The EU's New Privacy Rules Are Already Causing International Headaches

It's not just email spam; GDPR has led companies to shut down access to sites and games.

Well, that didn't take long. The European Union's long-awaited (and commercially dreaded) privacy regulations, known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), have already begun wreaking havoc online.

Before the rules took effect on May 25, commentators had warned that the GDPR would consolidate power in the hands of market titans while confusing businesses about what exactly the regulations require. Indeed, early signs show that Facebook and Google, despite the threat of fines, are the big regulatory market winners. And EU bureaucrats themselves don't seem to know what "compliance" really looks like.

But the GDPR has caused chaos in more unexpected ways also. Here are just a few of the head-scratching unintended consequences that the GDPR has wrought across the globe.

Email-a-palooza: Most people's familiarity with the GDPR begins and ends with the avalanche of consent emails they received in the weeks before the regulations took hold. Services that you may not have heard from for years were suddenly quite eager to extol their "updated privacy policies" and cajole you for your approval.

For some of us, this was good opportunity to de-list ourselves from long-forgotten apps and web sites with which we'd sooner not share our data. But for a lot of people, it was merely another exercise in clicking "agree" without reading a word of the fine print. This doesn't do a lot for improving data privacy, but it might protect some services from hefty GDPR fines.

Or not. Ironically, companies that sent out GDPR emails on good faith to ensure compliance may have ended up actually violating the GDPR. In a Kafkaesque kind of Eurocratic catch-22, some EU watchers argue that a company that lacks the consent for their current data practices could also lack the consent to email people to gain their consent. Have a headache yet? This is just one small sliver of the GDPR red tape nightmare.

Another irony unfolds in how consent practices have largely ended up helping the tech titans that EU regulators wished to rein in. A household name like Facebook or Google will have a much easier time getting consent from users than an unknown competing platform or ad vendor. The big guys effortlessly check the box, but the upstarts get lost among the piles of consent emails—all for nothing.

The Google Data Protection Regulation: While we're on the subject of Google, the publishing industry has taken to calling the GDPR the "Google Data Protection Regulation" for its market consolidating effect. Google already dominates the ad market, accounting for some 44% of online advertising revenues in 2017 (Facebook snags another 18%). In the EU, Google accounted for 50% of all ad spends before the GDPR. The first day after the rules took effect, Google vacuumed up an astounding 95% of EU ad money.

Google benefits in second-order ways as well. Any policies that Google sets for its vendors yields dramatic impacts. Ad tech vendors have reported dramatic drops in business following the GDPR, and Google had limited the number of approved vendors that can participate on its platform until recently. If the EU wanted to tame Google's online dominance, they have a funny way of showing it!

Now you see it, now EU don't: The GDPR is long and complicated. It is so dry and ambiguous and monotonous that a meditation app called "Calm" offers a soothing bedtime reading of the 88-page regulation to help the listener "lie back, wind down, and drift off to the sound of a new legal regulation."

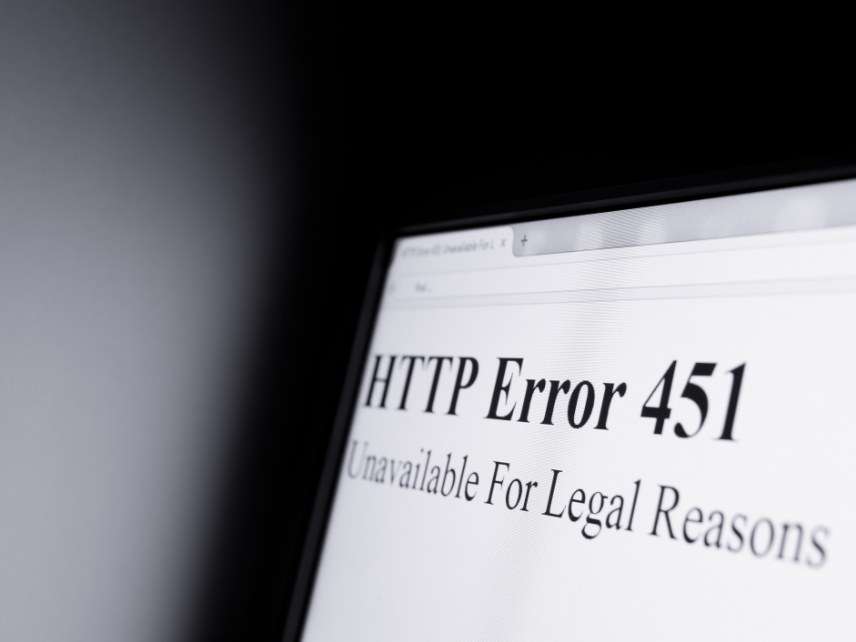

Not everyone has the time to read and internalize such a dry and complicated document. Some U.S.-based websites and services opted to put off dealing with the GDPR altogether.

