FDA Declines To Approve MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy as a PTSD Treatment

The FDA, which approved the protocols for the studies it now questions, is asking for an additional Phase 3 clinical trial, which would take years and millions of dollars.

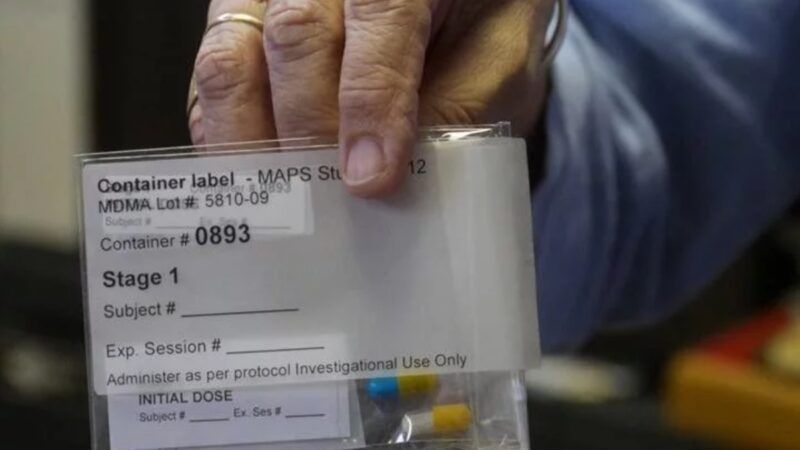

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declined on Friday to approve MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The agency has asked Lykos Therapeutics, which submitted the new drug application (NDA) in February, to conduct an additional Phase 3 clinical trial, which would take years and millions of dollars. It is a major setback that dismayed veteran advocates and others who see MDMA as a potentially life-changing psychotherapeutic catalyst for people struggling with longstanding psychological challenges that currently approved treatments have not adequately addressed.

"The FDA request for another study is deeply disappointing, not just for all those who dedicated their lives to this pioneering effort, but principally for the millions of Americans with PTSD, along with their loved ones, who have not seen any new treatment options in over two decades," said Amy Emerson, CEO of Lykos Therapeutics, a company created by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), in a press release. "While conducting another Phase 3 study would take several years, we still maintain that many of the requests that had been previously discussed with the FDA and raised at the Advisory Committee meeting can be addressed with existing data, post-approval requirements or through reference to the scientific literature."

The decision was a huge disappointment to advocates of a treatment that the FDA recognized as a "breakthrough therapy" in 2017—especially since the two Phase 3 trials, which were published by Nature Medicine in 2021 and 2023, had found that subjects who took MDMA fared substantially better than subjects who underwent the same psychotherapy but took a placebo. In the 2021 study, two-thirds of the MDMA group "no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD," compared to a third of the control group. In the 2023 study, more than 70 percent of the MDMA group no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, compared to 48 percent of the control group.

The FDA's decision nevertheless was unsurprising in light of an advisory panel's June 4 recommendation against approval. The committee, which included just one scientist with experience in psychedelic research, overwhelmingly concluded that MDMA's effectiveness had not been adequately established and that its benefits had not been shown to outweigh its risks. The FDA's concerns are rather puzzling, given that Lykos worked with the agency every step of the way to develop an acceptable research protocol.

The FDA declined to release the letter to Lykos in which it detailed those concerns, which it said is confidential. But the company's response suggests that the issues identified by the agency are similar to the ones highlighted by its advisers.

The company noted concerns that "Lykos' clinical data were insufficient to demonstrate durability." Lykos "believes that the data included in the NDA provide sufficient evidence of efficacy and durability in line with the relevant FDA guidance," the company said. "FDA's draft guidance for industry on psychedelic drugs indicates that endpoint data should be collected at 12 weeks; Lykos' Phase 3 studies collected endpoint data at 18 weeks, with additional exploratory endpoints collected six months or more later."

The advisory panel also raised "questions about expectancy bias stemming primarily from participants with prior MDMA use." The concern was that subjects whose previous experience with MDMA was positive would be primed to expect good results in the clinical trials, which might have skewed the results. But Lykos notes that it "aligned with the FDA" on "a variety of bias minimization measures in the study design" and that "prior MDMA use among participants was not previously viewed as detrimental." About 30 percent of the subjects in the company's Phase 2 trials reported prior MDMA use, a fact that "was shared with FDA before establishing the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the Phase 3 trial design."

In the two Phase 3 trials, Lykos noted, the data indicated that "prior illicit MDMA use had no impact on the results." There "was no meaningful difference in primary outcome measure…or adverse events reported between the subgroup of Phase 3 participants who reported prior illicit MDMA use and the subgroup of participants who did not."

