Germany's Criminalization of Online Offensiveness Shows the Perils of Weakening the First Amendment

A crackdown on insults, hate speech, and misinformation punishes dissenters who express themselves in ways that offend government officials.

Americans who are alarmed by online "hate speech" and "misinformation" tend to resent the limits that the First Amendment imposes on government intervention against objectionable content. But German authorities do not suffer from such constraints, and the consequences should give pause to critics who are sympathetic to the idea that freedom of speech sweeps too broadly in the United States. As a New York Times story published today shows, the ongoing German crackdown on "hate speech, insults and misinformation" has predictably subjected political dissenters to police investigation and criminal penalties for expressing their views in ways that offend the powers that be.

The article begins by describing a case involving an apocryphal quote attributed to Green Party politician Margarete Bause. "Just because someone rapes, robs or is a serious criminal," Bause supposedly said, "is not a reason for deportation."

After an unnamed 51-year-old man shared that "fake remark" on Facebook, police visited his home, which they searched for half an hour, seizing a laptop and tablet as evidence. He now faces a fine equivalent to about $1,400. Even if he did not realize the comment was bogus, prosecutors said, "the accused bears the risk of spreading a false quote without checking it."

That penalty, Bause tells the Times, was "a warning shot that they can't just accuse and hurt people with impunity." Svenja Meininghaus, a prosecutor who participated in the case, concurs. "There has to be a line you cannot cross," he says. "There has to be consequences."

The raid on the Facebook user's home was one of about 100 conducted on the same day last March, "part of a coordinated nationwide crackdown that continues to this day." As police and prosecutors see it, they are deterring potentially lethal speech. Their crusade was partly inspired by a neo-Nazi's June 2019 assassination of Walter Lübcke, a local politician who "became a regular target of online abuse after a 2015 video of him had circulated in far-right circles." In that video, Lübcke "suggested to a local audience that anyone who did not support taking in refugees could leave Germany themselves."

Violence of any kind, let alone murder, is obviously an intolerable response to speech. But the German government has taken the further step of deeming speech that might inspire violence intolerable. Since criminal laws are ultimately enforced at the point of a gun, the government has thereby authorized violence in response to speech—the very evil it supposedly is fighting.

In the United States, concerns about violence can justify restrictions on speech only in narrowly defined circumstances, such as "true threats" and intentional incitement of imminent lawlessness. Another, potentially broader exception, for "fighting words," originally applied to "words that by their very utterance inflict injury" and "speech that incites an immediate breach of the peace." After announcing that doctrine in 1942, the Supreme Court repeatedly narrowed it, to the point that many critics think it is no longer a viable rationale for upholding a criminal conviction.

In Germany, speech protections are substantially weaker. The government has long treated Holocaust denial and the display of Nazi imagery as crimes, for example, and it prohibits "incitement to hatred" more generally. It is also a crime to insult someone publicly or engage in "malicious gossip."

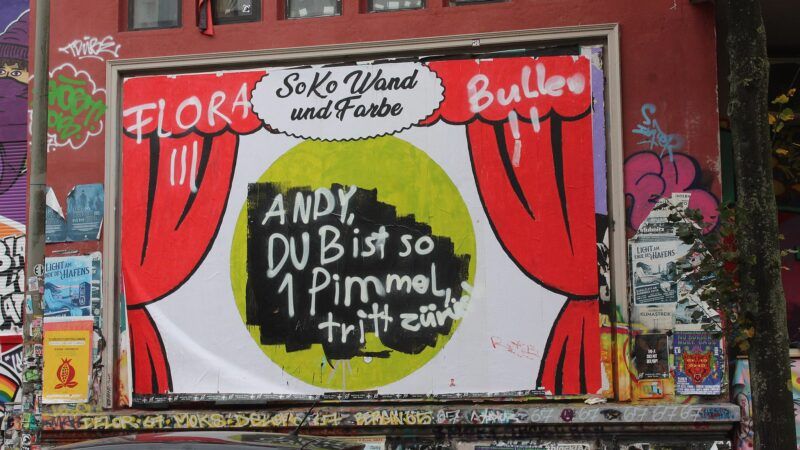

The latitude that such laws grant was vividly illustrated last year by a case involving a Twitter user who insulted Andy Grote, a Hamburg official who had violated the pandemic-inspired social distancing rules he was charged with enforcing by "hosting a small election party in a downtown bar." After Grote tweeted about the need for responsible behavior to avoid a return to lockdowns, the critic replied: "du bist so 1 Pimmel"—"you are such a dick."

Three months later, that succinct retort prompted an early-morning police raid, which in turn provoked a backlash that came to be known as Pimmelgate. "Activists printed stickers of the Twitter remark and plastered them around Hamburg, forcing the police to clean them up," the Times notes. "Then activists painted a mural with the phrase, forcing the police to paint it over more than once."

The case "raised concerns that illegal speech was too vaguely defined and gave local prosecutors and the police too much discretion about enforcement." As if to prove that point, police subsequently raided the home of Alexander Mai, an Augsburg climate activist who got into a Facebook argument with "a local far-right politician named Andreas Jurca." Mai's crime: He responded to a Jurca message "criticizing Muslims" by posting a link to a photo of the "du bist so 1 Pimmel" mural.

Mai suspects that "the raid was politically motivated because of his climate activism." However well-grounded that suspicion might be, the breadth of Germany's speech restrictions is an invitation to abuse by any cop or prosecutor with a political or personal grudge. And contrary to what progressives who rail against "hate speech" and "misinformation" might expect, the victims are not necessarily wrong-thinking people promoting retrograde ideas.

In addition to battling messages they think might inspire violence or hatred, German officials claim to be promoting freedom of speech by making online forums friendlier. Josephine Ballon, legal director at HateAid, a Berlin organization that "provides legal aid for victims of online abuse," thinks that makes sense. Because of trolling and ad hominem attacks, she tells the Times, "people withdraw from debate more and more and don't dare to express their political opinion."

But what happens when the government investigates and punishes people for remarks that it considers insulting, hateful, or misinformed? Unlike "online abuse," those efforts are backed by legally authorized force, which is apt to have an even stronger chilling effect.

"You can't prosecute everyone," a former Justice Ministry official tells the Times, "but it will have a big effect if you show that prosecution is possible." That is precisely the problem.

Show Comments (68)