How the Feds Destroyed Backpage.com and Its Founders

By prosecuting the website's founders, the government chilled free speech online and ruined lives.

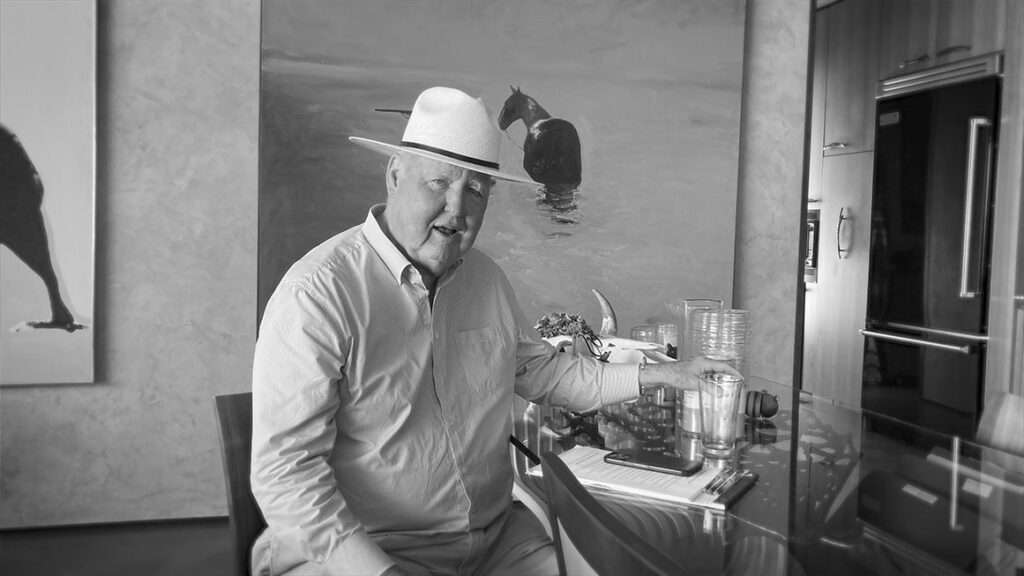

HD Download"I'm having the lawyers inquire as to whether or not I can bring a library with me to prison," Michael Lacey said with resignation. The Backpage co-founder and former alt-weekly magnate was standing in the library of his labyrinthine Paradise Valley, Arizona, home. The room abuts one of Lacey's two home offices, each teeming with books, family photos, journalism awards, and file folders—a mix of case files and past work he's been combing through as he works on a book proposal.

It was March 2024, and Lacey was still holding out hope of avoiding federal prison. But prosecutors were eager to send him there, and Lacey recognized that may well be his fate.

I was there with a Reason video crew, interviewing Lacey for a documentary. This was my second visit to Lacey's home. The first, in 2018, was not long after the feds raided the place, and the vibe was different then. Lacey and his longtime friend and business partner James Larkin were pissed but not dejected. They cracked jokes about their enemies—folks such as Sen. John McCain (R–Ariz.) and former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio. They told elaborate stories about the heyday of their alt-weekly empire, finishing each other's sentences. They broke out wine from Larkin's vineyard and vowed they would fight this to the end.

Larkin committed suicide a week before the pair's second federal trial was scheduled to start in August 2023.

In my second visit, Lacey was still cracking jokes and telling stories. But no one was there to finish his sentences, to remind him of the name of some official they angered once upon a time, to laugh with him about the wild office parties they threw in the 1970s, to try to rein him in (not always successfully) when his language got a little too colorful. "I still catch myself before I've had coffee, saying 'Ah, I've got to send this to Jim,' OK? I'll see something and it's like: 'Oh, fuck. No sending anything to Jim.'"

In September, Lacey turned himself over to the U.S. Marshals—no library in tow, unsure even where he'd be imprisoned. Prosecutors recommended a 20-year sentence for the 76-year-old Lacey. U.S. District Judge Diane Humetewa instead sentenced him to five years plus a $3 million fine.

Lacey's path from journalist to felon is at once unique—a product of particular times, temperaments, technological changes, and moral panics—and all too familiar. It's a story of how far government agents will go to punish people who defy them, and a playbook for authorities intent on wresting more control over online speech of all sorts.

