SCOTUS Ponders the Ambiguity of 'Ambiguous' and Other Chevron Doctrine Puzzles

The justices seem inclined to revise or ditch a 1984 precedent that requires deference to executive agencies' statutory interpretations.

Under a doctrine established in the 1984 case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, courts defer to a federal agency's "permissible" or "reasonable" interpretation of an "ambiguous" statute. As became clear during oral arguments in two Supreme Court cases challenging Chevron deference on Wednesday, that principle poses several puzzles, starting with the meaning of ambiguous.

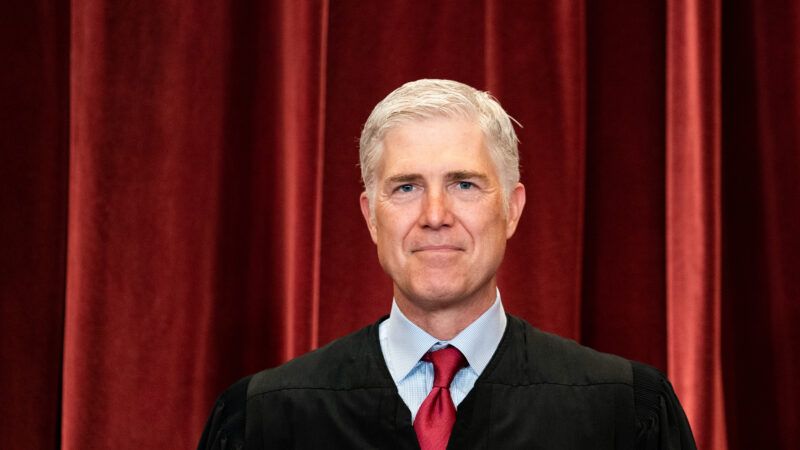

At least four justices—Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh—have criticized the doctrine for allowing bureaucrats to usurp a judicial function, and their skepticism was clear from the questions they posed to Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar. Only three justices—Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—were clearly inclined to stick with a rule that in practice empowers agencies to rewrite the law and invent their own authority.

The two cases, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce, both involve the question of whether herring fishermen can legally be forced to subsidize the salaries of on-board observers who monitor compliance with fishery regulations. The relevant statute explicitly authorizes the collection of such fees, within specified limits, from a few categories of fishing operations, but those categories do not include the New Jersey and Rhode Island businesses that filed these lawsuits.

Under Chevron, Prelogar argued, the National Marine Fisheries Service has the discretion to fill the "gap" left by congressional silence. The lawyers representing the plaintiffs, former Solicitor General Paul Clement and Washington, D.C., attorney Roman Martinez, argued that such deference violates due process, the separation of powers, and the rule of law by systematically favoring the executive branch's interpretation of any statute that might be viewed as "silent or ambiguous" on a point of contention between federal agencies and the people who have to deal with them.

"There is no justification for giving the tie to the government or conjuring agency

authority from silence," Clement said during his opening statement in Loper Bright. "Both the [Administrative Procedure Act] and constitutional avoidance principles call for de novo review, asking only what's the best reading of the statute. Asking, instead, 'is the statute ambiguous?' is fundamentally misguided. The whole point of statutory construction is to bring clarity, not to identify ambiguity." That approach, he added, is "unworkable" because "its critical threshold question of ambiguity is hopelessly ambiguous."

Gorsuch, who has been notably critical of the Chevron doctrine as a justice and an appeals court judge, and Kavanaugh, another critic of the precedent, zeroed in on that last point while questioning Prelogar during oral arguments in Relentless. "How would you define ambiguity?" Kavanaugh asked. "How would you, if you were a judge, say, 'yes, this is ambiguous' or 'no, that's not ambiguous'?"

Prelogar's response: "A statute is ambiguous when the court has exhausted the tools of interpretation and hasn't found a single right answer." She said judges should ask, "Did Congress resolve this one? Do I have confidence that actually I've got it, [that] I understand what Congress meant to say in this statute?" Applying that approach, she said, a court might conclude that "the right way to understand this statute is that it's conferring discretion on the agency to take a range of permissible approaches."

Kavanaugh asked Prelogar if she thought "it's possible for a judge to say, 'The best reading of the statute is X, but I think it is ambiguous, and, therefore, I'm going to defer to the agency, which has offered Y.'" When she said no, Kavanaugh was openly incredulous: "That can't happen? I think that happens all the time."

