The DOJ Says Marijuana Use, Which Biden Thinks Should Not Be a Crime, Nullifies the Second Amendment

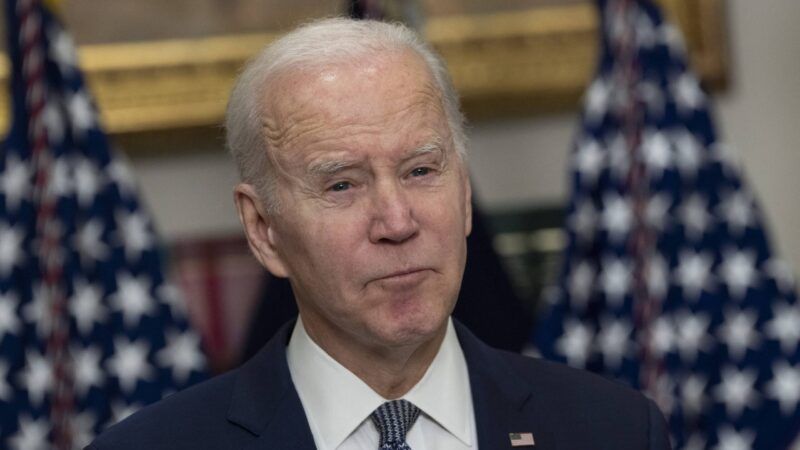

Even as the president bemoans the injustice of pot prohibition, his administration insists that cannabis consumers have no right to arms.

President Joe Biden thinks it is unfair that people convicted of simple marijuana possession face lingering consequences for doing something that he says should not be treated as a crime. Biden cited those burdens last October, when he announced a mass pardon of low-level federal marijuana offenders, which he said would help "thousands of people who were previously convicted of simple possession" and "who may be denied employment, housing, or educational opportunities as a result." Yet the Biden administration, which recently began accepting applications for pardon certificates aimed at ameliorating those consequences after dragging its feet for five months, is actively defending another blatantly unjust disability associated with cannabis consumption: the loss of Second Amendment rights.

Under federal law, it is a felony, punishable by up to 15 years in prison, for an "unlawful user" of a "controlled substance" to possess firearms. The ban applies to all cannabis consumers, even if they live in one of the 37 states that have legalized medical or recreational use. That disability, a federal judge in Oklahoma ruled last month, is not "consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation"—the constitutional test established by the Supreme Court's 2022 decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. The Justice Department recently filed a notice indicating that it intends to appeal the decision against the gun ban for marijuana users.

The Biden administration's defense of the ban relies on empirically and historically dubious assertions about the sort of people who deserve to exercise the constitutional right to keep and bear arms. Among other things, the Justice Department argues that "the people" covered by the Second Amendment do not include Americans who break the law, no matter how trivial the offense. It also argues that marijuana users are ipso facto untrustworthy and unvirtuous, which it says makes them ineligible for gun rights.

According to the Biden administration, the original understanding of the right to arms included exceptions broad enough to encompass people who consume any intoxicant that legislators might one day decide to prohibit. It says the law criminalizing gun possession by cannabis consumers is analogous to laws targeting "intoxicated" people who carry guns in public places.

Judge Allen Winsor, whom Donald Trump appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida in 2019, accepted that last argument in November. Winsor dismissed a lawsuit in which Nikki Fried, a Democrat who was then Florida's commissioner of agriculture and consumer affairs, argued that medical marijuana patients have a constitutional right to own guns. Winsor agreed with the Biden administration that they do not.

By way of historical precedent, Winsor noted colonial and state laws enacted in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries that prohibited people from either carrying or firing guns "while intoxicated." The analogy was strained, since those laws, which applied only when people were under the influence, did not apply in private settings and did not categorically prohibit drinkers from owning guns. Although Fried's Republican successor declined to appeal Winsor's decision, the patients who joined the lawsuit are asking the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit to review their case.

Another Trump appointee, Judge Patrick Wyrick of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, disagreed with Winsor in response to a challenge brought by a dispensary employee who was charged with violating the federal ban on gun possession by marijuana users. In a February 3 ruling, Wyrick said the government had failed to meet the Bruen test.