How It Started

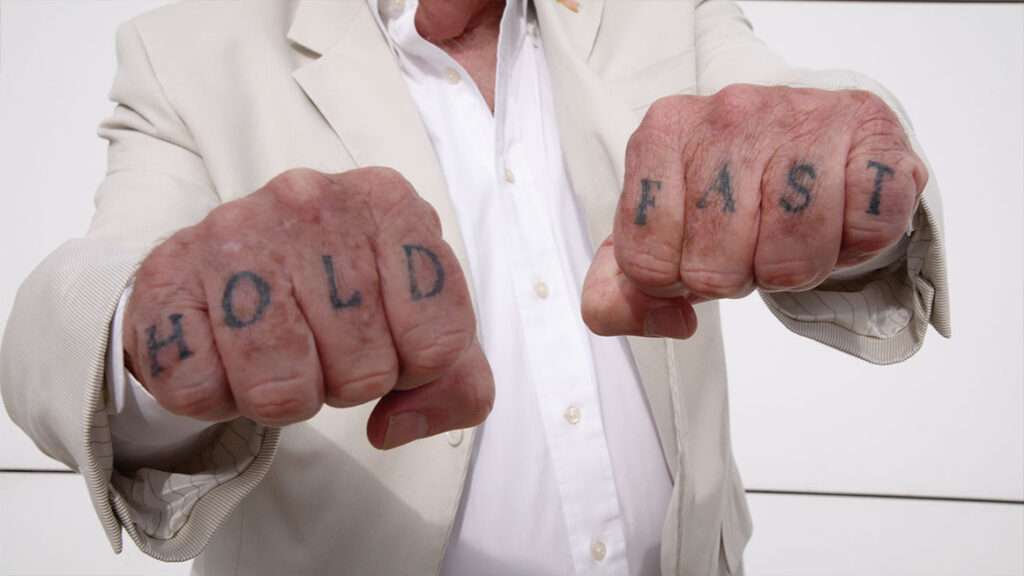

Lacey and Larkin were no strangers to First Amendment conflicts when the Backpage prosecution started. Their friendship and business partnership began as part of the team running a scrappy anti-war student paper called the Arizona Times that launched in 1970. It would grow into the Phoenix New Times, a thriving weekly unafraid to skewer Arizona power players, including Arpaio, McCain and wife Cindy, and many others.

In the 1980s and 1990s, their portfolio grew to include alternative weeklies in more than a dozen cities, including the iconic Village Voice in Greenwich Village. Lacey mainly handled editorial and Larkin handled the business end of things.

Both fought in court again and again, defending their First Amendment right to distribute, write, and—this is the part that finally brought them to ruin—run ads as they saw fit. New Times was even convicted in 1971for running an abortion services ad, but it fought the case to Arizona's Court of Appeals, which ruled in the paper's favor and struck down the state's law against advertising abortions or birth control.

In 2004, Lacey and Larkin launched the website Backpage as an extension of the classified ads that had always run in the back of their newspapers (and most other newspapers). Backpage.com had all the sections you would find in its print counterparts, including apartments for rent, job openings, and personals and adult services ads, separated by city.

At first, nobody paid much attention to the site. When attorneys general declared war on adult services ads online in the late 2000s, the similar but better-known Craigslist was the platform in their crosshairs.

Though newspapers had for decades published ads for escorts, phone sex lines, and other forms of legal sex work, Craigslist's online facilitation of these ads coincided with two burgeoning moral panics. The first concerned the rise of user-generated content—platforms such as Craigslist and early social media entities that allowed speech to be published without traditional gatekeepers.

The second panic: sex trafficking. A coalition of Christian activists and radical feminists had been teaming up to push the idea that levels of forced and underage prostitution were suddenly reaching epidemic proportions. To support this narrative, they tended to conflate all prostitution or even any sort of sex work with coerced sex trafficking.

