Why Kamala Harris Won't Be Asked About the Suicide of a Newspaperman She Persecuted

When it comes to conflicts with people engaged in unpopular or disfavored speech, too many journalists side with the feds.

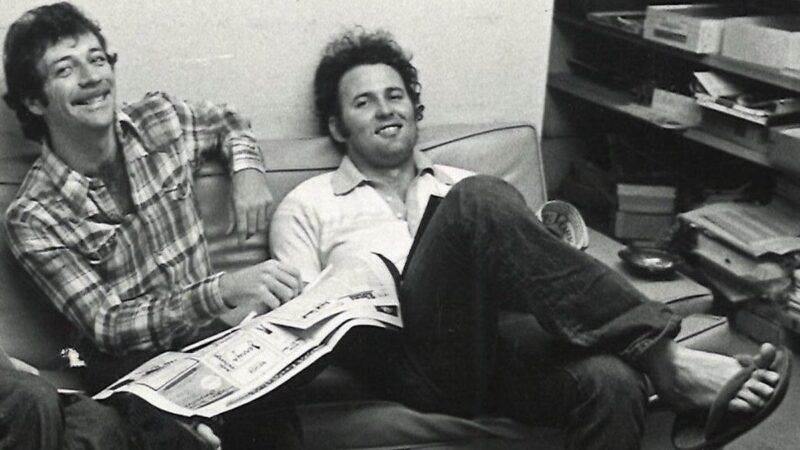

The sitting vice president, shortly before moving to Washington, D.C., successfully scapegoated through heavily publicized if legally unsuccessful pimping prosecutions a career newspaperman who last week shot himself to death at age 74 rather than sit through yet another prostitution-facilitation trial that he insisted to his dying days was an attack on free speech.

Yet the chances of Kamala Harris being asked this week—or any week—about the late James Larkin, or her starring role in the demonization of his and Michael Lacey's online classified advertising company Backpage as "the world's top online brothel," are vanishingly small. That's because people have a natural revulsion toward anything associated—however falsely—with child prostitution or sex trafficking, true. But it also stems from something far less excusable: When it comes to conflicts between the feds and those from the professionally unpopular corners of the free speech industry, journalists have been increasingly taking the side of The Man.

You could see this dynamic in stark relief last month in the elite-media response to U.S. District Court Judge Terry Doughty's Independence Day injunction against the federal government from pressuring social media companies to censor individuals for allegedly spreading "misinformation." As catalogued at Reason by Robby Soave, J.D. Tuccille, Jacob Sullum, and Robert Corn-Revere, and as I experienced during a bizarre panel discussion on CNN, the default journalistic reaction was anxiety that the ruling (in the words of the New York Times news department) "could curtail efforts to combat false and misleading narratives about the coronavirus pandemic and other issues." Sure, there may be First Amendment implications, but, well, have you seen that dangerous whackaloon Alex Berenson?

Far too often, journalists reserve their free speech defenses for people they actually like. And man, did they not like Jim Larkin and Mike Lacey.

This antipathy for Larkin/Lacey and the New Times alt-weekly chain the duo launched in Phoenix was obvious long before politicians began moving on from Craigslist to Backpage in their morally panicked crusade against technology companies that allegedly promote "sex trafficking." (I use quotation marks here not to intimate that sex trafficking does not exist, but rather that, as Reason's Elizabeth Nolan Brown has documented better than any living reporter, the term is overwhelmingly deployed by politicians and law enforcement to describe and punish conduct that has nothing whatsoever to do with forcing unwitting adults, let alone minors, into the sex business.)

The New Times honchos—especially Lacey, who was always the more public and pugilistic face of the franchise—were resented because they threw sharp elbows at both the graybeard alternative weeklies to their left and at the big-city dailies that were originally to their right but then tacked over time to the kind of bloodless lefty respectability space inhabited by NPR. The New Times papers hurled buckets of snark onto anyone perceived as Establishment, which pissed off boomer lefty journalists almost as much as elected Republican officials such as Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio and Arizona Sen. John McCain.

The New Times "view of who was the establishment and who [was] the outsider," sniffed LA Weekly windbag Harold Meyerson in 2003, "was classically neocon." (The game of pin-the-inaccurate-political-insult on the New Times never did fall out of fashion.)

Having mocked, then beaten, then eventually subsumed a Village Voice Media chain revered for its foundational role in postwar alternative journalism, Lacey and Larkin and co. found themselves relatively friendless during various scrapes with the legal system. When the independent hippie alt-weekly San Francisco Bay Guardian won a lawsuit in 2008 against the New Times–owned SF Weekly for "predatory pricing" of advertising (yes, one free paper sued another free paper over charging lower ad rates), and when that $21 million settlement (after having been tripled by the presiding judge) was upheld in 2010, I noted that "the journalistic thumbsucker community outside of the Bay Area has been almost completely silent about this potentially momentous precedent."

You can almost hear the journalistic eyerolls at Backpage's frequently successful series of legal defenses that the third-party speech and commerce that the now-defunct company facilitated were protected under Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act of 1996, i.e., "the Internet's First Amendment."

"As Trial for Backpage's Founders Begins," snarked a September 2021 Gizmodo headline, "Their Free Speech Defense Is Flailing." (The case was declared a mistrial less than a week later due to prosecutorial misbehavior.) The Washington Post in 2022 published a laudatory review of prosecutor Maggy Krell's book Taking Down Backpage: Fighting the World's Largest Sex Trafficker, with Section 230 treated as a deviously exploited loophole. "Krell and her fellow crusaders," concluded E.J. Graff, then–managing editor of the Post's Monkey Cage blog, "are rightly proud of the strides they've made in cracking down on this scourge."

This is not to say that there haven't been good (and appropriately skeptical) examinations of the Backpage side of the story, though it's interesting to note that they often come from people who used to work for the New Times chain. And there has been a smattering of free-speecher support and outrage over the years, including last week from TechDirt's Mike Masnick.

But the overarching journalism-industry response to the past seven years of Backpage founders being hounded by ambitious politicians and prosecutors and thrown into courtroom cages; their family members being pulled out of the shower; their bank accounts seized; their ankle bracelets affixed; and now one of the defendants offing himself has been studious indifference and silence. You will see 100 times more ink spilled this year on chimerical right-wing book bans than you will on the vice president's scapegoat blowing his brains out.

Journalists tend to be pretty good about looking backward through the decades and recognizing that, Oh shit, we kind of went overboard during that whole Satanic Panic thing. While better late than never, such correctives should lend urgency to the quest of finding injustices that are depriving people's liberty right the hell now.

Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht is still serving two life sentences in federal prison. President Joe Biden is sitting on a backlog of approximately 19,000 clemency petitions, most for nonviolent crimes and/or violations of laws that no longer exist. And Mike Lacey still faces trial, scheduled for later this month. It's too late for Jim Larkin's kids to get their dad back, but it's never too late for people in the free speech business to recognize that one of their own is getting railroaded. I just wouldn't bet on it.

Show Comments (87)