that conclusion ruffled some feathers on the same court, which voted to have the full spread of judges—as opposed to the typical three-person panel—re-hear the case. In January, a sharply divided 5th Circuit reversed that decision. "Villarreal and others portray her as a martyr for the sake of journalism. That is inappropriate," wrote Judge Edith Jones for the majority. "Mainstream, legitimate media outlets routinely withhold the identity of accident victims or those who committed suicide until public officials or family members release that information publicly." The defendants were again given qualified immunity.

The Supreme Court's ruling today throws out that decision and adds yet another reversal to Villarreal's collection. The justices ordered the 5th Circuit to reconsider in light of the high court's recent guidance in Gonzalez v. Trevino, in which the majority last summer made it easier for victims of retaliatory arrests to get their day in court. Gonzalez, too, centered on a woman who was allegedly targeted and arrested for her speech, and the Court's ruling there also overturned a decision from the 5th Circuit.

Show Comments (80)