Becoming a Target

"Sex trafficking is usually the way it was framed, even when it was consensual sex work," says Techdirt founder and editor Mike Masnick, who has been covering tech policy since the 1990s. "Finally Craigslist was like, 'forget it.'" The platform shuttered its adult ad section. "And then you have the same A.G.s complaining about Backpage. And it's like, 'Oh, OK, that's where everybody went.'"

In 2012, then–California Attorney General Kamala Harris said: "Backpage.com needs to shut itself down when it has created as its business model the profiting off the selling of human beings and the purchase of human beings….Good businesses, such as Craigslist, understood how it could be abused and mishandled and they shut that aspect of their business model down."

Harris was far from alone in making these kinds of statements. For years, politicians right and left had pushed the narrative that Backpage actively allowed ads for human trafficking, including the trafficking of underage girls.

It wasn't true. The company prohibited ads for illegal conduct; it reported posts by people suspected of being underage to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children; and it worked with law enforcement agencies, including local cops and the federal Department of Justice, to bring down people who used the site to perpetuate sexual exploitation and abuse.

"Based on the reporting and the details and everything that's come out in the court documents, it appeared that they took the role of doing content moderation seriously," Masnick says.

Prosecutors would later argue many of the ads were only thinly veiled enticements for prostitution. Backpage would argue that so long as ads involve seeming adults who weren't explicitly offering prostitution, the posts were legal and so was providing a forum for them.

"You can't tell from looking at an ad on a site like that whether or not it is for, in fact, an escort service—which is legal in most states, I think licensed in a majority of states—or someone who posts the ads but intends to engage [in prostitution], which is illegal in most jurisdictions," says First Amendment lawyer Robert Corn-Revere, who now works as chief counsel for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. "Nor can you tell from the face of those ads that it would have anything to do with [sex] trafficking."

Backpage was a business "that not just one but every single lawyer that looked at the business said, 'This is legal,'" says Lacey. "And because we made enemies politically, all that got overlooked."

Backpage "ended up with relationships with police departments" across the country, he adds. The person overseeing this collaboration—sometimes even testifying in court against alleged traffickers on behalf of prosecutors—was Backpage CEO Carl Ferrer, who got a certificate from then–FBI Director Robert Mueller thanking him for his cooperation.

Federal prosecutors acknowledged Backpage's helpfulness in confidential memos from 2012 and 2013 that I obtained in my reporting. "Backpage is remarkably responsive to law enforcement requests," prosecutors wrote in such a memo. The staff "often takes proactive steps to assist in investigations." Backpage "genuinely wanted to get child prostitution off its site." Witnesses "consistently testified" that Backpage "was making substantial efforts to prevent criminal conduct [and] was conducting its businesses in accordance with legal advice."

A judge wouldn't allow those exculpatory memos to be admitted in court after prosecutors accidentally turned them over to the defense team. "Not only not admissible but ordered physically destroyed," says Lacey. "I've never heard of that."

"What changed between [when the memos were written] and when the prosecution happened in 2018 is that Backpage had been increasingly successful in its First Amendment litigation, and the political pressure to do something, anything, to make Backpage go away increased during that time," says Corn-Revere, who was at one point part of a firm that represented Lacey and Larkin in court. "These [were] guys who did not back down from a fight. And so when the political pressure to do something about Backpage increased, their impulse was to fight back."

The Real Target?

Even as prosecutors privately concluded that Backpage was trying to be law-abiding and helpful, the idea that Backpage was an open purveyor of child sex trafficking persisted in public. Lacey and Larkin were convinced this stemmed from a personal vendetta by politicians their papers had criticized through the decades.

It's true old enemies such as the McCains were among those leading the crusade against Backpage. It's also not hard to believe Lacey and Larkin's longrunning battles with political powerhouses—along with the media enemies they had made in buying up flailing alt-weeklies around the country—contributed to an atmosphere where prominent defenders were few and far between.

But in many ways, their problems arose from being the right tech platform at the wrong time. Sex trafficking panic had reached epic proportions, and hardly anyone—including the journalists and civil liberties groups who might normally defend free speech—seemed willing to defend the First Amendment rights of sex workers or online publishers associated with them for fear of appearing soft on sex trafficking.

