After 100 Years, End the Open Fields Doctrine

Federal agents are allowed to search private property without a warrant under this Prohibition-era Supreme Court precedent.

In a decision issued at the dawn of Prohibition, the Supreme Court quietly gutted a freedom guaranteed in the Bill of Rights: the protection against unwarranted search and seizure. The 100th anniversary of that decision is a perfect time to kill the open fields doctrine.

In 1919, revenue agents spotted Charlie Hester selling a quart of moonshine outside his South Carolina home. When confronted, Hester and the buyer each dropped their jugs, which shattered but retained a portion of their contents. That allowed the agents to determine the jugs contained illegally distilled whiskey.

Hester challenged his arrest as a violation of the Fourth Amendment: The agents had hopped a fence and traipsed across a pasture, without a warrant, to get to him. In 1924, the Supreme Court sided with the government in Hester v. United States. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote for the majority that "the special protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their 'persons, houses, papers, and effects,' is not extended to the open fields." Ostensibly, Holmes' open fields doctrine held that a person's home and the "curtilage"—the area immediately surrounding the home—receive full Fourth Amendment protection, while the rest of one's property does not.

Holmes' decision is less than three pages long, but the damage it's caused to personal liberty and the right to be free from government intrusion has been huge.

The court affirmed Hester in 1984's Oliver v. United States, with Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. writing that "in the case of open fields, the general rights of property protected by the common law of trespass have little or no relevance to the applicability of the Fourth Amendment." Powell then went even further: "It is clear," he wrote in a footnote, "that the term 'open fields' may include any unoccupied or undeveloped area outside of the curtilage. An open field need be neither 'open' nor a 'field' as those terms are used in common speech." Powell contends that any bit of land not directly adjoining your primary residence is fair game for government agents to trespass at will.

In practice, the open fields doctrine allows wildlife agents to enter private property looking for violations, and in some cases agents have even planted cameras on private land—all without a warrant. "When Service officers enter onto open fields (not part of curtilage), their observations are reasonable under the Fourth Amendment," reads the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's policy manual.

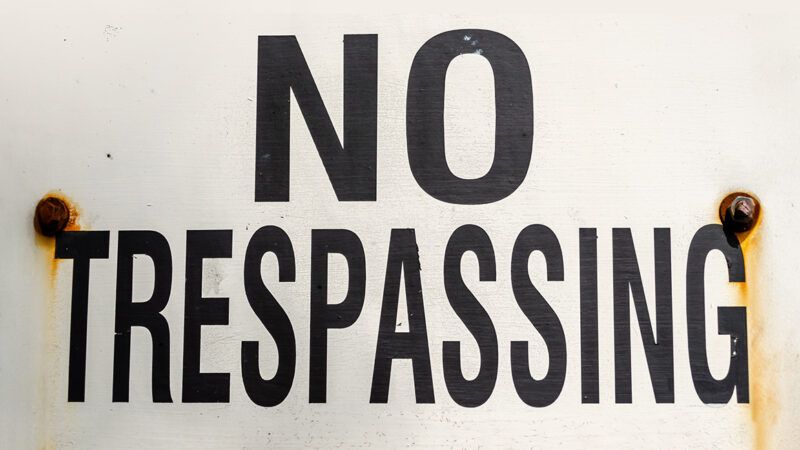

Steps taken to ensure privacy aren't enough. Powell wrote that "because fences or 'No Trespassing' signs do not effectively bar the public from viewing open fields, the asserted expectation of privacy in open fields is not one that society recognizes as reasonable." In fact, the search in Oliver involved Kentucky State Police officers driving onto private land until they reached a locked gate with a "No Trespassing" sign, then getting out and walking more than a mile down a footpath until they found a marijuana field—actions which the court affirmed.

Thankfully, some states provide their citizens greater protections than the Fourth Amendment does. In May 2024, the Tennessee Court of Appeals Western Section ruled against the state after wildlife agents planted cameras on private property to look for hunting violations, without a warrant. The unanimous court deemed that snooping "a disturbing assertion of power." Other courts have also determined over the years that individual state constitutions are more protective than the Fourth Amendment and have shot down some unwarranted trespasses that the open fields doctrine might have allowed.

But that doctrine subjects all American homeowners to potential trespass unless their state happens to provide greater protection—and even then, with no protection against the feds. In the absence of the doctrine, the Fourth Amendment would provide a level of protection against unwarranted searches as a matter of law, even on undeveloped land. Congress should abolish, or the Supreme Court should overturn, the open fields doctrine and give Americans breathing room on their own property.

Show Comments (28)