SCOTUS Seems Likely to Overturn Law Banning Sex Offenders From Social Media

"This has become a crucially important channel of political communication," Justice Elena Kagan observes.

Judging from yesterday's oral arguments in Packingham v. North Carolina, the Supreme Court seems inclined to overturn that state's law banning sex offenders from Facebook, Twitter, and other "commercial social networking Web sites." Robert Montgomery, a lawyer from the North Carolina Attorney General's Office, had a hard time persuading the justices that the law—which covers a wide range of sites accessible to minors and applies to all registered sex offenders, whether or not their crimes involved children or the internet—passes muster under the First Amendment.

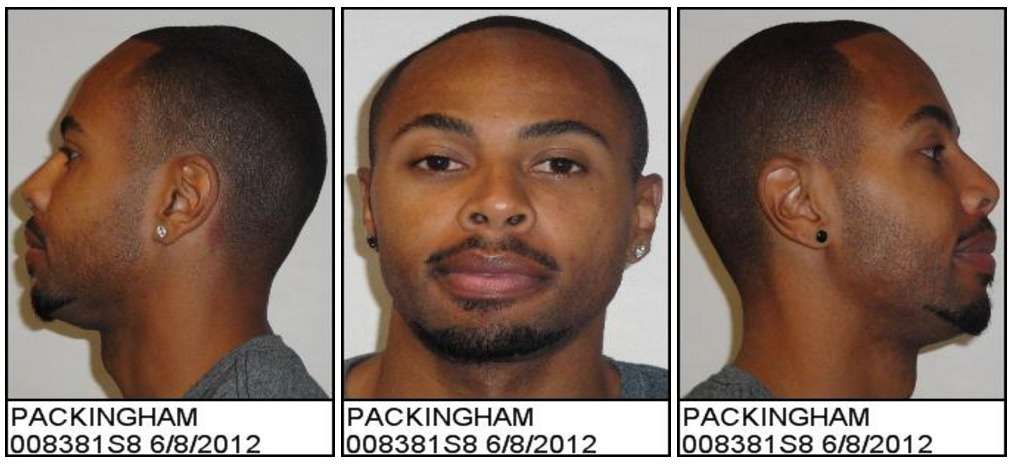

The case was brought by Lester Packingham, who in 2002, at the age of 21, pleaded guilty to taking indecent liberties with a minor. A first-time offender, he received a sentence of 10 to 12 months, after which he served two years of probation and was required to register as a sex offender for 10 years. Six years after Packingham's conviction, the North Carolina legislature passed a law that made it a Class I felony, punishable by up to a year in jail, for a registered sex offender to "access" any commercial website open to minors that facilitates social introductions, allows users to create web pages or profiles that include personal information, and enables users to communicate with each other. Packingham was caught violating the law in 2010, when he beat a traffic ticket and celebrated the event with an exultant Facebook post:

Man God is Good! How about I got so much favor they dismiss the ticket before court even started. No fine, No court costs, no nothing spent….Praise be to GOD, WOW! Thanks JESUS!

Trying to explain how punishing such innocent (and religious!) speech can be consistent with the First Amendment, Montgomery likened North Carolina's law to state bans on politicking within 100 feet of a polling place, which the Court upheld in the 1992 case Burson v. Freeman. "I think that does not help you at all," Justice Anthony Kennedy said, provoking laughter from the audience. "If you cite Burson, I think you lose."

Justice Elena Kagan briefly seemed to be helping Montgomery, only to drive Kennedy's point home. "I agree with you," she told Montgomery. "That's your closest case….It's the only case that I know of where we've permitted a prophylactic rule where we've said not all conduct will have these dangerous effects, but we don't exactly know how to separate out the dangerous speech from the not-dangerous speech….That is like one out of a zillion First Amendment cases that we've decided in our history. And as Justice Kennedy says, there are many reasons to think it's distinguishable from this one."

Justice Stephen Breyer was equally discouraging. "The State has a reason?" he said. "Yeah, it does. Does it limit free speech? Dramatically. Are there other, less restrictive ways of doing it? We're not sure, but we think probably, as you've mentioned some. OK. End of case, right?"

Kagan emphasized the extent of the law's interference with political speech, noting that it prevents sex offenders from following the president, members of Congress, and other elected officials on Twitter or Facebook. "This has become a crucially important channel of political communication," she said. "And a person couldn't go onto those sites and find out what these members of our government are thinking or saying or doing….These sites have become embedded in our culture as ways to communicate and ways to exercise our constitutional rights."

The law clearly covers social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and it arguably applies even to ubiquitous services such as Google and Amazon, which are not primarily social networking sites but seem to meet the statutory definition. Although Montgomery claimed news sources such as nytimes.com are not covered, they might be if they let readers register and create profiles for commenting. "Even if The New York Times is not included," Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said, "the point is that these people are being cut off from a very large part of the marketplace of ideas. And the First Amendment includes not only the right to speak, but the right to receive information."

In addition to a casual disregard for the First Amendment, North Carolina's law illustrates legislators' tendency to impose sweeping, indiscriminate restrictions on sex offenders in the name of protecting children, such as the park ban that an Illinois appeals court recently deemed unconstitutional. Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that North Carolina's social media ban is "being applied indiscriminately to people who have committed a sexual crime of statutory rape—or even if they're teenagers, more than four years apart, or something else of that nature." She questioned "the inference that every sexual offender is going to use the internet to lure a child." She added that someone convicted of "committing almost any crime" might use social media to facilitate a future offense.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Remember when everyone thought SCOTUS was going to rule against Obamacare based on the tone of the oral arguments?

