Cops Arrested Her for Exercising Her First Amendment Rights. They Got Qualified Immunity—but the Appeals Court Wasn't Having It.

"This is not just an obvious constitutional infringement—it's hard to imagine a more textbook violation of the First Amendment."

Whether you can exercise your First Amendment rights freely depends, in some cases, on where you live and what judges happen to hear your plea, should you try to seek accountability for government reprisal against your civil liberties.

One such case is that of Priscilla Villarreal, a journalist in Laredo, Texas, who in 2017 was arrested after publishing two stories that ruffled feathers in the community: one surrounding a U.S. Border Patrol agent who committed suicide, the other which confirmed the identity of a family who had died in a fatal car crash.

Villarreal was no stranger to breaking stories with sensitive details on her Facebook page, which currently boasts over 190,000 followers. Nor was she cozy with local law enforcement, having cultivated a reputation as a citizen journalist who focuses on police misconduct and the justice system in videos she posts online infused with colorful commentary. She once live-streamed a video of an officer choking someone during a traffic stop, for example, and she drew the ire of a district attorney after publicly rebuking him for dropping an arrest warrant for someone accused of animal abuse.

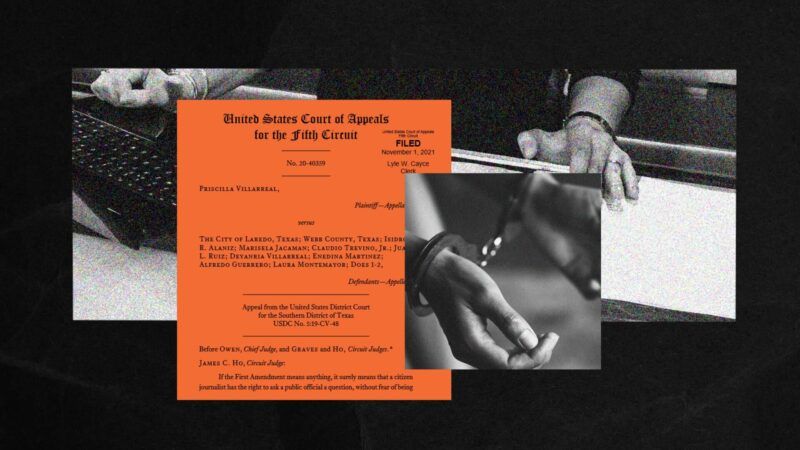

But Villarreal found herself in a jail cell after breaking those two relatively benign stories concerning deaths in the community, charged with two third-degree felony counts of "misuse of official information" under Texas Penal Code § 39.06(c). That she asked for and obtained the information in typical journalistic fashion—from the Laredo Police Department (LPD) itself—didn't matter to the cops, who zeroed in on Villarreal as the first person they would ever seek to prosecute under that Texas statute.

The charges were eventually dismissed as baseless and the law ruled unconstitutionally vague. But those officers were given qualified immunity for violating her First Amendment, Fourth Amendment, and 14th Amendment rights when they arrested and detained her, thus preventing her from holding them accountable in civil court. The legal doctrine of qualified immunity protects public officials from facing civil suits if the precise way they went about violating your rights was not "clearly established" by the courts at the time.

Yet in a testament to the subjectivity of the decisions surrounding what should be objective liberties, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit Monday rejected the lower court's reasoning, removing qualified immunity from the cops on the bulk of Villarreal's claims and permitting her to state her case before a jury.

"This is not just an obvious constitutional infringement—it's hard to imagine a more textbook violation of the First Amendment," wrote Judge James C. Ho. "If the freedom of speech secured by the First Amendment includes the right to curse at a public official, then it surely includes the right to politely ask that official a few questions as well." Villarreal asked those questions of LPD Officer Barbara Goodman, who of her own free will provided the journalist with the information she requested.

The 5th Circuit likewise sided with Villarreal on her wrongful arrest claim, as well as her allegation that the cops violated the Equal Protection Clause to selectively enforce the law against her.

Much about the decision is noteworthy. Ho, for one, is by no means known for his opposition to qualified immunity; the judge previously said that police officers must retain the protections in order "to stop mass shootings." So it's significant that Ho emphasized that the 5th Circuit need not find a nearly indistinguishable precedent in order to show that the constitutional right at issue was "clearly established"—which is often the defining element of a qualified immunity case, and the reason why the doctrine has greenlit so much egregious government misconduct, like stealing, assault, and property damage.

To support his position, Ho cited the Supreme Court's 2020 decision in Taylor v. Riojas, which dealt with a group of prison guards who originally received qualified immunity after forcing a naked inmate into two deplorable cells swarming with human feces and raw sewage. The Supreme Court overturned that grant of qualified immunity and rejected the notion that the victim could not sue simply because he couldn't pinpoint a ruling that matched his experience almost identically.

That's not necessary here either, said Ho: The constitutional violation is just that absurdly apparent.

"Crucially, the decision also says that officers can't hide behind obviously unconstitutional statutes," says Jaba Tsitsuashvili, an attorney at the Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm that filed an amicus brief in support of Villarreal. "In other words…'we were just enforcing the law' is not a categorical defense against a civil lawsuit for violating" a constitutional right.

Perhaps ironically, the 5th Circuit's decision Monday coincided with the Supreme Court declining to hear Frasier v. Evans, a case in which a group of Denver police officers received qualified immunity after conducting a warrantless search of a man's tablet in an attempt to delete a video he took of the officers beating a suspect during an arrest for an alleged drug deal.

Put more bluntly, the way you exercise your First Amendment rights may or may not be protected based solely on where you live and which federal circuit court you are subject to. The 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, and 11th Circuits have all confirmed what might be obvious to most: that the government cannot exact revenge on you for filming police on duty, a lever used to hold them to account. In some places, however, they can indeed retaliate and evade accountability for that, too—just as Villarreal almost missed her opportunity to do so, had the 5th Circuit not overturned the lower court's decision.

"It creates this territorially arbitrary vindication of rights, where if you're in one state you may be able to vindicate a constitutional right," says Tsitsuashvili, "but if you happen to be in a neighboring state that sits in a different judicial circuit, you won't have any recourse for essentially the exact same behavior."

Show Comments (32)