Instapaper, a bookmarking service owned by Pinterest, announced on May 24 that it would be unavailable to EU members because of GDPR uncertainty, adding that it intended to "restore access as soon as possible."

News-minded EU citizens found themselves locked out of American media platforms on the day that the GDPR took effect. European fans of the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and other Tronc- and Lee Enterprises-owned news services were greeted with a message that the websites were unavailable until the publishers found a way to deal with GDPR compliance. A&E Networks, which includes A&E, Lifetime, and the History Channel, simply decided to pull down their websites from EU access. Needless to say, this cut off European audiences from significant sources of American news, all because some random regulator decided it was not in their best interest to access it.

Others took a segregating approach. The Gannett-owned USA Today directing those with an EU IP address to a stripped-down platform known as "the EU experience." NPR similarly directed readers who opted out of its cookie and tracking policy to a text-only website. The Washington Post charges for its version of a GDPR-compliant subscription package, which costs 50 percent more than a normal subscription.

Who knows? Maybe some platforms will decide that dealing with European users just isn't worth the hassle. EU citizens will have their own regulators to thank.

It's about data in gaming: Will gamers rise up against the GDPR? Some gaming platforms have been forced to close servers or shut down altogether over costs wrought by the EU regulations.

Some of the affected games include Loadout, Super Monday Night Combat, and Ragnarok Online. The CEO of Loadout, Rob Cohen, was pretty blunt in an interview with Motherboard about the changes: "There is a pretty lengthy list of changes required by GDPR. We'd have to update our client, server, database, and more. It's a pretty big amount of development work for a game that is no longer in development." Loadout fans enjoyed their last sad gaming session on May 24, the day before the rules took effect.

The situation was similar for Super Monday Night Combat, another online game. This long-running platform has struggled to keep its servers up in the past. Add in the major regulatory liability of the GDPR, and you've got a basically unworkable situation. SMNC's CEO Jeremy Ables told Engadget that they just couldn't afford to make the changes that the GDPR required. So the game shuttered its doors instead. Ragnarok Online, on the other hand, decided to simply shut off access to EU players. Only time will tell if this evasive maneuver is enough to keep the potential €20 million in GDPR fines at bay.

Supporters of the GDPR will argue that platforms that cannot comply with the GDPR simply do not deserve to stay in business. "Well, what kind of data shenanigans were they up to, then?" is their smug reply to news of the small ventures that the GDPR forces to go under. But it's hard to argue that indie gaming ventures that operate as passion projects for their small legion of dedicated gamers really constitute the biggest data problems facing society. Many of these are simply small projects which barely have the resources to keep their servers online without the pressure of millions in potential EU fines. But to the interventionist-minded, the death of indie games are a small price to pay for the achievement of a new regulatory tool.

Hey, Twitter! Leave those kids alone! The EU apparently feels like it has some kind of parental authority over its youths. The GDPR is heavy on rules surrounding data consent, and it draws an arbitrary line that a person must be 13 years old to give full consent. This rule is problematic enough on its own, but because of the vague way that the regulations are written, it is causing online platforms to react in odd ways.

Exhibit A is Twitter's retroactive banning of users who they believe signed up when they were 13 or younger. Many of these users are well over the age of 13, with some of them in their early twenties. But depending on how the EU decides to interpret its rules, any content that was generated by anyone under the age of 13 could be illegal, even if that person is now a legal adult. To be safe, Twitter has apparently been deleting the content of anyone they believe was under the arbitrary limit when it was posted.

This has inadvertently caught random companies and brands in the snare of Twitter's wide net, who listed the "birthday" of the account as the day that the company was founded. It's annoying, and a little nonsensical, but this is the kind of contortions that online platforms are pushed to in a post-GDPR world.

"Knock, knock." "WHOIS there?" "Um, not anymore.": Journalists, security professionals, and amateur internet sleuths alike rely on a protocol called WHOIS to investigate websites to determine provenance and registration data. Many free WHOIS services display the contact information for individuals and entities that set up websites so that the public can discern, well, "who is" behind specific web addresses.

