A Houston Man Framed on Drug Charges Is Suing the Lethally Corrupt Cop Who Sent Him to Prison

Otis Mallet's ordeal, like the deaths of Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas, involved a fictional drug purchase.

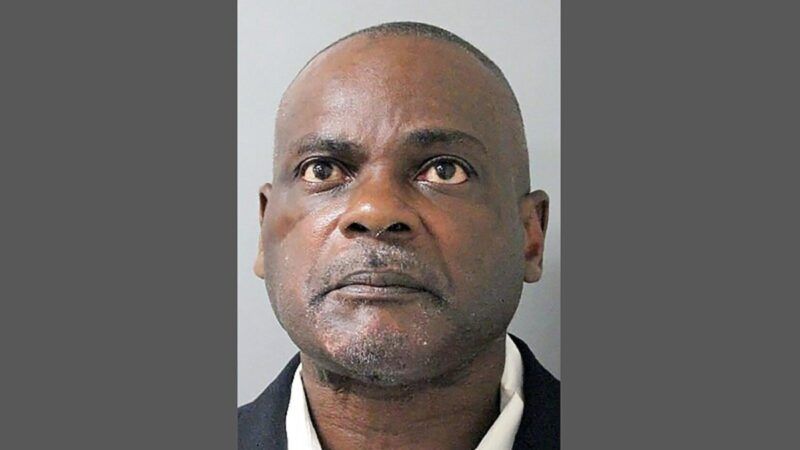

Ten years ago, Otis Mallet was convicted of selling crack cocaine in Houston based on a transaction that prosecutors and state courts eventually concluded never happened. But in the meantime, Mallet was sentenced to eight years in prison, of which he served two before he was released on parole. This travesty might never have come to light but for the scrutiny that followed a deadly 2019 drug raid orchestrated by Gerald Goines, the same narcotics officer who framed Mallet. That operation, which killed a middle-aged couple, Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas, whom Goines portrayed as heroin dealers, was likewise based on a fictional drug purchase.

In a federal lawsuit filed last week, Mallet is seeking compensatory and punitive damages from Goines and his immediate supervisor, Sgt. Troy Gamble, for violating his constitutional rights. He argues that Goines knowingly framed him and that Gamble would have discovered that fact if he had been doing his job properly. The details of the case belie former Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo's assurances that the disastrous 2019 raid did not reflect a "systemic" problem in his department. They also show how the war on drugs facilitates outrageous police abuses that would be more easily discovered in other kinds of criminal cases.

According to a police report that Goines filed, he was working undercover on April 29, 2008, when he drove an unmarked car to 1121 Danube Street. Goines supposedly gave Mallet's brother, Steven, $200 in cash, which he gave to Otis, who retrieved a blue can from a black Chevrolet truck parked at the house, removed crack from it, and handed it to Otis, who delivered it to Goines. As he drove away, Goines said, he notified his colleagues, who arrested the two brothers.

Goines' testimony was the only evidence against Otis and Steven Mallet. There were no other witnesses to the alleged transaction, and the can that he claimed contained the crack he supposedly bought had no usable fingerprints. Neighbors said they had not seen anything like the transaction Goines described. A drug-sniffing dog did not alert to the truck where Mallet allegedly had stashed the can of crack. During Otis Mallet's trial, the prosecution said that, given his many years of public service, Goines "deserves to be treated with more respect than he's been treated with."

After the raid that killed Tuttle and Nicholas, local prosecutors began reexamining drug cases involving Goines, a 34-year veteran who had worked in the Houston Police Department's Narcotics Division for two decades. During a February 2020 hearing in which prosecutors urged a judge to recommend that Otis Mallet be declared "actually innocent," they said Goines "repeatedly lied about nearly every aspect" of the case. Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg said Goines' refusal to testify at Mallet's hearing was "compelling evidence that the entire alleged narcotics transaction was a fraud."

Harris County District Court Judge Ramona Franklin agreed that Mallet should be declared innocent, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed that finding. "No credible evidence existed that inculpated [the] defendant," it said, "and the defendant [was] actually innocent of the crime for which [he] was sentenced." Mallet later received $260,417 in state compensation for his wrongful conviction.

Another Harris County judge, Kelli Johnson, reached the same conclusion regarding Steven Mallet, who pleaded guilty to possession in exchange for a sentence of time served—10 months. He said he had rejected an earlier plea deal that would have required him to implicate his brother and decided to plead guilty only so he could get out of jail. The appeals court agreed that he was innocent.