Accordingly, this panic proved handy for politicians who wanted to more broadly undermine free speech protections online.

"We're the canary in the coal mine for the internet," Larkin told Reason in 2023.

Backpage was sued by alleged victims of trafficking—a number of whose perpetrators had been punished after the site cooperated with law enforcement—but judges kept dismissing these cases. A Chicago-area sheriff bullied credit cards into ceasing business with Backpage; a federal court ruled that unconstitutional. Then–Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley, now a Republican senator, sought criminal and civil sanctions against the company. And Harris teamed up with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton in 2016 to file pimping charges against Backpage.

"Raking in millions of dollars from the trafficking and exploitation of vulnerable victims is outrageous, despicable and illegal," said Attorney General Harris at the time. "Backpage and its executives purposefully and unlawfully designed Backpage to be the world's top online brothel."

Harris, who was running for the U.S. Senate at the time, received much national attention for taking down alleged sex traffickers.

A California judge threw out the Harris pimping charges—twice. "Providing a forum for online publishing is a recognized legal purpose that is generally provided immunity under" the Communications Decency Act (CDA), wrote Judge Lawrence G. Brown of the Sacramento County Superior Court in his August 2017 decision. (This did not stop the Harris presidential campaign from having a speaker at the Democratic National Convention favorably mention the criminal charges.)

Under Section 230 of the CDA, interactive computer services (and their users) cannot be subject to state criminal charges, or any sort of civil lawsuits, for content created by third parties. If someone posts an actionable threat on Facebook, Facebook is not liable. If you reshare a video that contains slander, the creator of that video is liable, not you. If the world's dumbest murderers use Gmail to hatch a murder plot, Google won't be liable for murder. And if an online ad for escort services leads to folks meeting up and engaging in criminal activity, the parties engaged in that activity are liable, not whatever forum facilitated their introduction.

Some politicians, lawyers, and activists seem to hate Section 230 because it limits punishment—as well as financial damages and asset forfeiture—to the often not-very-wealthy parties committing crimes instead of the deep-pocketed tech intermediaries where communications related to the crime appeared. For more than a decade, they've been seeking to undermine Section 230 protections, with state attorneys general pressuring Congress to change or obliterate the law. Members of Congress often accuse major tech platforms of horrific crimes (including facilitating sex trafficking, terrorism, drug trafficking, mass shootings, sexual exploitation of minors, and more) because the actual perpetrators of these crimes used said platforms.

"There's this weird belief that the best way to deal with bad speech is just to make the company stop it from happening at all," says Masnick. "Like silencing speech somehow makes the underlying problems go away. And that's rarely true, if ever."

The only congressional weakening of Section 230 to be successful so far stemmed from allegations that platforms such as Backpage were enabling sex trafficking. In 2018, Congress passed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) under the pretense that it was needed to hold websites such as Backpage "accountable"—a claim called into question by the fact that Backpage had been shut down and federal charges filed just before former President Donald Trump signed FOSTA into law.