In response, Prelogar said "there are two different ways in which courts use the term 'best interpretation of the statute.'" A judge might "apply all of the tools" of statutory interpretation, as he is supposed to do under Step 1 of a Chevron analysis, and conclude that "Congress spoke to the issue." In that case, Prelogar said, even if "there's some doubt" about the correct reading of the law, a judge is not required to accept the agency's interpretation merely because it is "permissible." But if the judge decides "Congress hasn't spoken to the issue," she said, "filling the gap" is left to the agency's discretion, even if the judge "would have done it differently" as a matter of policy.

Gorsuch suggested that Prelogar had presented "two very different views" of a judge's function under Chevron. Under one approach, "there is a better interpretation," and the judge applies it. Under the other approach, the judge "defer[s] anyway given whatever considerations you want to throw into the ambiguity bucket." Some judges, he noted, "claim never to have found an ambiguity," while "other, equally excellent circuit judges have said they find them all the time."

Martinez noted that 6th Circuit Judge Raymond Kethledge falls into the first category, while the late D.C. Circuit Judge Laurence Silberman fell into the second. "If there's that much disagreement," Martinez said, "that's a sign that Chevron really isn't workable."

Prelogar suggested that the justices could respond to such widely varying understandings of ambiguity by reminding the lower courts that they are not supposed to give up on statutory interpretation just because it is difficult to choose between contending views. Gorsuch noted that the Supreme Court had delivered that message around "15 times over the last eight or 10 years," telling judges they should "really, really, really go look at all the statutory [interpretation] tools." Yet even in "this rather prosaic case," he said, one appeals court "found ambiguity," while the other arguably "tried to resolve it at Step 1," which suggests judges "can't figure out what Chevron means."

In short, while Prelogar argued that Chevron promotes uniformity by constraining judges from reading their own policy preferences into the law, Gorsuch et al. argued that it has the opposite effect. As Gorsuch put it in 2022, "all this ambiguity about ambiguity" has allowed courts to apply what Kavanaugh described, in a 2016 law review article, as "wildly different conceptions of whether a particular statute is clear or ambiguous."

Sotomayor noted that she and her colleagues frequently disagree about how best to interpret a statute, leading to narrowly decided cases that come down on one side or the other. "If the Court can disagree reasonably and come to that tie-breaker point," she asked Martinez, "why shouldn't deference be given" to an agency with "expertise," experience with "on-the-ground execution," and "knowledge of consequences"? That account of what Chevron requires, Martinez replied, implies that a statute is "ambiguous because reasonable people can disagree" about its meaning, which confirms that the doctrine assigns a judicial function to executive agencies.

Prelogar also argued that preserving Chevron would promote "stability" and "predictability," noting that both legislators and regulators have come to rely on the assumption that agencies have broad discretion in filling gaps and resolving ambiguity. Overturning Chevron, she said, would be an "unwarranted shock to the legal system." But Gorsuch et al. argued that Chevron actually has undermined stability by allowing agencies to overrule judicial interpretations and "flip-flop" between different readings of a statute, depending on the agenda of any given administration.

The "best example" of the latter, Clement told the justices, is the question of whether broadband internet companies are offering a "telecommunications service" or an "information service," which has a crucial impact on the regulatory authority of the Federal Communications Commission. Gorsuch brought up the same example, noting that the Supreme Court had deferred to the Bush administration's view of the matter, saying "you automatically win." But then the Obama administration "came back and proposed an opposite rule," which the Trump administration reversed. And "as I understand it," Gorsuch added, the Biden administration "is thinking about going back to where we started."

Big businesses, Gorsuch noted, have the resources to keep up with such shifting statutory interpretations and influence the process, which can result in "regulatory capture," since "there's a lot of movement from industry in and out of those agencies." In Chevron itself, the Supreme Court deferred to an agency interpretation that benefited regulated companies. "I don't worry…about those people," Gorsuch said. "They can take care of themselves."

