A Federal Judge Explains Why Trump Can't Jail Legislators for Producing a Video That Offended Him

U.S. District Judge Richard Leon notes that Sen. Mark Kelly's comments about unlawful military orders were "unquestionably protected" by the First Amendment.

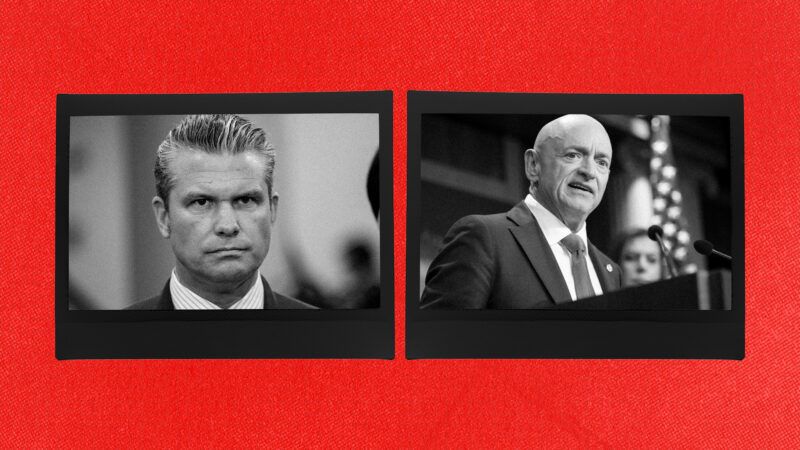

When Sen. Mark Kelly (D–Ariz.) reminded U.S. military personnel that they "can refuse illegal orders," a federal judge in Washington, D.C., ruled on Thursday, his speech was "unquestionably protected" by the First Amendment. U.S. District Judge Richard J. Leon, a George W. Bush appointee, granted Kelly's request for a preliminary injunction that temporarily bars Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth from pursuing penalties against the senator, a retired Navy captain, based on public comments that Hegseth deemed "prejudicial to good order and discipline in the armed forces."

Leon concluded that Kelly, who in November joined five other Democratic members of Congress in producing a video about the duty to disobey unlawful military orders, was likely to prevail in his claim that Hegseth had retaliated against him for his constitutionally protected speech. The video irked President Donald Trump, who said the six legislators "should be ARRESTED AND PUT ON TRIAL." Although the Justice Department has tried to deliver on that threat, a federal grand jury this week rejected a proposed indictment. Leon's opinion explains why any such prosecution would be blatantly unconstitutional.

All of the lawmakers whom Hegseth dubbed "the Seditious Six" had served in the armed forces or intelligence agencies. But Kelly was the only one who had retired with a pension, making him potentially subject to discipline under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. On January 5, Hegseth issued a letter of censure against Kelly, saying he had "engaged in a sustained pattern of public statements that characterized lawful military operations as illegal and counseled members of the Armed Forces to refuse orders related to those operations."

Kelly's statements, Hegseth said, constituted "conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline in the armed forces and conduct unbecoming an officer." The evidence, he said, was sufficient to "reopen the determination of your retired grade," a process that could reduce Kelly's rank and pension. Hegseth warned Kelly that "you may subject yourself to criminal prosecution or further administrative action" if "you continue to engage in conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline."

In addition to the video, which reiterated the well-established principle that service members "have a duty to disobey" orders that are "manifestly illegal," the letter cited several other statements that irritated Hegseth. On November 21 and November 23, Hegseth complained, "you criticized military leadership for 'firing admirals and generals' and surrounding themselves with 'yes men,' asserting you would 'ALWAYS defend the Constitution.'" A couple of days later, "you stated that intimidation would not work and called your advice to refuse orders 'non-controversial.'"

The following month, Hegseth wrote, "you continued to accuse me and senior military officers of war crimes and to frame resistance to lawful orders as protecting against overreach." In particular, Kelly criticized Trump's murderous military campaign against suspected drug boats, which became freshly controversial in late November and early December after it was revealed that the inaugural attack on September 2 included a follow-up missile strike that obliterated two survivors as they clung to the smoldering wreckage.

During a November 30 interview on CNN, Kelly was asked whether "a second strike to eliminate any survivors" would constitute "a war crime"—specifically, a violation of the rule against attacking shipwrecked sailors. "It seems to," Kelly said. "I have got serious concerns about anybody in that chain of command stepping over a line that they should never step over." He added that he would have refused to follow such an order.

Commentary on such matters is exactly what you would expect from a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Yet according to Hegseth, it was an offense justifying "administrative action" and possibly "criminal prosecution." To justify that take, he argued that Kelly was still subject to military discipline, including speech restrictions that would be unconstitutional if they were applied to civilians.