Blood on the Government's Hands

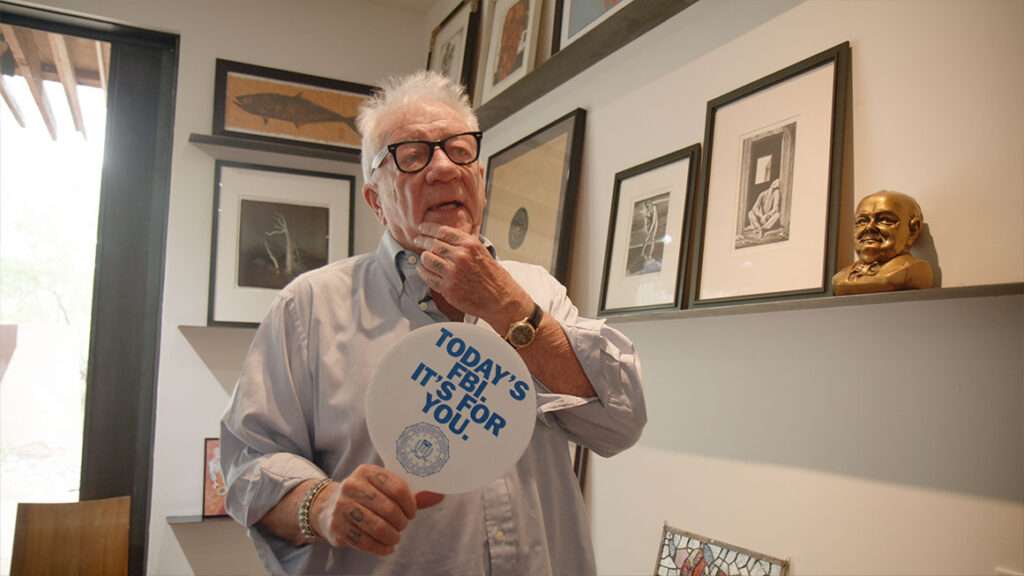

One day in 2018, Lacey was sitting at his desk in his home office when he saw something out of the corner of his eye. "And when I look up, there's a guy pointing a gun at me," he tells me in March.

They searched his house, forcing his mother-in-law out of the shower at gunpoint and seizing all sorts of things, including the art off the walls and his wife's jewelry. "When I got out of prison—I was in prison for eight days—I come back and I'm working on a story, I'm in my office, and I reach for an accordion file. And in the accordion file, I find this," he later told me, brandishing a paper fan. It said: "TODAY'S FBI. IT'S FOR YOU."

It was the beginning of a yearslong legal war for Lacey, Larkin, and several former staffers at Backpage.

Ferrer, the former CEO, accepted a plea deal that saw him copping to "conspiracy to facilitate prostitution" and agreeing to testify against his former colleagues. Ferrer would eventually claim in court that Backpage helping law enforcement was merely "misdirection" and a "public relations stunt." But a binder full of thank-yous and commendations from law enforcement officers, and a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report from 2021, suggest that whatever the motive, Backpage did a lot of good anyway.

Following their arrest, Lacey and Larkin were forbidden from leaving Maricopa County without permission and forced to wear ankle monitors. Their jury trial would take years to get to, partly because of the COVID-19 pandemic and partly because prosecutors kept throwing up roadblocks.

"One of the tactics that the government employed was trying to starve Backpage out by seizing its assets, seizing bank accounts, and making it impossible for Backpage to pay its lawyers," Corn-Revere says.

Meanwhile, prosecutors kept pushing the idea that this was asex trafficking case, even though the actual charges were facilitating prostitution, money laundering, and conspiracy.

"Prosecutors were intent on making this sound like a trafficking case when it wasn't a trafficking case," says Corn-Revere. And they "have continued to try and limit the defenses the defendants can use."

The first trial, in 2021, was declared a mistrial after prosecutors and their witnesses kept emphasizing child sex trafficking although the judge ordered them not to. A subsequent trial was scheduled for summer 2023. In a group of motions filed in June 2023, the government made a series of demands that tried to take away every defense that the Backpage team intended to make to convince a jury the prosecution was misguided. The prosecutors asked the judge to bar the defense from any mention of the First Amendment or free speech, even though the First Amendment is at the center of the case. Prosecutors also asked the judge to block the defense from talking "about the legality or illegality of any advertisement," referencing Section 230, or talking about the fact that myriad lawyers over the years had advised them that the site was operating in the confines of the law.

The government further wanted to bar the defense from talking about how state attorneys general urged online classifieds to charge money for adult ads (which Backpage did not do at first), or from mentioning previous cases where the courts ruled in Backpage's favor. The state also asked to bar any references to the 2021 mistrial, or to Lacey and Larkin's career in journalism, or to the defendant's families.

Judge Humetewa partially rejected the request to bar references to the First Amendment, but granted most of the other motions to limit how Lacey and colleagues could defend themselves.

A little over a week before the trial was scheduled to begin, Larkin took his own life.

"You know, we had been through so much, and we always went through it together," says Lacey. "I literally screamed when I heard about [Jim's suicide] on the phone….He's gone, and he shouldn't be. He just shouldn't be."

