Lance Armstrong vs. the New Honor Code

Should Americans be tougher on our celebrities—and ourselves? A leading anthropologist says yes.

Do people who have acted horribly in public life deserve a second chance, or does giving them a pass contribute to a decline in morality and standards that makes us all worse off?

I'm not talking about the extreme and obvious cases, like movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, who was sentenced to 23 years in prison on rape and assault convictions. And I'm not talking about people getting fired or pushed out of jobs because of random dumb posts, woke mobs, or years-old statements ripped out of context.

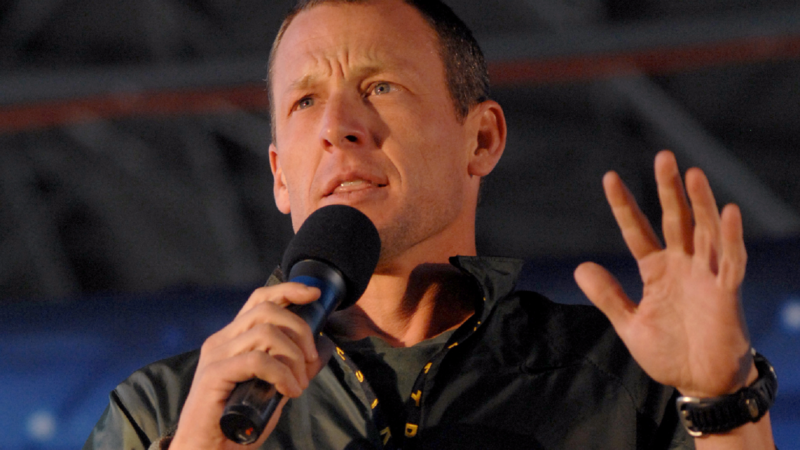

I'm talking more about public figures such as Lance Armstrong, who was stripped of his record seven Tour de France titles in 2012 after getting caught using banned substances for basically his entire professional career and lying about it. Should we let him and others like him back into the public spotlight when they don't really own their mistakes or try to repair the damage they've done to public trust and confidence? Overall, I think we're generally too quick to let bygones be bygones, with the predictable result that our trust in each other and our institutions is tanking.

Armstrong is working his way back into the spotlight after making a few public apologies that didn't really convince anyone. Last year, he was the subject of an ESPN documentary and he's currently the face of WEDŪ, an events and media company where he hosts a podcast that covered the 2019 Tour de France and raked in an estimated $1 million in revenue during the month-long event.

Cultural anthropologist and brand consultant Grant McCracken is a hard no on Armstrong. "Here's a guy who doped, who insisted that he didn't dope, and accused his competitors of doping," says McCracken, who has taught at Harvard and MIT and worked with Netflix, Google, and Kanye West. "We are open-hearted Americans, we like to think that all people should be forgiven. People make mistakes. It's always the second act in American culture. I'm not sure there should be a second act. I think once you've done something as bad as that you're done, you're out."

His new book is The New Honor Code: A Simple Plan for Raising Our Standards and Restoring Our Good Names and I interviewed him at length for a podcast (listen here). Honor, or the expectation that we'll hold ourselves and others to high standards, has gone missing in too much of our lives, he argues. We often let celebrities and public figures get away with what he calls monstrous behavior partly because we view them as entertainment and partly because we project ourselves onto them and don't want to judge ourselves too harshly. In his book, he points out that even some Armstrong critics argued that virtually everyone in cycling used performance-enhancing drugs and some defenders of Weinstein minimized his assaults by pointing to the long history of Hollywood's casting couch.

Lowering our standards and explaining away bad people by claiming that everyone breaks the rules leads to lower and lower standards for our own personal behavior in turn. In a system where everyone cheats and gets away with misdeeds, McCracken says, only a fool actually plays by the rules, especially when no one is looking.

McCracken is no moral scold and he doesn't always call for the figurative equivalent of the death penalty for malefactors. But he says too often people don't seem to pay any serious price for bad behavior. He writes about the 2016 scandal involving the Harvard men's soccer team, some of whom created a spreadsheet ranking the sexual desirability of members of the women's team in graphic detail and then violating the school's honor code by lying about it when it was first discovered. The players involved got away with publishing an unsigned apology in the student paper and Harvard's then-president and dean of students also let it all slide. "When you look at the details and you don't look at the damage done by this behavior—there's a detailed account of how one young woman reacted psychologically—it's horrifying," says McCracken. "These guys regard themselves as above reproach, suggesting that some larger point has to be made here. They have to understand what they did and the cost of what they did."

McCracken is the first to admit that there isn't a clearly objective measure of whether we're less honorable than we were 25 or 50 years ago, but I think he's fundamentally right that we tolerate a huge amount of absolutely rotten behavior that should be called out for what it is. If our response to lying, cheating, and acting despicably is simply a collective shrug, we can't be surprised when we get more of the same.

How might we restore honor to our culture? McCracken says that a positive honor culture—one which expects individuals to uphold standards of behavior even when they conflict with personal desire or gain—still exists in the military. He acknowledges that bad behavior still exists in the armed forces but says it's rarely excused on the grounds that everyone does it. "Nobody in the military ever says, 'Well, everybody goes AWOL, or everybody steals stuff, or misuses their power,'" he says. "I think you get more good behavior when there is bad behavior that's more culpable, that's more punishable."

McCracken believes that we must also do more to recognize and celebrate the people in our community who do all sorts of things that make our lives better. He writes about Bob, his neighbor in a small town in Connecticut, who has quietly helped build Little League fields, volunteers at local hospitals, and is active in his church. "This guy does all this stuff," says McCracken. "He's completely unheralded. Nobody in my community has any clue of what he does. I thought, we need more Bobs. There are about five Bobs in my community. If you created a reputation economy and you found some way of giving people credit for these accomplishments, you might be able to inspire 30 Bobs to behave in this manner. And all boats would rise with that tide."

We live in an era where trust and confidence in government, business, and religious and charitable institutions are at or near historic lows and continue to decline. The past year's experiences with police, politics, pandemics, and riots aren't going to turn that trend around anytime soon. While endless—and often insane—examples of cancel culture make it clear that none of us wants to live in a world of one strike and you're out, we'd do well as a society to think seriously about McCracken's call for a new honor code.

We'll always be adjudicating what we consider bad behavior and the appropriate social response on a case-by-case basis, but it's time to hold public figures and ourselves accountable for making the world a better place.

Watch "Is American Too Forgiving? The Case of Lance Armstrong":

Show Comments (87)