Yes, but I also remember all the times when people correctly predicted the outcomes based on the tone of the oral arguments.

I agree that no one needs to "count their chickens before they hatch". It is a hopeful sign in that the SCOTUS is not just rubber stamping the state's position.

So let me get this straight. SCOTUS thinks that the govt can use residency restrictions to essentially force sex offender registrants to live under a highway overpass, but can't deny them Facebook access?

SCOTUS thinks that the govt can use residency restrictions to essentially force sex offender registrants to live under a highway overpass, but can't deny them Facebook access?

Forcing them to live under a highway overpass means we've got to force them to live under an overpass to the information superhighway too, right?

I think the generation that was worried that kids wouldn't know the difference between cartoons on TV and reality got completely mindfucked by the internet. Even if only like 10% of them bought into the idiocy, it appears to have been more than enough to completely subsume the small percentage who actually knew what the fuck was going on.

I think they ought to apply the same logic to the residency restrictions they seem to be applying to the prohibition against sex offenders accessing and utilizing social media. From my viewpoint, this shows that the nation's highest court is at least looking at one aspect of how far overreaching the sex offender laws are in this nation.

Our legislators haven't forgotten about their oath to uphold the Constitution. It's just that registered citizens are so reviled and have so few advocates that they KNOW they can get away with wantonly violating their rights at every turn. Besides, look at how many make money off of making and enforcing ludicrous laws/rules such as the one under consideration. Sex offender containment is a huge industry where people make money and lots of it.

My only question is how this CLEARLY UNCONSTITUTIONAL "law" became a law in the first place? Can anyone in NC READ?!? You don't have to be a lawyer to see this is a BLANTANT violation of the 1A.....

What we need is an enforcement mechanism for those oaths they take to uphold the constitution. Legislators seem to forget that part of the job.

We have one -- elections.

Which might work if voters gave a shit about constitutions.

If the people don't give a shit about the constitution, then it's game over.

Well, it was fun while it lasted, I guess. If voters do care, it sure doesn't show in how they choose to vote.

The problem is that while many give a care about the Constitution, they simultaneously want the power to selectively decide who is and isn't worthy of constitutional protections. They'll fight tooth and nail for their rights, but sex offenders' rights be damned.

Your action in this place has been witnessed.

If it were more narrowly tailored they probably could have gotten away with it. Had the ban been on interacting on the Internet with people who appear to be minors, it probably would have been upheld.

Here's the thing though. This will be an important win because it will dial back state authority to stifle free speech and free access to information. However, Facebook has their own policy that forbids sex offenders from maintaining accounts, so even if they win, someone would have to sue Facebook for discrimination and force them legally to stop banning sex offenders from their site.

She added that someone convicted of "committing almost any crime" might use social media to facilitate a future offense.

Exactly. BAN THE INTERNET!

They why are they fucking out of jail then?

It seems to me that if you can forbid someone from using a particular communication channel, you could forbid them from speaking or communicating at all.

I've said it before and I'll say it again. If anyone is too dangerous to go walking in a public area (like a park), or if you are too dangerous to go online, you should be in jail.

If you are out of jail that means you are not a threat to the public anymore.

I've said it before and I'll say it again. If anyone is too dangerous to go walking in a public area (like a park), or if you are too dangerous to go online, you should be in jail.

Disagree, slightly. "Being too dangerous to go online, therefor jail." is a non sequitur. Forbade from using the internet for (certain forms of) social or economic *exchange*? Maybe.

I could only support a prohibition against sex offenders using sites like Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, etc. if it were applied strictly and without exception on an individual basis only to those offenders who used social media to commit their crime(s). There should not be a blanket prohibition against accessing the Internet or social media. Only when it is a matter of the record that an individual offender used the Internet to commit their crime(s). To wit: distributing child pornography, using social media to contact, groom, and abuse their victim(s). For all others rules governing use of social media should be limited to forbidding contact with minors for those offenders who target teens and prepubescent children and the viewing, downloading, and trading of child pornography. Narrowly tailor the rule only to prohibit these specific criminal acts.

This might also tie a stronger First Amendment concern to Internet access for sex offenders in general. I know for a fact in my state violent sex offenders (rapists and child molesters) are subject to lifetime supervision, which is parole-style supervision for sex offenders AFTER they complete their prison sentences. Violating one of the terms of supervision is a class a misdemeanor even if the act is not criminal in and of itself. (Such as going on Facebook). The T.D.O.C. as a rule bans sex offenders from even having Internet Access period unless they are in school or have a job that requires Internet access. By tying a First Amendment interest to accessing social media by default puts a free speech liberty interest on Internet access as well. The ironic thing about the TN Dept. of Corrections' routine outright ban on Internet Access for recreational purposes for sex offenders on lifetime supervision is that there is no statute on the books that strips Internet access from sex offenders. It's supposedly the officer's discretion, but my research has found out that the field offices have a blanket policy that bans recreational Internet Access for sex offenders, even if their crimes of conviction did not rely on access to the Internet as an instrument of the crime.

I think the ban would be upheld if states had limited the ban only to those offenders who have a proven track record of using social media to contact, groom, and abuse/attempt to abuse their victim(s). Only if the crime involved the use of social media should a prohibition be put in place ON A CASE BY CASE BASIS.