"Secretary Hegseth relies on the well-established doctrine that military servicemembers enjoy less vigorous First Amendment protections given the fundamental obligation for obedience and discipline in the armed forces," Leon writes. "Unfortunately for Secretary Hegseth, no court has ever extended those principles to retired servicemembers, much less a retired servicemember serving in Congress and exercising oversight responsibility over the military. This Court will not be the first to do so!"

That point was crucial because the government offered no other justification for punishing Kelly. "Under ordinary First Amendment principles, the speech at issue here is unquestionably protected speech," Leon notes. "Speech 'on matters of public concern' lies at the core of First Amendment protection. This broad category includes speech on 'any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community' or any 'subject of general interest and of value and concern to the public.' It includes 'opposition to national foreign policy,' and even 'vehement, caustic, and…unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.'"

Hegseth's letter "identifies a 'sustained pattern of public statements' including, primarily, the November 18 video in which Senator Kelly stated that members of the armed forces 'can refuse illegal orders,'" Leon writes. "It also identifies the Senator's statements characterizing certain military orders as 'unlawful' and criticizing military leadership. Under any reading of the law, Senator Kelly's statements constitute 'speech on matters of public concern' and are therefore 'entitled to special protection.'"

The defendants "rest their entire First Amendment defense on the argument that the more limited First Amendment protection for active-duty members of the military extends to a retired naval captain," Leon says. But he notes that the operational concerns underlying special speech restrictions for active-duty service members, which the Supreme Court upheld in the 1974 case Parker v. Levy, do not apply to retirees.

"As applied to a sitting Member of Congress, the Parker rule has even less force!" Leon adds. Representative government, after all, requires legislators to take controversial positions on public policy issues, and Kelly's job also involves oversight of Hegseth and other Pentagon officials. "Between the lack of precedent extending Parker outside the

context of active-duty military and the heightened free speech protection for legislators," Leon says, "Senator Kelly's speech must receive full First Amendment protection."

If so, any attempt to prosecute Kelly for that speech would be unconstitutional, and the same goes for the other legislators who participated in the video that offended Trump and Hegseth. Jeanine Pirro, the Trump-appointed U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, nevertheless argued that Kelly and the others had committed a federal felony by reiterating a principle that Kelly accurately described as legally uncontroversial.

The grand jury did not buy it. Neither should any American who cares about freedom of speech.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Which order was unlawful you dishonest cunt?

Also, how many times do we have to tell you to not rape young Boys? You'd think at some point we wouldn't have to remind you for your own good it's illegal and there are consequences.

Which order was unlawful

Doesn't matter. Still free speech.

Which order was unlawful you dishonest cunt?

The more salient question is what was said that was illegal?

No, which order was illegal?

If you feel the need to remind someone of something then there is either a reason or you're just engaging in false light libel, or slander given the medium.

No, which order was illegal?

Why does it matter? What does that have to do with free speech rights? Are they jackasses? Yes. Did they do anything illegal? You still haven't shown that they have.

Sorry dumbass but when you're sowing division in the military ranks and and setting up interference with the chain of command over nothing you just might have a problem within the military. You're pretending he's just some dude spouting off in a bar and not retired military telling the military on a national platformto defy the CiC. There is a word for that.

Why is so much of your tactics pretending not to understand the obvious?

Actually it’s not. He wasn’t being charged with a crime, he was being investigated by the Secretary of war as a retired Navy general.

Do you think people in the military have a 1A right to sow division in the military?

So, you're saying that what he said was illegal, or that it doesn't matter whether or not it was?

Do you think people in the military have a 1A right to sow division in the military?

Attacking the boats was clearly illegal. Murdering survivors is even more illegal. But that does not matter. The video had no need to go into specifics.

No it was the. Even the seditionists didn't claim it was.

Reminder: Hegseth said in 2016 that the military should refuse to follow unlawful orders.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/dec/08/hegseth-unlawful-orders-trump-fox-interview

From the video, he said:

“If you are doing something that is completely unlawful and ruthless then there is a consequence for that. That’s why the military said it won’t follow unlawful orders from their commander in chief. There’s a standard; there’s an ethos; there’s a belief that we are above so many things are enemies or others would do.”

I guess that makes Hegseth a seditionist? I mean, he couldn't identify specifically which order he thought was unlawful! How dare he undermine the military chain of command like that!