Obviously, much of this information would be radioactive under the GDPR, so internet infrastructure services have had to scramble to determine how they will handle WHOIS services in the new regulatory environment. ICANN, the international organization that manages top level domain registrations, is dealing with the law by redacting important parts of WHOIS lookups, at least for the time being. While services existed in the past to redact WHOIS information for free or a fee, these changes would compel such censorship largely across the board.

As commentators have pointed out, this change bodes poorly for the future of cybersecurity research and investigations, which rely on WHOIS data to track the source of scams and attacks. And journalists and citizens alike will now lack one more tool to sniff out the sources of propaganda campaigns and other hijinks.

And this is just a snapshot of the world that the GDPR has created. Some of the effects have been odd and irritating, others will have dramatic negative effects on the dynamism and security of the global internet infrastructure. It's hard to tell exactly what the end impact of the GDPR will be on the overall landscape of the internet, but you can bet on one thing: the EU bureaucrats who shaped these policies will almost certainly never admit what they did wrong.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Fuck the GDPR. Back from Argentina. Terrorizing the populace with fear.

Have we learned nothing from history?

Euro Wars: Return of the Stasi.

Yes. We've learned to carefully control and craft the bits of history we teach.

It's almost as if those who control the past control the future.

Well said.

Given how much of an impact just losing WHOIS support will have on online security and the ability for the internet to inter-operate, a strong case can be made for simply cutting the EU off from the rest of the internet.

a strong case can be made for simply cutting the EU off from the rest of the internet.

Maybe France can provide Minatel to the rest of the continent.

Or, hell, maybe China will let them use their intranet.

Thank god Reason is always here to stick up for the interests of the poor downtrodden left-wing tech billionaire. Truly the forgotten minority.

Those are the people who are benefiting most from GDPR and Reason is criticizing it. If you can't be arsed to read the article why are you arse enough to comment on it?

If you can't be arsed to read the article why are you arse enough to comment on it?

REEDING IZ 4 FAGGITS N CUCKZ!

I work at nurse resume writing service and I recognize showcasing work history around the resume that shines might be a struggle, as they are expressing your need to get recent results for a completely new company in the resume resume cover letter. I merely recently got hired inside a job, additionally to received numerous interview offers from previous applications and am attempting to help others stick out due to a correctly organized resume with greater writing.

Mm, I ned to make sure to go on Google, and see if I can strip them off anyway to make money off me.

In a Kafkaesque kind of Eurocratic catch-22, some EU watchers argue that a company that lacks the consent for their current data practices could also lack the consent to email people to gain their consent.

Good Lord. This is absurd. People sending me letters in the mail don't need my consent first. Same with email.

Gosh - I'm like shocked man.

Call Central Committee!!!

"NPR similarly directed readers who opted out of its cookie and tracking policy to a text-only website."

Please please please tell me it had a shitty font with tacky color on a tacky background and extremely obtrusive banner ads.

It's hosted on Angelfire.

What's GeoCities, chopped liver?

Ah, that brings back memories. I loved GeoCities, it's where I first learned HTML.

Cutting off foreign news sources, benefiting large corporations, and making data more easily accessible to European government spy agencies are the primary reasons for GDPR. Helping Europeans? Not an objective.

I wish someone would figure this fucking GDPR thing out and explain it to my boss, because he won't listen to me and I have more important things to do.

Dear Diane's boss:

Shut up and do what Diane says. It's the law now.

Besides, she needs more time to comment on Reason articles - - - - - -

This rule is problematic enough on its own, but because of the vague way that the regulations are written, it is causing online platforms to react in odd ways.

Feature, not bug.

This has inadvertently caught random companies and brands in the snare of Twitter's wide net, who listed the "birthday" of the account as the day that the company was founded. It's annoying, and a little nonsensical, but this is the kind of contortions that online platforms are pushed to in a post-GDPR world.

Remember when the internet became a thing and people thought it wasn't possible to regulate because it "didn't have borders, maaaan".

Anyhoo, I happen to be in Europe this week on business and every fucking site makes me click 'accept' on their page before I can use it. Fun times, and it's the future. I strongly doubt this law will go away.

Remember when the internet became a thing and people thought it wasn't possible to regulate because it "didn't have borders, maaaan".

I 'member, and additionally I figured what would happen is that regulation would go to the country that regulates the most. It's basically the California Rule except now it's the EU Rule, I guess. Geo-fencing is possible, but plenty of content providers find it easier to just adopt the rules of whatever nation has the most regulations since it's often not technically against the rules anywhere else.