The FDA's advisers also worried about "functional unblinding"—the likelihood that subjects surmised which group they were in based on the presence or absence of MDMA's distinctive psychoactive effects. "Functional unblinding is a known research challenge for psychiatric drugs with psychoactive effects," Lykos noted after the advisory committee's vote, and "it was discussed extensively with the FDA" during the development of the Phase 3 research protocol. "While there is no perfect solution to functional unblinding, we took many steps to minimize its potential impact, including the use of independent, blinded third-party clinician raters to assess outcomes," the company said. "The weight of evidence suggests a very low likelihood that the observed [MDMA] effect can be adequately explained by functional unblinding."

The advisory committee "also raised psychotherapy as a concern, with some recommending" that Lykos "further characterize the extent to which psychotherapy contributes to treatment benefit and if it is even necessary," the company noted on Friday. "Lykos acknowledges that [MDMA]-assisted therapy represents a novel combination of drug and therapy that raises unique research questions and will continue to engage the FDA as appropriate on these challenges."

In June, Lykos said "significant steps were taken to ensure standardization and consistency in the psychological intervention across therapists, sites, and treatment groups, and to thus allow for valid comparison between the [MDMA] and placebo groups." The success of those efforts, it said, "is supported by the lack of variability in treatment outcomes between Phase 3 clinical sites."

The FDA's advisers "raised questions regarding potential cardiovascular issues and hepatoxicity," Lykos noted in June. The company said that it "will continue to work with the FDA to characterize the data and/or collect new data to address these potential risks, if required," and that it is "confident that these can be safely addressed in a post-marketing environment."

As Lykos noted, issues such as prior MDMA use and functional unblinding were recognized all along, and the FDA previously did not view them as insurmountable barriers to approval. The psychotherapeutic component likewise was part of these studies from the beginning, and the FDA approved research protocols that included it.

In a Lykos press release, Jennifer Mitchell—a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who participated in the research—pointed out that developing the clinical trials was "an enormously complex undertaking" that the researchers tackled "over the course of many years…in consultation with the FDA and with an agreed Special Protocol Assessment in place." She called the FDA's decision "a major setback for the field."

Prior to the decision, bipartisan groups of senators and representatives wrote letters to the agency underlining the need for better PTSD treatments. "Existing treatments and medicines for PTSD, the last of which FDA approved nearly 25 years ago, have not decreased the frequency of suicide within the veteran community," Sens. Michael F. Bennet (D–Colo.), Rand Paul (R–Ky.), and 17 of their colleagues wrote. "As a nation, we cannot allow our veterans to continue to suffer in silence and must identify treatments proven to drastically decrease the adverse effects of PTSD."

Reps. Jack Bergman (R–Mich.), J. Luis Correa (D-Calif.), and 59 of their colleagues suggested that criticism of the Lykos research was misguided. "As this application has made its way through the regulatory review process, certain groups and individuals have voiced criticism of the application," they wrote. "It is our understanding that while these critics may be well-intentioned, their criticism is not necessarily reflective of the science, but rather their personal ideological beliefs and biases related to the medicalization of substances like MDMA."

Lykos is asking the FDA to reconsider its request for another Phase 3 trial, hoping that existing evidence will suffice to resolve the agency's concerns. "MAPS and our supporters have been advocating for the development and supporting the FDA-approved research of MDMA-assisted therapy for more than 38 years," MAPS founder Rick Doblin said in a press release. "MAPS will continue working towards safe, legal access to this therapy for the more than 350 million people living with PTSD worldwide."

MDMA would have been the first psychedelic approved as a medicine by the FDA. But ballot initiatives in Oregon and Colorado have legalized the use of psilocybin in psychotherapy. Taylor West, executive director of Oregon's Healing Advocacy Fund, suggests that state-level reform is a promising alternative in light of the FDA's decision, telling The New York Times that "the path to creating access to safe, psychedelic-assisted therapy is not going to run through Washington, D.C."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

If the FDA says it doesn't work, it must be great!

(maybe if more democrat congress-critters got some stock, it might get magically approved?

“Puritanism: The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” — H.L. Mencken

The FDA’s line on tests of new drugs seems to be, “Well, if we deny them long enough, everyone who suffers from the disease will die of old age, and we won’t have to worry about it.”

Using drugs that can seriously fuck with with your serotonin/dopaminergic system seems a terrible idea to treat people with PTSD caused depression. Might help, might not. There are plenty of reports of people having lasting mental detrimental effects from MDMA. Shrooms, on the other hand....

The research seems pretty promising. This isn't some new idea of just giving MDMA to PTSD patients and hoping something good happens. The proposed treatment isn't prescribing it to make them feel nice, it's used as an adjunct to psychotherapy to make it easier for people to remember traumatic events without panicking.

Want there some ultra test the CIA did on the same topic? Mmmkay

Hmm. Sort of, but with very different ends in mind.

Nice subtle pun there.