Larkin "had been told repeatedly by every lawyer, not just most lawyers, but by every lawyer that looked at Backpage that it was legal, OK?" says Lacey. "And here he was facing a really harsh road in prison. And…I think he just ran out of hope."

Corn-Revere says "the government has Jim Larkin's blood on its hands."

Prosecuting Real Sex Trafficking Gets Harder

It's hard to argue Backpage's shutdown or FOSTA's passage makes anyone safer.

Online ads for sex work didn't disappear; they just migrated. Newer platforms often "host servers abroad, reside abroad, use offshore bank accounts and financial institutions, or introduce third parties to attempt to obscure or distance themselves from the day-to-day operation of their platforms," as a 2021 GAO report stated.

"The FBI's ability to identify and locate sex trafficking victims and perpetrators was significantly decreased following the takedown of Backpage.com," the GAO report says. It also notes adult ads have migrated beyond platforms specifically welcoming them, flooding "social media, dating, hookup, and messaging/communication platforms." The dispersed nature of this new world of sex ads also makes things more difficult for law enforcement.

Sex workers themselves suddenly lost a valuable tool that allowed them to enjoy more independence and face less risk. Once Backpage went down, "there was panic from everyone I knew," sex worker rights advocate Phoenix Calida told me last year. "People still had to work but couldn't advertise or screen. They went missing…got abused…got ripped off by clients."

"You saw a huge…uptick in street-based prostitution, asking for money at bars," says Kaytlin Bailey, a comedian, former sex worker, and founder of Old Pros, a nonprofit that aims to advance sex worker rights by telling the stories of sex workers throughout history. "This is not the way that sex workers want to do business. We want to be able to openly advertise our services and explicitly negotiate consent with a willing customer."

A June 2024 study in the journal Social Sciences—"440 Sex Workers Cannot Be Wrong: Engaging and Negotiating Online Platform Power"—found sex workers experienced a host of downstream negative effects after losing access to various online platforms.

"While the effects of the demolition of Backpage were awful for sex workers, I think the most devastating effects are those which will proceed from the terrible precedents the persecution set," sex worker and author Maggie McNeill said last year. "By wantonly destroying an internet business…based [on] a rather bizarre legal theory of vicarious liability, the government has demonstrated that it cannot and will not be constrained by Section 230, the First Amendment, or even the venerable principle of presumption of innocence."

Since the shutdown of Backpage, politicians have used similar techniques to go after social media companies, including Meta, TikTok, Discord, and Snapchat. "It appears that you're trying to be the premier sex trafficking site," Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R–Tenn.) told Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg during a January 2024 Senate judiciary committee hearing on protecting children online.

Officials summon sexual exploitation as an excuse for policies that harm privacy and free speech for everyone, such as destroying end-to-end encryption, censoring content that could be considered "harmful" to minors in any way, and requiring all social media users to show a government ID in order to maintain their account.

"It's the same playbook" used with Backpage, says Masnick; "not an attempt to deal with the real problems" but "an attempt to demonize someone and some company because it gets headlines; it gets attention. They can pretend they're doing something when they're really making the problem worse."

"It was easy for them to do it with Larkin and Lacey," adds Masnick. "It would be easy for them to do it to Zuckerberg or whoever else they want to go after."

Lacey's Never-Ending Trial

Before Larkin committed suicide, Lacey recalls that his old friend told him: "Look, you're going to be all right in this. You didn't have anything to do with Backpage. But my name is all over every single document having to do with Backpage."

Lacey was the editorial guy, not the business guy. Backpage wasn't his baby. His lawyers emphasized that in sentencing proceedings.

When Larkin was still alive, this was not a point I ever heard Lacey bring up. Both men just emphasized that Backpage ads were protected by the First Amendment, Backpage was protected by Section 230, and lawyers had advised them repeatedly they were in the clear.

Neither man used arguments that left Larkin holding the bag when both still faced legal jeopardy. Only after Larkin was no longer on trial did Lacey begin emphasizing the obvious that wasn't me defense. Deflecting the guilt only off of himself seems to be something alien to the nature of his relationship with his late business partner, something that could be said aloud only after Larkin was gone.

