Supreme Court Declines To Hear Louisiana's Defense of a Law That Stamped 'SEX OFFENDER' on Driver's Licenses

The policy imposed an additional form of ritual humiliation on a reviled category of people without any plausible public-safety justification.

The U.S. Supreme Court today declined to hear Louisiana's appeal of a decision against its 2006 law requiring that people on the state's sex offender registry carry IDs or driver's licenses that say "SEX OFFENDER" in orange capital letters. A year ago, the Louisiana Supreme Court concluded that the requirement amounted to compelled speech and could not be justified by the state's legitimate interest in protecting public safety. In addition to raising First Amendment issues, Louisiana's now-moribund law illustrates the longstanding tendency to impose additional punishment on people convicted of sex offenses in the guise of regulation.

The registries themselves, which require sex offenders to regularly report their addresses to local law enforcement agencies so that information can be made publicly available in online databases that also include their names, photographs, and physical descriptions, are primarily punitive, exposing registrants to ostracism, harassment, and violence while impeding their rehabilitation by making it difficult to find employment and housing. There is little evidence that the sort of public notification practiced by every state delivers benefits that outweigh those costs. Louisiana's experiment in ritual humiliation, which branded registrants with orange letters they had to display in every transaction that required producing a government-issued ID, compounded those costs without offering any plausible benefits.

One problem with sex offender registries is that they cover a wide range of crimes, including many that do not involve violence, force, or physical contact. While people tend to imagine rapists or child molesters when they hear the term sex offender, the reality can be quite different, in ways that are important in assessing the danger that a person might pose to the general public or to people in particular age groups.

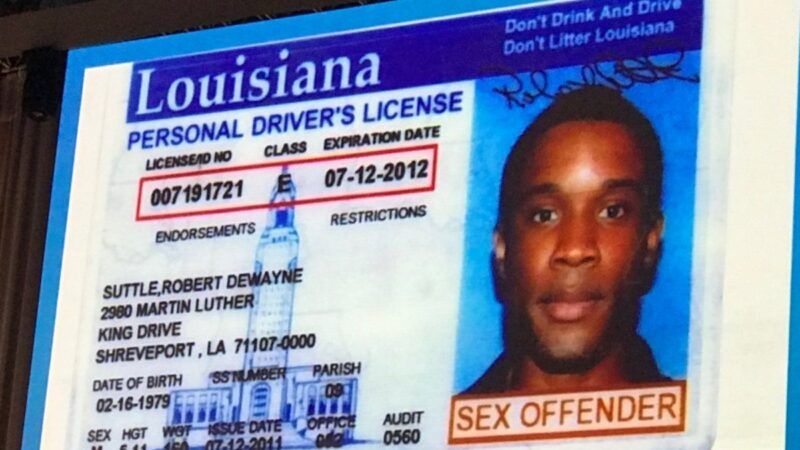

In Louisiana, for example, mandatory registration applies not only to crimes like rape and sexual assault but also to nonviolent offenses, such as voyeurism, possession of child pornography, consensual sex between adults who are closely related, sex between high school teachers and students (even when the student has reached the age of consent), and employment of a minor in "any practice, exhibition, or place, dangerous or injurious to the life, limbs, health, or morals of the minor." Robert Suttle, who posted the picture of his driver's license shown above, was forced to register because he was convicted of intentionally exposing someone to HIV, which resulted in a six-month prison sentence. After a bad breakup, he says, his former partner told the police he had not been informed of Suttle's HIV status.

The second line of each record in the state's registry shows the offender's "tier," which corresponds to various crimes classified by severity, ranging from Tier 1 (least serious, requiring registration for 15 years) to Tier 3 (most serious, requiring lifetime registration). Further down in the record, you can see the statute under which the registrant was convicted (e.g., "carnal knowledge of a juvenile"), which still omits potentially important details.

The driver's license warning required by Louisiana's law did not provide even that much information, meaning that anyone who saw it was invited to assume the worst. Tazin Hill, the man who challenged the law, completed his prison sentence in 2013. He was convicted of having sex with a 14-year-old when he was 32, which placed him in Tier 1. But anyone who saw his license had no way of knowing the nature or severity of his offense. Rebelling at this government-imposed badge of shame, Hill excised the "SEX OFFENDER" label from his license and covered the gap with clear tape, which resulted in the criminal charges that gave rise to this case.

