Trump, Who Wants To 'Straighten Out the Press,' Sues The Wall Street Journal Over 'Fake' Epstein Letter

Whatever the merits of this particular defamation claim, the president has a long history of abusing the legal system to punish constitutionally protected speech.

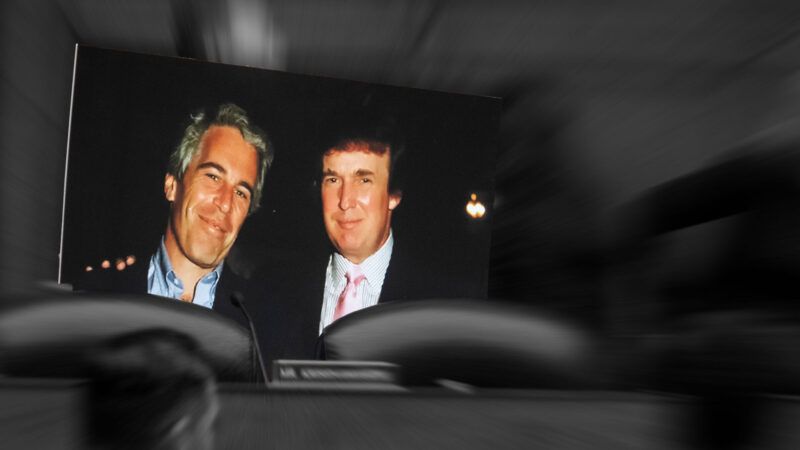

On Friday, President Donald Trump sued The Wall Street Journal for reporting that he contributed to a 2003 collection of letters marking the 50th birthday of financier Jeffrey Epstein, who was later charged with sex trafficking involving underage girls. Although it is well established that Trump was friendly with Epstein when that leather-bound set of birthday wishes was produced, Trump insists he did not write the "bawdy" letter described by the Journal, which he calls a "scam" and a "fake story."

Trump presented his defamation lawsuit, which he filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, as part of his broader campaign to rein in news outlets that he thinks have wronged him in one way or another. "I'm gonna sue The Wall Street Journal just like I sued everyone else," he told the paper when he was asked to comment on the story. "The Press has to learn to be truthful, and not rely on sources that probably don't even exist," Trump wrote on Truth Social, bragging that he had "already beaten George Stephanopoulos/ABC, 60 Minutes/CBS, and others."

The litigation to which Trump alluded covers a wide range. His defamation claim against ABC, for instance, was at least plausible, since it was based on demonstrably inaccurate reporting. But his lawsuit against CBS, which averred that the network committed consumer fraud by editing a pre-election 60 Minutes interview with former Vice President Kamala Harris in a way that made her seem slightly more cogent, was utterly frivolous. At this point, it is hard to say where Trump's complaint about the Journal's story falls on that spectrum. But in his determination to punish journalists who offend him, Trump typically has not paid much attention to the distinction between actionable torts and constitutionally protected speech.

A 'Terrific Guy'

In addition to Dow Jones, which owns the Journal, the defendants in Trump's lawsuit include News Corp, which owns Dow Jones; Rupert Murdoch, News Corp's majority owner and emeritus chairman; News Corp CEO Robert Thomson; and the two reporters who wrote the story about the Epstein letter, Khadeeja Safdar and Joseph Palazzolo. That article describes a letter "bearing Trump's name" that includes a typewritten imaginary conversation between him and Epstein. The text, Safdar and Palazzolo report, is "framed by the outline of a naked woman, which appears to be hand-drawn with a heavy marker. A pair of small arcs denotes the woman's breasts, and the future president's signature is a squiggly 'Donald' below her waist, mimicking pubic hair."

In the dialogue described by the Journal, the "Donald" character says "we have certain things in common," and the "Jeffrey" character concurs. Both men are "enigmas" who "never seem to age," they agree, and both understand there is "more to life than having everything." According to the Journal, the dialogue concludes with a message from "Donald": "A pal is a wonderful thing. Happy Birthday—and may every day be another wonderful secret."