Gorsuch contrasted that situation with "cases I saw routinely" as a 10th Circuit judge, which involved "the immigrant, the veteran seeking his benefits, the Social Security disability applicant." Those supplicants, he noted, "have no power to influence the agencies" and "will never capture them," and their interests "are not the sorts of things on which people vote, generally speaking." Gorsuch said he had yet to see a case "where Chevron wound up benefiting those kinds of people." He said it therefore looks like the Chevron doctrine has a "disparate impact on different classes of persons." In other words, the doctrine tends to screw over the little guy—an argument that Gorsuch said was "powerfully" raised by the plaintiffs in Relentless and Loper Bright, who complain that the contested regulatory fees amount to about a fifth of the revenue earned by their family-owned businesses.

Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson, by contrast, amplified Prelogar's argument that agency experts are best situated to fill in the gaps left by Congress when it passes legislation. Kagan suggested that judges are not qualified to resolve issues such as whether "a new product designed to promote healthy cholesterol levels" should be treated as a strictly regulated "drug" or a lightly regulated "dietary supplement." She also cited regulation of artificial intelligence as an area where Congress might reasonably choose to let agencies decide the details. Given the rapid and unpredictable pace of A.I. developments, she said, "there are going to be all kinds of places where, although there's not an explicit delegation, Congress has in effect left a gap" or "created an ambiguity."

Jackson likewise said she viewed Chevron as "helping courts stay away from

policy making." If the decision were overruled, she worried, "the Court will then

suddenly become a policy maker by majority rule or not, making policy determinations."

Both sides agreed that Congress can explicitly give agencies broad leeway—for example, by authorizing "reasonable" or "appropriate" regulations. But they disagreed about what should happen when Congress is silent. In that situation, "the delegation is fictional," Martinez argued. "There's no reason to think that Congress intends every ambiguity in every agency statute to give agencies an ongoing power to interpret and reinterpret federal law in ways that override its best meaning."

Gorsuch raised the same objection. "You've said that it doesn't matter whether Congress actually thought about it," he told Prelogar. "There are many instances where Congress didn't think about it. And in every one of those, Chevron is exploited against the individual and in favor of the government."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Of course, it is faintly possible that the founding fathers meant for all restrictions on citizens to result solely from legislation passed by congress and signed by the president.

Just a thought based on a scrap of parchment I read once.

The primary objective of the justice system, SCOTUS, is to operate in an environment of “ the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth”.

They have criminalized perjury to do so. The rest of civilized society has similarly tried to minimize the harm caused by lying by criminalizing fraud.

The effort to support truth has been successfully opposed by the full spectrum of corruption in society, from presidents and crime bosses to cheating spouses.

The easiest way to identify truth is to eliminate the ambiguity surrounding any issue. For example, abortion is killing an innocent human being, something we all recognize as murder regardless of the victims age.

Criminalize lying resulting in the codification in law what constitutes proof of truth.

Update the constitution to declare our inalienable right to record all our memories that we want to everywhere we go to defend ourselves against liars and prosecute criminals.

Good, that would be one of the best things the court could do.

Not overly excited about this. Mostly begging the question and rearranging deck chairs. Let me know when the argument is whether the Feds should be regulating any of this in the first place.

It would certainly eliminate more regulation, or at least allow it to be challenged, than anything Trump did or could do.

Trump’s appointees are the reason why Chevron is being considered. Your TDS is showing.

Goalposts go whoosh. I was obviously talking about the claims that he took an axe to the federal register. You know, all the talk of Trump The Great Deregulator before this case came to the court.

I do agree that he picked some good justices.

"Goalposts go whoosh."

You do this on purpose, right?

Says something retarded then pretends he didn't say it? Yes. He does.

Full retard achieved. The media has dozens of stories about the dangers of trumps deregulation.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks-list.html

https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/washington-secrets/trump-slashing-regulations-boosted-economy-more-than-tax-cuts

You really are a leftist fuck at this point lol.

More...

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-trump-administrations-major-environmental-deregulations/

And. .

https://www.forbes.com/sites/waynecrews/2018/10/23/trump-exceeds-one-in-two-out-goals-on-cutting-regulations-but-it-may-be-getting-tougher/

I mean I can go on and on dumdum.

So what? I'm saying that if this case is ruled correctly, that vast swathes of regulation could be in the cross hairs. This doctrine has been in effect since the 80s. That's a lot of time for writing rules based upon silence from Congress.

Much more than Trump ever repealed.

And whatever Trump repealed your guy reinstated.

So what? Youre assertion was wrong and based on ignorance. So you… moved goal posts. And terribly.