In trying to do so, Wyrick noted, the Justice Department had cited "ignominious historical restrictions" that disarmed slaves, Catholics, loyalists, and Native Americans. He rejected the government's argument that such precedents showed it was constitutional to withhold Second Amendment rights from any group that legislators deem "untrustworthy."

Wyrick was similarly unimpressed by the Biden administration's claim that the Second Amendment includes a "vague 'virtue' requirement.'" That theory, he said, is "belied by the historical record" and "inconsistent" with District of Columbia v. Heller, the landmark 2008 decision in which the Supreme Court explicitly recognized that the amendment guarantees an individual right to keep firearms for self-defense.

Although simple marijuana possession is a misdemeanor, the Justice Department argued that illegal drug use frequently entails felonious conduct even when a drug user has not been convicted of a felony. Wyrick was dismayed by the government's claim that any violation of the law that legislators classify as a felony is enough to justify the nullification of someone's Second Amendment rights.

"History and tradition support disarming persons who have demonstrated their dangerousness through past violent, forceful, or threatening conduct," Wyrick wrote. "There is no historical tradition of disarming a person solely based on that person having engaged in felonious conduct."

Such a policy, Wyrick warned, would be an open-ended license to deprive people of their Second Amendment rights. "A legislature could circumvent the Second Amendment by deeming every crime, no matter how minor, a felony, so as to deprive as many of its citizens of their right to possess a firearm as possible," he wrote. "Imagine a world where the State of New York, to end-run the adverse judgment it received in Bruen, could make mowing one's lawn a felony so that it could then strip all its newly deemed 'felons' of their right to possess a firearm."

Wyrick posed that very hypothetical to the government's lawyers. "Remarkably," he said, "when presented with this lawn-mowing hypothetical argument, and asked if such an approach would be consistent with the Second Amendment, the United States said 'yes.' So, in the federal government's view, a state or the federal government could deem anything at all a felony and then strip those convicted of that felony—no matter how innocuous the conduct—of their fundamental right to possess a firearm."

Florida's Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, also rejects the Biden administration's position. "The governor stands for protecting Floridians' constitutional rights—including 2nd Amendment rights," his office said after Fried filed her lawsuit. "Floridians should not be deprived of a constitutional right for using a medication lawfully."

The National Rifle Association (NRA), which for years declined to challenge the rule that Fried argued was unconstitutional, now goes even further than DeSantis. Amy Hunter, the NRA's director of media relations, recently told me "it would be unjust for the federal government to punish or deprive a person of a constitutional right for using a substance their state government has, as a matter of public policy, legalized."

This controversy is part of a broader debate about the constitutionality of criminalizing gun possession by broad categories of "prohibited persons." In addition to "unlawful" drug users, those categories include anyone who was ever subjected to involuntary psychiatric treatment, whether or not he was deemed a threat to others and regardless of his current mental health, and anyone convicted of a crime punishable by more than a year of incarceration, whether or not it involved violence and no matter how long ago it occurred.

Critics of the latter rule, including Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett and 3rd Circuit Judge Stephanos Bibas, argue that it is broader than the Second Amendment allows. The relevant history indicates that "legislatures have the power to prohibit dangerous people from possessing guns," Barrett wrote in a 2019 dissent as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit. "But that power extends only to people who are dangerous."

The ongoing litigation over the gun ban for cannabis consumers means that two appeals courts, the 11th Circuit and the 10th Circuit, will have a chance to weigh in on the question.* Appeals courts, including the 7th Circuit and the 9th Circuit, previously have deferred to the congressional assertion of a drug exception to the Second Amendment based on hand-waving references to an association between drug use and violence. But those decisions were issued before Bruen established a more demanding constitutional test for gun control laws. That historical test explicitly rules out "any judge-empowering 'interest-balancing inquiry' that 'asks whether the statute burdens a protected interest in a way or to an extent that is out of proportion to the statute's salutary effects upon other important governmental interests.'"

Whatever the appeals courts ultimately decide, it is more than a little odd that the Biden administration says marijuana use is not serious enough to justify criminal penalties or the practical difficulties that a conviction entails yet somehow is serious enough to nullify a constitutional guarantee. That contradiction is a measure of how committed Biden is to a vision of Second Amendment rights that makes them contingent on legislative whims.

*Correction: This original version of this post misidentified the federal circuit that includes Oklahoma.

Show Comments (57)