Safdar and Palazzolo "falsely pass off as fact that President Trump, in 2003, wrote, drew, and signed this letter," Trump's lawsuit says. "The Article does not attach the purported letter, does not identify the purported drawing, nor does it show any proof that President Trump has anything to do with it. Tellingly, the Article does not explain whether Defendants have obtained a copy of the letter, have seen it, have had it described to them, or any other circumstances that would otherwise lend credibility to the Article. That is because the supposed letter is a fake and the Defendants knew it when they chose to deliberately defame President Trump."

Safdar and Palazzolo say their account is based on "documents" that they "reviewed," along with information from "people familiar with them." They imply that the documents included "pages from the leather-bound album" compiled for Epstein's birthday, although they also say "it isn't clear how the letter with Trump's signature was prepared." A Dow Jones spokeswoman said, "We have full confidence in the rigor and accuracy of our reporting."

If Trump did in fact write, or at least authorize, the birthday letter that the Journal attributed to him, the paper did nothing that would justify civil damages. But if that letter is a forgery, as Trump implies, he might have a valid defamation claim.

To support that claim, Trump has to show that the Journal acted with "actual malice," meaning it knowingly or recklessly reported something that was demonstrably false. The lawsuit complains that Murdoch and Thomson "authorized the publication of the Article after President Trump put them both on notice that the letter was fake and nonexistent." Since Trump and White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt both told the Journal the letter was "fake" prior to publication, a jury might reasonably conclude that the paper acted recklessly, assuming that Trump did not really write the letter. But Trump also has to prove that the Journal's claim was defamatory, which might be trickier.

Trump avers that the Journal's story, which "went viral" after it was published on Thursday evening, has caused him "overwhelming financial and reputational damages" that are "expected to be in the billions of dollars." But since Trump admits he was friends with Epstein in 2003 and for more than a decade prior to then, it is debatable whether the Journal's report caused any additional harm to the president's reputation, let alone damages adding up to "billions of dollars."

At the time, Epstein's celebrity friends also included former President Bill Clinton, billionaire Leslie Wexner, and Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who represented Epstein after his first arrest in 2006. Safdar and Palazzolo report that Wexner and Dershowitz joined Trump in contributing to the birthday album.

By itself, the claim that Trump participated in the birthday album merely confirms what the public already knew. "Is it defamatory that one millionaire sent a birthday card to another in 2003, before Epstein was discovered?" media attorney Damon Dunn wondered in an interview with Business Insider.

The imaginary conversation between Trump and Epstein is strange and ambiguous, but on its face it does not implicate Trump in anything more scandalous than his friendship with a man who would later become notorious as a sex offender. And the "bawdy" sketch seems mild compared to, say, Trump's recorded comments about grabbing women "by the pussy."

Trump's lawsuit faults the Journal for attempting to "inextricably link President Trump to Epstein," an "utterly disgraced" individual who committed suicide in federal custody six years ago. Yet Trump's own actions and statements already were enough to establish a link between the two men. Before they fell out in 2004 or so, Trump partied with Epstein in Palm Beach and Manhattan, posed for chummy photos with him, and repeatedly flew on his private jet.

"I've known Jeff for 15 years," Trump told New York magazine in 2002. Trump described Epstein as a "terrific guy" who was "a lot of fun to be with," adding: "It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side. No doubt about it—Jeffrey enjoys his social life." Defamation lawyer Chris Mattei suggested to Business Insider that the lawsuit could backfire if it results in discovery exploring Trump's relationship with Epstein, which "would be relevant to the question of whether or not it's likely Trump had any sort of role in this letter."

Trump's lawsuit asserts that the Journal's statements about him are "defamatory per se" because they "tend to harm" his reputation or "deter third persons from associating or dealing with him." But the complaint never really explains why the purported birthday letter falls into one of the categories of statements traditionally recognized as inherently damaging, such as claims that the plaintiff committed a serious crime, engaged in sexual misconduct, or behaved in a way incompatible with his profession.