I guess the Europeans need to have tariffs to prop up the businesses that they cripple with regulations.

LOL!

Ragnarok Online, on the other hand, decided to simply shut off access to EU players. Only time will tell if this evasive maneuver is enough to keep the potential ?20 million in GDPR fines at bay.

Oh, I expect *those* fines will be actualized.

Only time will tell if this evasive maneuver will result in *additional* GDPR fines.

Face it: If you have data online it's never going to be protected. No regulation can protect it. No security policy can. Act accordingly

We can sure fine you if you fail to comply though.

On the plus side, EU data should sell at a premium on the dark web...

Nice trolling. Doubt it will do any good as far as shaming the EU bureaucrats who came up with this turd, but still.

Not likely. The only thing the EU loves more than regulations are the fines they can levy on anyone who they can claim are in violation, even if they're really not.

Don't be silly.

This is aimed at the non-EU content and will be enforced in that way. This is just another trade barrier riding under an assumed name.

The Internet, and computing in general, was one of the last refuges of freedom from overbearing government meddling. It was nice while it lasted I suppose

What would happen is non-EU businesses with no corporate presence inside the EU simply ignore the GDPR and don't block visits from the EU or black sales to the EU? Is the EU going to block shipments from the companies?

If I have a business in Fargo selling garden gnomes with "Keep ON the grass" signs, and someone from Paris buys one with a credit card and I ship it, and my web site has no GDPR compliance whatsoever, what can the EU do about it?

The EU regulators assert that they have jurisdiction to try you (in absentia if necessary) and to fine you. And given the wording of the GDPR, they'll win easily and assess mind-boggling fines.

The interesting question comes when they attempt to enforce that decision. Since your hypothetical includes no EU presence (facilities, employees, etc), there are no assets that they can attach. They can try to come to the US to enforce their decision but now you'd have to get a US court to agree that their decision in enforceable.

In a just world, the US court would throw the case out on any of several grounds including First Amendment, consent to jurisdiction and contrary to public policy. In the real world, that would probably happen in most courts but you might get unlucky and draw a judge who believes in "data privacy" (without understanding what that really is) and wants to use your case to impose EU-style regulations on evil US companies.

So in my opinion, there is some risk but probably not much. Keep your garden gnome business going. But country-level filtering isn't that hard to set up and could help make the case to your Parisian customers that they need to do something about their own government.

There are laws forbidding enforcement of foreign judgments if those foreign courts do not enforce US sensibilities, but I do not know the details.

Even if they couldn't enforce the judgement here, you'd have to hope you had no interest in traveling to Europe (or anywhere else with stronger enforcement agreements with the EU). You could end up like on of those online poker execs who made the mistake of traveling to the US.

So I expect most small, non-European online vendors will simply cut off access to EU users.

Just pull of stakes and leave Europe. Problem solved.

Who's going to cover the pensions?

Oh, shit, refugees. It's like I don't even watch the news.

Needless to say, this cut off European audiences from significant sources of American news, all because some random regulator decided it was not in their best interest to access it.

Well, obviously. Can't have people in the EU reading relatively unfiltered opinions! It might be hate speech!

I think the author inadvertently discovered one of the actual intents of this massive bit of legislation, not to mention that running everything through Google makes surveillance and identification of government targets a snap!

Exhibit A is Twitter's retroactive banning of users who they believe signed up when they were 13 or younger.

I have it on good authority that this is illegal since these youths may one day visit Trump's twitter feed, and twitter banning these users is infringing on their ability to participate in a public government forum.

I wish to god this was sarcasm, but it is the determination of the U.S. justice system.

Cassius belli. USA .vs EU.

And we can bet on it now - - - - - -

So in a vein similar to the article, but focused on the US, I notice that the internet is still here.

So much for the massive federal takeover of the internet called net neutrality.

Take that, Al Gore!

What is Reason.com gonna do?

Now is the time for international corporations to flex their muscle and show those politicians who is boss.

Just shut down in the EU. Display a page saying you will be back after the voters turn out the evil mean nasty people who passed those unreasonable laws and vote in new guys who will repeal the law.

And while you are at it, suspend all EU government accounts because you can't be sure who is really logged on. Without social media to monitor, they will have to do stuff like help their citizens and all that governing thing.

Welcome to the revolution.

It's important,we can't avoid this policy.

Wishes Magazine