Another problem with sex offender registries is the mistaken assumption that people who fall into this broad category are more likely to commit additional crimes than, say, robbers, burglars, or arsonists. When it upheld mandatory "treatment" of sex offenders in prison, for example, the Supreme Court relied on a highly dubious recidivism estimate that was repudiated by its original source but has nevertheless been cited repeatedly by lower courts. The "SEX OFFENDER" stamp on Louisiana driver's licenses, even more than the registry, promoted such erroneous fears by implying that the bearer posed an ongoing threat, no matter the details of his crime, how long ago it occurred, or how he had behaved since he completed his sentence.

The empirically unjustified belief that sex offenders are highly prone to recidivism is especially inaccurate and damaging when applied to people convicted as minors, who are included in Louisiana's registry and therefore had to carry "SEX OFFENDER" IDs or driver's licenses. Judy Mantin, who this year testified before a state legislative committee that was considering revisions to Louisiana's law in light of the state Supreme Court's ruling, said her son "made a mistake" when he was 14 but today is "a very productive citizen." She argued that "our children deserve a second chance in life."

Legislators ostensibly have made the same judgment regarding adults convicted of sex offenses, who have notionally paid their debt to society once they complete their criminal sentences. Yet legislators imply otherwise by imposing additional burdens on those people for decades after their official punishment. In this case, any interaction involving a driver's license—e.g., with cashiers, hotel clerks, bank tellers, employers, landlords, election officials, or airport security screeners—became a new invitation to close-range fear and loathing.

What was the justification for this requirement, which added to the burdens imposed by registration, public notification, and residence restrictions? The state argued that the "SEX OFFENDER" label facilitated law enforcement by alerting police officers to a person's status. But police already could readily check that by consulting the state's database. And as the Louisiana Supreme Court noted, the state could have eliminated even that slight inconvenience with a more discreet label: "A symbol, code, or a letter designation would inform law enforcement that they are dealing with a sex offender and thereby reduce the unnecessary disclosure to others during everyday tasks."

Such a solution would not be adequate, the state argued in its petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, because "the Louisiana Legislature concluded that the public, and not merely law enforcement, needs to know of a sex offender's status under limited circumstances." Such as?

"A property manager needs to know a sex offender's status when leasing an apartment—or the manager might incur liability if a tenant is raped on the premises," the petition said. "A church or Red Cross facility may need to know a person's status as a sex offender when providing shelter from a storm. People trick or-treating on Halloween may need a quick way to verify that their children are safe from predators."

During a lower-court hearing, one of the state's lawyers offered another example:

If I'm deciding who I want to be my babysitter and I know that I don't want a sex offender to babysit my children, I say, "OK. I'd like to see your ID before I allow you to babysit my children." And, "Oh, it says 'sex offender.' I'm not going to hire you."

The Halloween scenario suggests the state's desperation, not only because this particular hazard is an urban legend but also because it is difficult to imagine a situation in which parents would demand to see the driver's licenses of neighbors handing out candy to trick-or-treaters. Even when the concerns are more reasonable, the public registry, for better or worse, already allowed anyone to look up an individual and see if he was listed; that was supposedly the whole purpose of creating a publicly accessible database in the first place.

"Louisiana's branded-identification regime was an outlier in singling registrants out for public opprobrium," Hill's lawyers noted in their brief urging the Supreme Court not to consider the state's appeal. "Just two other States require identification cards to display phrases like 'SEX OFFENDER,' while only six States have laws that require identification cards to include other types of sexual offense disclosure—typically a symbol or statute number recognizable only to law enforcement."

Even as an outlier, Louisiana's law suggests how ready politicians are to support practically any burden on sex offenders, whether or not it makes sense as a tool to promote public safety. Policies like these serve no useful purpose, but they do make life harder for a reviled category of people whose punishment never ends.

Show Comments (96)