'Fake News' Is Not a Tort

The ABC case, which resulted in a $16 million settlement last December, posed a similar question about reputational damage. On two broadcasts of his show This Week, George Stephanopoulos repeatedly asserted that Trump had been found civilly liable for "rape." Unlike the Journal's report on the Epstein birthday letter, the veracity of which is a matter of dispute, Stephanopoulos' claim was clearly inaccurate, since Trump had in fact been found liable for "sexual abuse." The jury in that civil case expressly concluded that the plaintiff, journalist E. Jean Carroll, had failed to prove her "rape" claim. If Trump's case against ABC had gone to trial, the network nevertheless could have argued that the difference between those two terms was not consequential enough to justify a damage award.

Although Trump's lawsuit against CBS also resulted in a $16 million settlement, the legal merits of that case were much weaker. Trump risibly claimed that, by editing a 60 Minutes interview with Harris to make her sound "less dumb," CBS had caused him at least $20 billion in damages. His lawsuit alleged violations of two statutes, the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act and the federal Lanham Act (which covers someone who "misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person's goods, services, or commercial activities") that plainly did not apply to the network's conduct. Paramount, which owns CBS, nevertheless decided to settle the case, starkly illustrating the pressure that a sitting president can bring to bear by combining frivolous legislation with implicit threats of adverse government action.

In his Truth Social post last week, Trump did not explicitly mention his equally ridiculous lawsuit against The Des Moines Register, which irked him by reporting the results of a 2024 election poll that erroneously predicted a Harris victory in Iowa. As in the case against CBS, Trump claims the newspaper committed consumer fraud by publishing a misleading story but fails to establish the requisite commercial relationship between him and the defendant. Trump's arguments in that case aim to carve out a "fake news" exception to the First Amendment, which would be a grave threat to freedom of the press.

If misleading journalism counted as actionable consumer fraud, news outlets would have to constantly worry about potentially ruinous litigation whenever their work might be characterized that way, which is almost always the case. Trump, who has promised to "straighten out the press," no doubt would welcome that speech-chilling outcome. But the prospect should alarm anyone who values the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment.

In Trump's long history of suing journalists, the predominant theme is vindictive retaliation, rather than obtaining compensation for legally cognizable damages. As a wealthy man, Trump could afford to pursue cases he had no hope of winning simply to inflict pain on people who said things he did not like. Even if the cases were ultimately dismissed, his enemies would suffer in the meantime.

In 1984, for instance, Trump sued Chicago Tribune architecture critic Paul Gapp for calling a Manhattan skyscraper proposed by Trump "aesthetically lousy" and "one of the silliest things anyone could inflict on New York or any other city." The thin-skinned developer demanded $500 million in compensation for those insults.

That seemed like a lot until Trump sought 10 times as much—$5 billion—in a 2006 lawsuit against Tim O'Brien, a financial journalist who had dared suggest that Trump was not worth as much as he claimed. Although Trump lost both of those cases, he later told The Washington Post he got what he wanted from his suit against O'Brien. "I did it to make his life miserable," he said, "which I'm happy about."

'A Libel Bully'

As First Amendment attorney Susan Seager noted in 2016, "Donald J. Trump is a libel bully." But "like most bullies, he's also a loser."

Trump and his companies "have been involved in a mind-boggling 4,000 lawsuits over the last 30 years and sent countless threatening cease-and-desist letters to journalists and critics," Seager reported. "But the GOP presidential nominee and his companies have never won a single speech-related case filed in a public court."

In addition to the lawsuits against Gapp and O'Brien, Seager noted Trump's 2013 lawsuit against comedian Bill Maher. That complaint was prompted by a joke mocking Trump's promotion of the calumnious claim that Barack Obama was not qualified to be president because he was not born in the United States.

