SCOTUS Will Consider Challenge to Ban on Social Media Use by Sex Offenders

A man arrested for using Facebook argues that North Carolina's law violates the First Amendment.

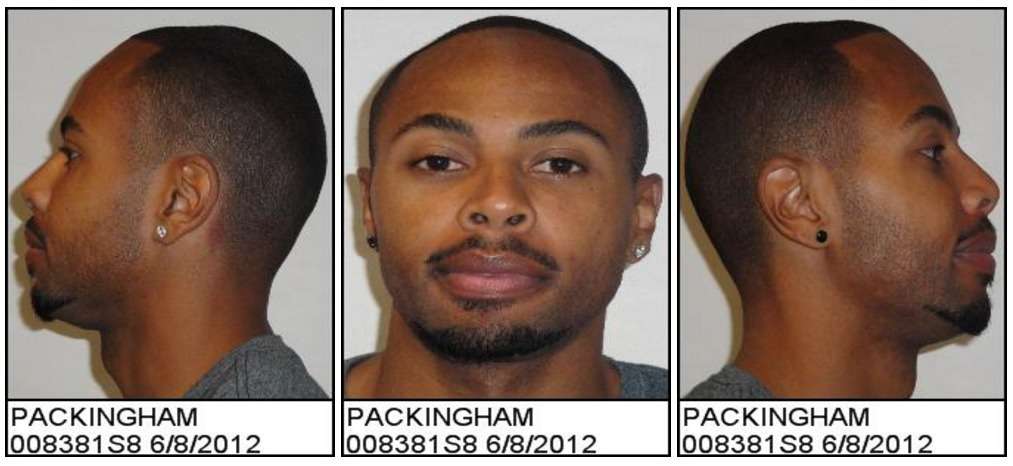

After beating a traffic ticket in 2010, Lester Packingham exulted on Facebook: "Man God is Good! How about I got so much favor they dismiss the ticket before court even started. No fine, No court costs, no nothing spent….Praise be to GOD, WOW! Thanks JESUS!" That burst of exuberance led to Packingham's arrest and prosecution, because as a registered sex offender in North Carolina he was prohibited from using Facebook or any other "commercial social networking Web site." Last Friday the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear his First Amendment challenge to that rule.

In 2002, when he was 21, Packingham pleaded guilty to taking indecent liberties with a minor. A first-time offender, he received a sentence of 10 to 12 months, after which he served two years of probation. He was required to register as a sex offender for 10 years. Six years after Packingham's conviction, the North Carolina legislature enacted a law that made it a Class I felony, punishable by up to a year in jail, for a registered sex offender to "access" any commercial website open to minors that facilitates social introductions, allows users to create web pages or profiles that include personal information, and enables users to communicate with each other. That restriction applies to all sex offenders listed in North Carolina's registry, whether or not their crimes involved children or the internet and no matter how long ago they occurred. The law clearly covers social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and it arguably applies even to ubiquitous services such as Google and Amazon, which are not primarily social networking sites but seem to meet the statutory definition.

A unanimous state appeals court agreed with Packingham that the law he broke violated his First Amendment rights. Applying intermediate scrutiny, the court concluded that the law "is not narrowly tailored, is vague, and fails to target the 'evil' it is intended to rectify" because it "arbitrarily burdens all registered sex offenders by preventing a wide range of communication and expressive activity unrelated to achieving its purported goal." The North Carolina Supreme Court reversed that ruling in a 4-to-2 decision last year, finding that the law is mainly aimed at conduct, affecting speech only incidentally, and is narrowly tailored to achieve the state's goal of preventing sex offenders from "prowling on social media and gathering information about potential child targets."

The court also concluded that the law leaves open "ample alternative channels for communication," since it exempts sites that bar minors, that are designed mainly to facilitate commercial transactions among users, or that provide a single discrete service such as email, photo sharing, or instant messaging. While Packingham could not legally use Facebook or Twitter, the majority noted, he was still free to swap recipes on the Paula Deen Network, post photos on Shutterfly, look for a job at Glassdoor.com, or get news updates from the website of WRAL, the NBC station in Raleigh, since all of these sites officially limit registration to users 18 or older.

UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh, who worked on a friend-of-the-court brief urging the U.S. Supreme Court to take up the case, questions the state court's understanding of "ample alternative channels," a requirement for applying intermediate rather than strict scrutiny to limits on speech:

How can a total ban on some people's use of Facebook, Twitter and the like be said to leave open "ample alternative channels"? [According to the North Carolina Supreme Court,] the people restricted by the law can't read or post to Facebook, Twitter and so on. But no problem—the sex offender still has ample alternative channels, such as the Paula Deen Network, WRAL.com, Glassdoor.com and Shutterfly. The state has argued that the North Carolina Supreme Court focused on the Paula Deen Network because the defendant argued, in part, that he couldn't use certain other food-related sites. But the defendant also argued that he couldn't use Facebook and the other giants, and the court didn't—and couldn't—explain how the Paula Deen Network and the other sites constitute an ample alternative to those massive social networks.

In her opinion dissenting from the North Carolina Supreme Court's ruling, Justice Robin Hudson argues that the law barring registered sex offenders from social networking sites primarily targets speech, not conduct, and that it is arguably not content-neutral, meaning that strict scrutiny should apply. In any case, she says, the fit between the law's restrictions and its goal is so loose that it cannot survive even intermediate scrutiny.

Although "the State's interest here is in protecting minors from registered sex offenders using the Internet," Hudson notes, "this statute applies to all registered offenders," as opposed to "those whose offenses harmed a minor or in some way involved a computer or the Internet," or "those who have been shown to be particularly violent, dangerous, or likely to reoffend." She also argues that the law "sweeps far too broadly regarding the activity it prohibits." The definition of a social networking site "clearly includes sites that are normally thought of as 'social networking' sites, like Facebook, Google+, LinkedIn, Instagram, Reddit, and MySpace." But it "also likely includes sites like Foodnetwork.com, and even news sites like the websites for The New York Times and North Carolina's own News & Observer." The law "may even bar all registered offenders from visiting the sites of Internet giants like Amazon and Google."

Packingham v. North Carolina provides an opportunity for the Supreme Court to address important First Amendment issues such as the meaning of "ample alternative channels" and the distinction between conduct and speech regulation. It also gives the Court a chance to reconsider its reflexive deference to state legislators whenever they purport to be protecting children from predatory perverts. Under North Carolina's law, someone who has never shown any propensity to molest children or stalk them on the internet, such as a teenager who exchanges nude photos with his girlfriend, is prohibited from visiting many highly popular and useful websites. His punishment for using Facebook or Twitter might even be more severe than the penalty for his original offense. That is what passes for common sense in laws dealing with sex offenders.

Show Comments (45)