In September 2023, Lacey and the remaining Backpage defendants were put on trial again. Two of them—former operations manager Andrew Padilla and former assistant operations manager Joye Vaught—were fully acquitted. "My client should have never been in this case," Vaught's attorney, Joy Bertrand, told reporters. "She was charged and pressured to cooperate and assist the government, and she had the courage to say no."

Former executives Jed Brunst and Scott Spear were both acquitted on multiple counts and convicted on multiple counts.

A jury found Lacey guilty on just one of the 86 counts against him: international concealment money laundering. Lacey has appealed the conviction, which stems from the fact that he parked proceeds from the sale of Backpage in an offshore trust for his sons.

"This is not a case where the defendant went off on his own to hide an asset," his lawyers said in a sentencing memo. He created the Hungarian account after "federal law enforcement officers had visited his banks and suggested to those banks that it would be bad for their reputation to have him as a client, which then resulted in the banks terminating their relationship with him." And "the entire transaction was papered and executed by counsel. Michael did not hide anything from his counsel….There was no intent to conceal, and no actual concealment, but rather, an intent to disclose and actual disclosure."

While finding Lacey guilty of concealment of money laundering, the jury also acquitted him of one money laundering charge. On the remaining 84 counts, it couldn't reach a decision. With regard to those counts, a mistrial was again declared.

Judge Humetewa subsequently tossed 50 of the remaining counts against Lacey, finding the prosecution "insufficient of evidence to support convictions" of these counts. (The judge also acquitted Brunst and Spears of some counts on which they had been convicted.)

That still leaves 34 counts on which prosecutors could try Lacey again—and they've signaled they intend to do so.

That prosecutors might bring Lacey to trial a third time, even though he'll already be in prison for five years, calls to mind something Larkin told me in 2023. If there's one overarching lesson of the Backpage saga, this seems to be it.

"If the government decides to point its finger at you, there's really no question that they're going to try to ruin you," he said. And "given the system and the way it's set up," chances are high it will succeed.

Photo Credits: Cliff Owen/AP Photos; Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom; Photos: Jonathan Ernst/REUTERS/Newscom; Jesse Rieser; Russ Smith; Scott Carson/ZUMAPRESS; Photos: Moose/AdMedia/Newscom; Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Newscom; Chris Maddaloni/CQ Roll Call/Newscom; Mario Anzuoni/REUTERS/Newscom; Ricardo Watson/UPI/Newscom; Richard Messina/Hartford Courant/MCT/Newscom; © Sacramento Bee/ZUMApress/Newscom; Photos: Hector Amezcua/Sacramento Bee/TNS/Newscom; Photos: Jason Reed/REUTERS/Newscom; Photos: Armando Arorizo/EFE/Newscom; Courtesy Everett Collection/Newscom; Rod Lamkey/CNP/Polaris/Newscom; Photos: Rod Lamkey/CNP/Sipa USA/Newscom; Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Newscom; Photos: Jimin Kim/SOPA Images/Sipa USA/Newscom; Additional Photos Provided By: Michael Lacey, Stephen Lemons

Music Credits: "Behind Every Decision," "A Journey's Epilogue," and "Murmuring," by Yehezkel Raz via Artlist; "Goodbyes," by Ian Post via Artlist; "Strange Connection," and "Momento," by Nobou via Artlist; "Kiss of Death," and "Evidence," by Kadir Demir via Artlist; "Fundy," by REW via Artlist; "Turning Point," and "Marakana" by Alon Peretz via Artlist; "Eureka," by Ardie Son via Artlist; "Bark Technology" by YesNoMaybe via Artlist; "Wok Like a Cowboy," by Ofer Koren via Artlist; "Dust and Danger," by The North via Artlist; "Odd Numbers," by Curtis Cole via Artlist; "Attacca," and "Eris" by Brianna Tam via Artlist;

- Video Producer: Paul Detrick

- Video Editor: Paul Detrick

- Audio Production: Ian Keyser

- Color Correction: Cody Huff

- Motion Graphics: Paul Detrick

- Camera: Isaac Reese

- Camera: Clay Haskell

- Camera: Haley Saunders

- Camera: James Lee Marsh

Show Comments (22)