In 2012, Trump made a video in which he promised to pay $5 million to the charity of Obama's choice if the president agreed to release his "college and passport records." In response, Maher said during an appearance on The Tonight Show in early 2013 that he would pay $5 million to the charity of Trump's choice if the orange-hued reality TV star provided proof that he was not "the spawn of his mother having sex with an orangutan." Trump thereupon sent Maher a copy of his birth certificate and demanded that he pay up. Receiving no response, Trump filed a $5 million breach-of-contract suit, which he withdrew, Seager noted, after it was "roundly ridiculed by the Hollywood Reporter."

Before he dropped that lawsuit, Trump sought to justify it by complaining about how mean Maher had been to him. "That was venom," he said on Fox News. "That wasn't a joke."

Seager thought Trump's litigation history underlined the need for state laws aimed at "strategic lawsuits against public participation" (SLAPPs). Anti-SLAPP laws, which have been enacted by 38 states and the District of Columbia, allow defendants who are sued based on constitutionally protected speech to seek a prompt dismissal and recover legal expenses from the plaintiff. But as Trump sees it, his track record shows it should be easier, not harder, to sue the objects of his ire. He aspires to "open up those libel laws" so that aggrieved public figures like him can sue irksome critics and "win money instead of having no chance."

Trump imagines a legal regime in which he could, for example, win damages from CNN for calling his claim that Joe Biden stole the 2020 presidential election "the 'Big Lie,' a concept tied to Adolf Hitler." Dismissing that lawsuit in 2023, U.S. District Judge Raag Singhal, a Trump appointee, deemed the implication to which Trump objected a matter of opinion, as opposed to a statement of fact.

"Being 'Hitler-like' is not a verifiable statement of fact that would support a defamation claim," Singhal noted. "CNN's statements, while repugnant, were not, as a matter of law, defamatory."

Trump also unsuccessfully sued CNN, The New York Times, and The Washington Post for statements related to the Russian government's role in the 2016 presidential election. Judges dismissed those lawsuits after concluding that they failed to adequately state defamation claims. When he dismissed the lawsuit against the Post in 2023, for example, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras noted that the Trump campaign had "failed to plead sufficient factual allegations supporting an inference of actual malice" with respect to one of the offending articles. The allegedly defamatory statement in another article cited by the campaign, Contreras added, constituted "nonactionable opinion."

'Our Press Is Very Corrupt'

Trump has been explicit about what he aims to accomplish with lawsuits like these. "We have to straighten out the press," he told reporters last December, explaining his motivation for suing CBS and the Register. "I'm doing this not because I want to," he added. "I'm doing this because I feel I have an obligation to….I shouldn't really be the one to do it. It should have been the Justice Department or somebody else. But I have to do it [because] our press is very corrupt."

As Trump sees it, the Justice Department should be policing the press to make sure it is telling the truth. Exactly how that would work is unclear: What statutes, specifically, would authorize the department to sue or prosecute news outlets for reporting that Trump views as inaccurate or unfair?

More to the point, any such action would be clearly unconstitutional. But Trump thinks he can achieve similar results by filing his own lawsuits.

After the settlement with Paramount was announced, Trump's lawyers presented it as a victory for all of us. "With this record settlement," they crowed, "President Donald J. Trump delivers another win for the American people as he, once again, holds the Fake News media accountable for their wrongdoing and deceit. CBS and Paramount Global realized the strength of this historic case and had no choice but to settle. President Trump will always ensure that no one gets away with lying to the American People as he continues on his singular mission to Make America Great Again."

You can judge for yourself whether the editing of the Harris interview qualified as "lying to the American People." But there is no question that it was protected by the First Amendment, which does not include an exception for journalism that strikes the president as misleading, biased, or unfair. Trump is avowedly determined to use any tools at his disposal to make sure "no one gets away" with covering the news in a way that offends him. That agenda, which goes far beyond vindicating legally plausible claims, is blatantly inconsistent with freedom of the press.

Show Comments (199)