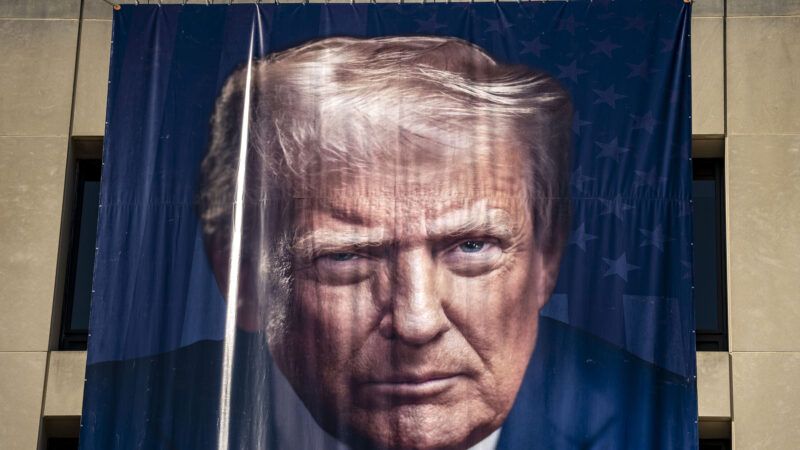

The Federal Circuit's Tariff Ruling Highlights the Audacity of Trump's Power Grab

Seven judges agreed that the president's assertion of unlimited authority to tax imports is illegal and unconstitutional.

In ruling against the sweeping tariffs that President Donald Trump purported to impose under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit did not settle the question of whether that law authorizes import taxes. Nor did it uphold the injunction that the Court of International Trade (CIT) issued against the tariffs on May 28. But the Federal Circuit agreed with the CIT that the tariffs are unlawful, and its reasoning highlights the audacity of Trump's claim that IEEPA empowers him to completely rewrite tariff schedules approved by Congress.

The decision addresses two challenges to Trump's tariffs, one brought by several businesses and one filed by a dozen states. Both sets of plaintiffs argued that Trump had illegally seized powers that belong to Congress.

The Constitution gives Congress, not the president, the power to "lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises." And although Congress has delegated that authority to the president in "numerous statutes," the Federal Circuit notes in an unsigned opinion joined by seven members of an 11-judge panel, it has always "used clear and precise terms" to do so, "reciting the term 'duties' or one of its synonyms." Furthermore, Congress always has imposed "well-defined procedural and substantive limitations" on the president's tariff powers.

IEEPA, by contrast, "neither mentions tariffs (or any of its synonyms) nor has procedural safeguards that contain clear limits on the President's power to impose tariffs." Yet under Trump's reading of the statute, it empowers him to impose any tariffs he wants against any country he chooses for as long as he deems appropriate, provided he perceives an "unusual and extraordinary threat" that constitutes a "national emergency" and avers that the import taxes will "deal with" that threat.

To justify his tariffs, Trump declared two supposed emergencies, one involving international drug smuggling and the other involving the U.S. trade deficit. The former "emergency," he said, justified punitive tariffs on goods from Mexico, Canada, and China, with the aim of encouraging greater cooperation in the war on drugs. The latter "emergency," he claimed, justified hefty, ever-shifting taxes on imports from dozens of countries, which he implausibly described as "reciprocal."

Leaving aside the question of whether it makes sense to characterize drug trafficking and trade imbalances, both of which are longstanding phenomena, as "unusual and extraordinary" threats, Trump's attempted power grab is striking even for him. "Since IEEPA was promulgated almost fifty years ago, past presidents have invoked IEEPA frequently," the Federal Circuit notes. "But not once before has a President asserted his authority under IEEPA to impose tariffs on imports or adjust the rates thereof. Rather, presidents have typically invoked IEEPA to restrict financial transactions with specific countries or entities that the President has determined pose an acute threat to the country's interests."

Trump claims to have discovered a heretofore unnoticed tariff power in an IEEPA provision that authorizes the president to "regulate…importation." And that power, he avers, is not subject to any "procedural and substantive limitations" except for the pro forma requirement that he declare a national emergency based on a foreign threat. As the Federal Circuit dryly observes, "it seems unlikely that Congress intended, in enacting IEEPA, to depart from its past practice and grant the President unlimited authority to impose tariffs."

Trump's assertion of that authority "runs afoul of the major questions doctrine," the Federal Circuit says. According to the Supreme Court, that doctrine applies when the executive branch asserts powers of vast "economic and political significance." In such cases, "the Government must point to 'clear congressional authorization' for that asserted power," the appeals court notes. "The tariffs at issue in this case implicate the concerns animating the major questions doctrine as they are both 'unheralded' and 'transformative.'" The Supreme Court "has explained that where the Government has 'never previously claimed powers of this magnitude,' the major questions doctrine may be implicated."

The Federal Circuit was unimpressed by the government's citation of United States v. Yoshida International, a 1975 case in which the now-defunct Court of Customs and Patent Appeals approved a 10 percent import surcharge that President Richard Nixon had briefly imposed in 1971 under the Trading With the Enemy Act (TWEA). Although Nixon relied on a different statute, the government's lawyers noted, the court concluded that the phrase "regulate importation" in TWEA encompassed tariffs.

Even assuming that conclusion was correct, the Federal Circuit says, Yoshida "does not hold that TWEA created unlimited authority in the President to revise the tariff schedule, but only the limited temporary authority to impose tariffs that would not exceed the Congressionally approved tariff rates." Trump, by contrast, claims IEEPA gives him carte blanche to set tariffs, regardless of what Congress has said.

"The Government's expansive interpretation of 'regulate' is not supported by the plain text of IEEPA," the Federal Circuit says. "The Government's reliance on the ratification of our predecessor court's opinion in [Yoshida] does not overcome this plain meaning." The appeals court adds that "the Government's understanding of the scope of authority granted by IEEPA would render it an unconstitutional delegation."

Four judges agreed with the majority that IEEPA "does not grant the President authority to impose the type of tariffs imposed by the Executive Orders." But they went further in a separate opinion, arguing that the statute does not authorize the president to impose any tariffs at all.

As Reason's Eric Boehm notes, the appeals court nevertheless vacated the CIT's injunction and remanded the case for further consideration in light of the Supreme Court's June 27 decision in Trump v. CASA. In that June 27 ruling, the Court questioned universal injunctions that judges had issued in two birthright citizenship cases "to the extent that the injunctions are broader than necessary to provide complete relief to each plaintiff with standing to sue."

Although the Supreme Court "held that the universal injunctions at issue 'likely exceed the equitable authority Congress has granted to federal courts,'" the Federal Circuit notes, "it 'decline[d] to take up…in the first instance' arguments as to the permissible scope of injunctive relief. Instead, it instructed '[t]he lower courts [to] move expeditiously to ensure that, with respect to each plaintiff, the injunctions comport with this rule and otherwise comply with principles of equity' as outlined in the opinion. We will follow this same practice."

On remand, the Federal Circuit says, "the CIT should consider in the first instance whether its grant of a universal injunction comports with the standards outlined by the Supreme Court in CASA." The CIT, in other words, is tasked with deciding what sort of order is appropriate to grant the plaintiffs "complete relief." Alternatively, as Boehm suggests, Congress could intervene by asserting the tariff authority that Trump is trying to usurp.

Show Comments (49)