Do Sex Offender Registration Laws Do Any Good?

The Detroit Free Press takes a skeptical look at a system that treats public urinators like predators.

Last month a federal judge ruled that certain aspects of Michigan's Sex Offenders Registration Act (SORA) are unconstitutionally vague. Sex offenders, for example, are forbidden to live, work, or "loiter" within 1,000 feet of "school property." U.S. District Judge Robert Cleland noted that such "school safety zones" are not clearly defined, making it difficult to comply with the law. He said the term loiter is vague as well: Does it apply, say, to people attending their children's parent-teacher conferences or their grandchildren's school plays? Cleland said two other rules—requiring registrants to report all email addresses they "routinely used" and all vehicles they "regularly operated"—presented similar compliance challenges. "SORA was not enacted to serve as a trap for individuals who have committed sex offenses," he wrote. "Rather, the goal is public safety, and public safety would only be enhanced by the government ensuring that registrants are aware of their obligations."

In a follow-up story published yesterday, the Detroit Free Press casts doubt on that public safety rationale. "While [laws like SORA] may have helped parents rest easier," writes reporter L.L. Brasier, "there is no evidence that they stopped sexual predators." There was never much reason to think they would, especially since the vast majority of sexual assaults on minors are committed by people without prior convictions who know their victims well, as opposed to strangers who might be flagged by an online database.

Meanwhile, the burdens imposed by registration requirements, which include a stigma that poisons relationships and ruins job prospects, could make recidivism more likely. "These laws destroy what's valuable about someone's freedom," University of Michigan law professor J.J. Prescott tells Brasier. "You're a pariah virtually everywhere, you can't live in most neighborhoods, and nobody wants to date, marry, or socialize with you. You can't find a job because no one will hire a sex offender….These laws take away their reasons for staying on the straight and narrow, for working hard to become a valuable member of a community."

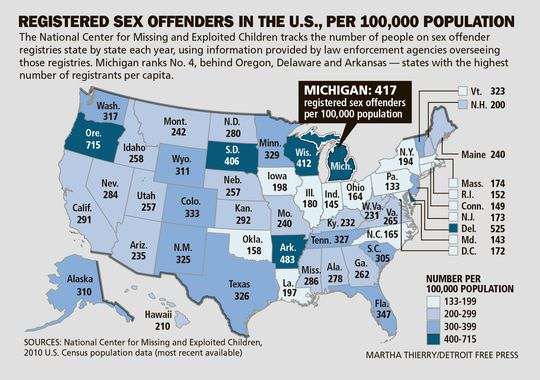

The case for registration is especially weak when states make little effort to distinguish between low- and high-risk offenders. As Brasier notes, the overall recidivism rate for sex offenders is much lower than commonly believed. Yet Michigan's registration system classifies offenders based purely on the crime of conviction, without regard to other factors that make recidivism more or less likely. Worse, it includes minor, nonviolent offenders such as public urinators and teenagers who have consensual sex with younger girlfriends. Offenders must continue to register for periods ranging from 15 years to life even if their records are expunged. Michigan's wide net is reflected in the fact that it has more registered sex offenders per capita than all but three other states (Oregon, Arkansas, and Delaware).

Brasier cites several examples of sex offenders who are forced to register even though they do not pose a threat to the general public, including a Florida couple arrested for having sex on a public beach and a Michigan man convicted of having sex with the woman who is now his wife. As long as states mix such offenders in with predatory criminals, it is hard to take their claims of protecting public safety seriously.

I highlighted the problems with registration requirements and other policies aimed at sex offenders in a 2011 Reason feature story. More from Reason TV:

Show Comments (35)