And just to be clear:

I believe both Hegseth and the six Democratic representatives had every right to say whatever they want about the military not following unlawful orders, that it wasn't sedition when Hegseth did it and it wasn't sedition when the Democrats did it, and there is absolutely no requirement to specifically identify which order someone thinks is unlawful in order for that person to have the RIGHT to say whatever they want about the topic.

It was a stupid thing to do.

Stupid is not the same as illegal.

How so? It told the military that they are not alone if they need to disobey an illegal order.

Did they also tell them to be sure to wipe their asses after taking a shit?

You are a dishonest POS. The hypothetical order in the Hegseth example is the deliberate murder of the families of terrorists not an order to carry out their primary charge in a normal manner. What is the unlawful order even suggested by Trump in regards to ICE this time? Refusing to commit war crimes is fine, refusing to do your job because you're #resistence is not.

Also, it is wrong to rape kids Jeff so please refrain.

Many an unquestionable fact at the district level becomes bullshit at the supreme court.

They control the presidency now. They also control the NCAA apparently.

This isn’t a 1A issue at all hack.

I had a chat with Poe Assistant about this.

https://poe.com/s/uyQ28bJJPL1sH7nSfFC1

ooooooo

A Break from Civil‑Military Norms: Abu Ghraib, Afghanistan, and the “Refuse Illegal Orders” Video

The controversy over the “refuse illegal orders” video is not primarily about criminal law. It is about civil‑military norms. Whether one supports or opposes the lawmakers’ message, the episode marks a departure from how Congress has historically handled moments of military crisis and executive controversy.

1. Abu Ghraib (2004): Confirmed Abuse, Institutional Response

The Abu Ghraib scandal involved documented detainee abuse by U.S. personnel. It triggered global outrage, damaged U.S. credibility, and raised serious questions about command responsibility and interrogation policy.

Members of Congress sharply criticized the Bush administration and Pentagon leadership. They held hearings, demanded investigations, and pressed for accountability. The scandal resulted in court‑martials and formal reviews.

But despite the severity of the misconduct — and despite clear violations of military law — Congress did not broadcast direct partisan messages addressed to rank‑and‑file troops urging them to reinterpret or resist command authority. Lawmakers criticized leadership publicly and institutionally, but they did not step into the command relationship by speaking directly to service members in that way.

2. Afghanistan Withdrawal (2021): Intense Controversy, Institutional Critique

The chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan prompted widespread criticism of both the Biden administration and military leadership. There were arguments that public trust in the military had been damaged. Hearings were held, and political rhetoric was sharp.

Yet even in that environment, members of Congress did not produce coordinated video appeals addressed specifically to active‑duty troops encouraging them to scrutinize or resist executive authority. Criticism flowed toward the president, the secretary of defense, and senior commanders — not toward rank‑and‑file personnel as a direct audience.

Again, institutional channels were used. The norm of avoiding direct partisan engagement with the enlisted force held.

3. The “Refuse Illegal Orders” Video: Direct Messaging to Troops

By contrast, the more recent video was explicitly directed at “members of the military” and the intelligence community. It was framed with a political accusation that the administration was “pitting” uniformed professionals against American citizens, and it urged service members to refuse unlawful orders.

Importantly, no specific unlawful order was identified at the time. When later questioned, Sen. Mark Kelly did not cite a concrete directive but instead defended the message as preventative.

The legal principle invoked — that troops must disobey manifestly illegal orders — is well established. But the method and framing were different from prior crises: this was a direct appeal to uniformed personnel, embedded in a partisan critique of the sitting president.

4. Why the Distinction Matters

The United States relies on a politically neutral professional military and a clear chain of command under civilian control. Members of Congress unquestionably have oversight authority over the armed forces. But historically, even during confirmed misconduct or severe policy failures, lawmakers have exercised restraint in communicating directly with the rank and file.

The pattern across Abu Ghraib and Afghanistan suggests a longstanding norm:

Criticize policy.

Investigate leadership.

Use hearings and public debate.

Avoid direct partisan messaging aimed at active‑duty personnel.

The recent video represents a departure from that pattern. It shifted from criticizing executive decision‑making to directly addressing troops about how to evaluate presidential authority, without tying that appeal to a specific unlawful order.

5. The Core Claim

Two propositions can coexist:

The video was protected political speech and should not be criminalized.

It marked a break from traditional congressional restraint in civil‑military relations.

The comparison to Abu Ghraib and Afghanistan sharpens the point. In episodes involving documented illegality or significant operational failure, Congress criticized leaders but did not directly insert itself into the command relationship. Doing so in a preventative, anticipatory context — and in explicitly partisan terms — raises legitimate questions about whether an important civil‑military norm has shifted.

That is the heart of the argument.