Regulationd won't magically disappear by ending Chevron retard. It will be a long winding set of cases from the courts with leftist judges ignoring the ruling. See gun control post Heller retard.

That's not TDS, it's just recognition of the limited power of the executive.

Yes, it is Trump's Federalist Society appointees, who want to kill most of the federal govt (except the military, that they love) are doing this. TDS is a result of being deranged from the insanity of a con artist leading the country. This will kill ALL regulation. Gonna be great when poor people start starving, roads can't be built, retirees can't get SS or Medicare. But, no barriers to building those mansions on wetlands now...

You do realize that Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are Trump appointees to the Court?

Don’t confuse him with facts.

I think y’all are being a little unfair. He did say “could do”, clearly referencing the fact that the President only wields so much power to cut regulations.

Yeah, it would open up a lot more avenues to removing regulations. It's ridiculous that executive agencies get the presumption that their readings of the law are valid.

But they disagreed about what should happen when Congress is silent.

I don't know how anyone can honestly argue that silence from Congress means bureaucrats can just make stuff up.

Because FYTW?

Gorsuch and Kavanagh are definitely sniffing in the right direction here. The Supreme Court may be worth their salaries, (on average) after all.

Hopefully they overturn Chevron and go for Wickard next.

>>The justices seem inclined to revise or ditch a 1984 precedent that requires deference to executive agencies' statutory interpretations.

the Rehnquist court should have been equally if not more so inclined.

Only one of the failures of the Rehnquist court.

the list is long and distinguished.

Gorsuch is barking up the wrong tree in commenting on whether Chevron hurts the little guy. That’s irrelevant. What’s relevant is whether Chevron is constitutional. He’s making the same kind of argument progressives usually make: whether it’s “good” policy, rather than lawful.

If The Supremes followed the Constitution, the executive branch would never have been delegated this much authority in the first place. They just throw us a bone once in a while. In this case it's a pretty big bone.

Well, remember that oral arguments are sometimes used to feel out and even influence other justices. I think Gorsuch understands that constitutionality should be the only relevant question but Kagan, Sotomayor and Jackson clearly disagree. Gorsuch's "little guy" comment was probably designed to appeal to them.

Consider that part of the Constitution is the idea that laws are applied equally. Thus if a law is hurting one group while another benefits from it, it is therefore unconstitutional. Bringing up the fact that the laws and interpretation of them under Chevron hurts one group but benefits another is actually holding to the constitutional question.

I completely agree with you. Look what the CDC,FDA and DEA have done to legitimate chronic pain patients with their "broad interpretation " of laws.

Um what? People who steal are disproportionately affected by criminal laws. Or an example from non-culpable conduct, people who fly are disproportionately affected by TSA laws, and those who fly internationally are disproportionately affected by passport/migration laws.

"Affecting one group more than another" has jack shit to do with constitutionality. EVERY law does that.

Tell me you don't understand the concept of 'disparate impact' without telling me you don't understand the concept of 'disparate impact.'

Further, he isn't making the same argument, just pointing out that the current interpretation violates the long held tradition that laws have to be equally applied. This actually predates the Constitution. These are questions that date back to Anglo-Saxon English law and has been at the root of all major events in the formation of English Common Law and subsequently US common law. It was actually one of the major reasons behind the American Revolution, that as English Citizens, the colonists deserved equal protection and rights under the law, specifically the right to have representation in Parliament before being taxed and regulated.

Depends on the audience for his statements. Setting the court's Leftist justices squarely as oppressors of minorities and the people as well as stooges of corporate interests could limit their dissent if not flip their votes if they don't win (7-2 is more authoritative than 5-4). If his opinion is of that frame and not equal protection or flat out constitutionality then there is more reason to be pissed/object.

I think Gorsuch is invoking equity (as a legal concept, and specifically in the Aristotelian sense, not what social justice warriors have abused the word to mean). That's also a valid concern of a court, especially when the doctrine itself is court-invented.