Yes some research seems promising. If it was compelling enough, the FDA would not have ruled as they did. From personal experience, MDMA fucked me up for a good year+. Took that long for my brain chemistry to re-balance. I am not alone. There are many (anecdotal) accounts on erowid.org. The problem with trying to gain legalization of psychedelics as medical adjuvents to therapy, is that they are massively powerful with unpredictable effects on a chemical level. As someone who has used, and been around psychedelics since grade school, I don't believe they are the panacea Joe Rogan thinks they are. Caveat Emptor.

If it was compelling enough, the FDA would not have ruled as they did.

I'm not convinced on that part.

And did your bad experience follow a single use, or were you partying it up for a while? Note that the proposed uses aren't to have people take it everyday, or even regularly, but to use it for therapy in a carefully controlled environment. Pretty much all drugs are dangerous (even the ones that aren't any fun). So the question isn't 'can this drug harm some people", of course it can. The question is whether it can do more good than harm to people who would stand to benefit from it. If you have severe PTSD and can't cope with life (and are likely already prone to excessive drug and alcohol use), then it seems like a small and worthwhile risk. It's always a cost/benefit analysis.

I would argue that you own your body and can choose to put whatever chemicals/drugs/plants into your body that you so desire. There shouldn’t be any laws against it. I’m a libertarian, and not a leftist, though, so I believe you are also responsible for the decisions you make. So you would be responsible for yourself if you fuck up your life by choosing poorly and deciding to binge MDMA repeatedly, for example.

All that being said, we don’t live in a society based on individual responsibility and self-ownership (Covid lockdowns and vax requirements, Selective Service obligations, prostitution laws, etc–to name some of the laws that violate self ownership). Under this flawed framework, I agree with what you wrote. MDMA (and some psychedelics) look promising in treating legitimate medical conditions and diseases. In fact, as I understand it, MDMA was first a therapeutic aid in treating PTSD going back as early as the late 70s to early 80s. As you said, it helped patients during therapy sessions confront the trauma they were bottling up. Therapists from back then said one to two sessions had the efficacy of a year of non-MDMA assisted sessions. There is no reason, other than politics and financial motivations, to have it as a Schedule I drug.

This decision at the FDA was likely not made purely for medical reasons. I agree with you on that.

I would argue that you own your body and can choose to put whatever chemicals/drugs/plants into your body that you so desire. There shouldn’t be any laws against it.

Totally agree. I don't believe using or making psychedelics should be criminal. Nobody should go to jail. The more difficult question is 'should corporations be able to mass produce and profit from peddaling such things?'.....which is exactly what will happen. If it happens, the government will be okay with it as long as they get a cut. Therapists will become de facto drug dealers. There will be a massive surge in PTSD cases. It's already happened with ketamine, adderall etc etc. I honestly don't give a shit what happens. Might help some people, might create more mental health/substance abuse problems than it solves.

shame FDA doesn't want world peace.

Besides voter initiatives and legislation, is anyone pursuing even the idea of state pharmacy boards licensing such treatments — or any treatments for anything, for that matter? Having state pharmacy boards decide such matters is usually bypassed in favor of FDA, although it was bandied about in the case of mifepristone.

^THIS. There was never an enumerated power for the 'Fed' to be doing this (Food and Drug) regulation.

Let's just say I'm skeptical of any drugs the government might want to give soldiers. I'm also skeptical of any drugs the government doesn't want to give soldiers.

I'd agree the research seems promising, but if memory serves MDMA floods the brain with serotonin and also last I checked there are other ways of achieving that effect that perhaps have lesser side effects. It seems pretty obvious that any drug that floods the brain with serotonin is probably going to have some effect on a mood disorder, which coincidentally is why a whole host of people with disorders self medicate with a wide variety of illegal narcotics...including MDMA.

Jesus, even Dan Crenshaw is in on this. Let's let people decide for themselves what they want to take and leave government out of it. Are we sovereign citizens or do we belong to The State?

This leads to a question I’ve long had: If the USA, or any country, had a libertarian enough president, would you want them to order FDA or the equivalent agency in their country to lie if necessary to say that all drugs, medical devices, food additives, etc. were safe and effective, as required by statute for their licensure? Or do you think too many people rely on getting an honest opinion from their government agencies as to the products in commerce in their respective country? If truth conflicted with liberty, would you side with truth or liberty?

I’d side with liberty and cynically declare all products safe and effective, and let people find the real answer without government help or hindrance. (This assumes that we didn’t have the horses to get legislation change, but only executive orders.) As in the movie of Bonfire of the Vanities, if the truth won't set you free, then lie. I've already done it as a juror in a federal narcotics case, and it felt really good! Lying to people in their face and knowing they know it but that there's nothing they can do about it is exhilarating.

Man, it's like they don't even like to party.

I thought you were cool, FDA. I thought you were cool.

Bet they don't even have any glowsticks.

Don’t get me started on the FDA, but if they won’t approve something, it’s likely that one of their better funded stakeholders doesn’t like it, or has another drug they don’t want competing with.