Although Otis Mallet had always maintained his innocence, his claims got no traction until after investigators discovered that Goines had invented a heroin purchase by a nonexistent confidential informant to justify the home invasion in which his colleagues killed Tuttle and Nicholas. Goines faces state charges, including felony murder, and federal civil rights charges in connection with that raid.

Mallet argues that Goines' supervisors should have been aware of his chicanery long before it had deadly results. His lawsuit notes that nine complaints against Goines were sustained between 1987 and 2005, including allegations of "misconduct" and "improper police behavior." And although Goines claimed he had used "police money" to buy crack from Mallet, that money was never recovered, and it was not mentioned in Goines' expense report for April 2008. The following month, Goines said he had paid a confidential informant $200 for assistance in identifying the Mallet brothers as drug dealers, a detail that is conspicuously missing from his description of the crack purchase in his report and other case documents.

Since Gamble signed off on Goines' paperwork and was supposed to be supervising him, the lawsuit argues, he is culpable in Mallet's false arrest. "As Defendant Gamble was present as a surveillance officer for Plaintiff's arrest in April of 2008," the complaint says, he "was aware" either that Goines "was not accounting for drug buy money associated with Plaintiff's arrest" or that Goines "did not actually use any drug buy money in connection with Plaintiff's arrest." If Gamble "had been properly supervising Defendant Goines," the lawsuit argues, "this red flag would have caused the investigation into Plaintiff to be more thoroughly reviewed, the fact that a drug buy did not occur would have been discovered, and the malicious prosecution against Plaintiff would have been terminated prior to his wrongful conviction."

In a 2020 interview with the Houston Chronicle, Gamble said he did not recall the Mallet case, but he implicitly agreed that the inconsistencies between Goines' paperwork and his account of what had happened should have prompted scrutiny. Gamble "said he reviewed any expenses on any case he was involved with—and a situation where expense reports didn't line up with details in an arrest report would concern him." He emphasized that "all the expenditures should add up" and that "if you spend money, any money spent should be documented."

This sloppiness is of a piece with the lax supervision and outright fraud that Ogg's investigators discovered in the Narcotics Division. "Houston Police narcotics officers falsified documentation about drug payments to confidential informants with the support of supervisors," Ogg said in July 2020. "Goines and others could never have preyed on our community the way they did without the participation of their supervisors; every check and balance in place to stop this type of behavior was circumvented." Ogg's findings resulted in criminal charges against a dozen officers, including several supervisors, who are accused of falsifying reports to back up drug cases and claim phony overtime.

Acevedo and his underlings are clearly responsible for allowing this corruption, even when they were not actively participating in it. In a federal lawsuit against the city of Houston, Acevedo, and 13 current or former officers, the Nicholas family says the narcotics squad to which Goines belonged "operated as a criminal organization and tormented Houston residents for years by depriving [them of] their rights to privacy, dignity, and safety."

Drug law enforcement is especially conducive to the egregious misconduct that sent Otis Mallet to prison before it killed Tuttle and Nicholas. By criminalizing peaceful transactions between consenting adults, drug prohibition creates opportunities for Goines-style fakery that would not otherwise exist.

When someone is murdered, there is a body. When someone is assaulted, there are injuries. When someone is robbed, there is stolen property. In all of those cases, there are identifiable victims, and there may also be independent witnesses who are motivated to come forward because they have an interest in punishing and deterring predatory crime. But when a "crime" consists of nothing but handing a police officer or an informant something in exchange for money, the evidence often consists of nothing but that purported buyer's word, along with drugs that easily could have been obtained through other means.

Leaving aside the blatant injustice of punishing people for conduct that violates no one's rights, this situation invites dishonest cops to invent drug offenses and take credit for the resulting arrests, as Goines did for years with impunity. When your job is creating crimes by arranging illegal drug sales, it is not such a big leap to create crimes out of whole cloth, especially if you are convinced that your target actually is a drug dealer. This line of work also offers many opportunities for other kinds of police corruption, such as stealing drugs or drug money and taking bribes to look the other way.

Acevedo, meanwhile, has decamped for Miami, where he is running that city's police department. Miami Mayor Francis Suarez called him "the best chief in America."

The fraudulent raid that killed Tuttle and Nicholas did not dim Acevedo's enthusiasm for the war on drugs. He repeatedly praised the officers involved in that operation, including Goines, as "heroes" while tarring their victims as dangerous drug dealers and claiming that neighbors were grateful that his officers had eliminated a locally notorious "drug house." Even after it became clear that the operation was built on lies from start to finish, Acevedo concluded that the problem was a few bad apples, as opposed to the rotten barrel built by drug prohibition and supervisory negligence. Now he is Miami's problem.

Show Comments (42)