As I said before, ambiguous laws should be struck down as unconstitutional! On the other hand, the argument here is whether a particular law is ambiguous. There are two possible ways that a law could come to the attention of a judge as ambiguous: the first would be when a regulatory agency "interprets" the law to give it the authority to regulate when the law did not explicitly give it that authority; and the second way would be when the wording of the law itself was unclear as to what was covered or what the authority of the agency covered. The second example is easy to lead to a ruling striking the law down completely. If Congress failed to word the law in such a way that almost anyone with or without legal training could interpret, the last thing we should want would be for a bureaucrat to create a new meaning. The first example would represent an abuse by the regulator and would not necessarily require that the whole law be struck down. In that case the judge should simply strike down the abuse by the regulator as outside the scope of their authority!

Most cases of the second type are like the example Kagan gave, wherein the statute's language left it unclear whether a certain thing or activity were of type A, which Congress gave an agency authority to regulate that way, or of type B, which Congress gave the same or another agency authority to regulate this way. I don't think the inclarity entitles the judge to strike down the entire provision so it won't be regulated as either type A or B.

Or consider the big undefined term in the Controlled Substances Act, "abuse". I could see that part being ruled void for vagueness, so that any article controlled solely on the basis of its administratively-determined "abuse" would be decontrolled, but I don't think you could void the whole control schedule, including substances named statutorily.

The case law on that last one really reveals a lot of heavy stuff hanging by a very thin and long thread that presumes Congress must've meant something, so the judges referenced a since-repealed statute that had mostly the same language, whose legislative history included a committee report that used the term in a certain way to make it possible for a certain Democratic candidate for governor of California to look tough on crime by cracking down on uppers and downers, which in turn referenced an agency report, which rested on some recently-invented medical jargon...I can't remember the whole to-do, but it basically means you can't argue the facts because the definition predetermines the outcome and is beyond the reach of anyone outside officialdom.

"Overturning Chevron, she said, would be an "unwarranted shock to the legal system.""

That whole Justice though the heavens may fall thing is so old and outdated?

God forbid we would ever shock any officials feeding at the public trough. It might ruin their whole day!

We are dealing with two levels of scum when it comes to malicious manipulation of language and concepts like "ambiguous": lawyers and Leftists. There is no redefinition or feigned ignorance (real as well) they will not deploy to get to their desired outcome.

That is correct.

Thank god for Trump. We'd be so much farther down the Bolshevik road without the justices he appointed. Incredible what a difference it makes really.

Only three justices—Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—were clearly inclined to stick with a rule that in practice empowers agencies to rewrite the law and invent their own authority.

The diversity hires? No. Say it isn’t so.

Next thing you know we’ll be pointing out that retarded blind midgets aren’t the best choice for flying airplanes.

So.... It turns out Ketanji Brown Jackson is all for bureaucrats usurping knee-jerk legislative powers ... As well as the rest of the justices elected by Democrats.

Never-mind considering the US Constitutional authority of these bureaucrats now even when whim law (leader dictation) is on the table some can't even uphold that restriction for the people.

If the law is silent or ambiguous about something then the government has no enforcement authority unless and until congress passes the law and the executive signs it

I wonder why Kagen, Sotomayor, and Brown hate the “little guy” all the while pretending to be all for them?

Because they’re racist?

Are we sure Brown even knows who the "little guy" is? She's not a metrologist you know.

The "little guy" just needs to shut up and do as they are told; per progressive values, that is what is best for them/us.

The principle underlying the doctrine of Stare Decisis actually requires reversing, not merely overturning, Cevron deference.

Stare Decisis, aka let the decision stand, is base on the premise that the purpose of law is NOT punishing offenders. It is encouraging compliance. In order to comply with laws, one must be able to determine what actions comply with and what actions fail to comply with the law. That requires consistency in the law. If the court rules one day that the law requires and/or permits X, and later rules the opposite, people can't determine if a given action complies with the law. Therefore, once a court has interpreted a law to mean Y, the courts should continue to interpret the law to mean Y until the law is changed.

Based on that premise, the law should ALWAYS be interpreted in favor of the defendant when there is legitimate ambiguity. In short, the government agency should ALWAYS bear the burden of proving their interpretation.

Overturning Chevron is a start, but it would be far better to go back to Constitutional principles and require Congress to do its job. Neither agencies nor courts should resolve true ambiguities. Such laws should be void for vagueness, sending them back to Congress. Until Congress acts, courts and agencies should universally decide in favor of individuals and against the government.

Neither are bureaucrats. Is there an option C? That people together with their doctors decide what’s appropriate to take for their heart. Whether it’s a judge or a career suit, neither have any business making those sorts of arbitrary choices.