Alabama Cops, Confederate Flags, Racism, and an Over-Eager Media

Despite unsubstantiated claims that police planted evidence on black men, credible accusations of systemic racism and police malfeasance remain.

Last month, dozens of news outlets shared a "bombshell" story about a cabal of neo-Confederate police officers in Dothan, Alabama. The officers had allegedly been systematically planting evidence on innocent black men for decades, resulting in hundreds of wrongful convictions.

But soon after the article was published, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC)—the entity whose endorsement most likely helped the story go viral—issued a retraction on Twitter. The SPLC also released a statement to AL.com reading, "We received new information from people we trust around Alabama that we should be highly suspect of the reporting and then made the decision that we didn't want to keep the story out there under our account."

The original story was indeed overcooked. But after examining court documents and historical archives, as well as speaking with the story's author, several former Dothan police officers, and an anti-Confederate historian, I found that Dothan does have serious, long-standing, and unresolved race issues. And this continuing racial strife manifests itself within the police department, where some white officers share the view of many Southerners that the Confederacy is a misunderstood and victimized part of their "heritage" and some black officers feel targeted by a harsher and less flexible application of the law.

Unfounded Outrage

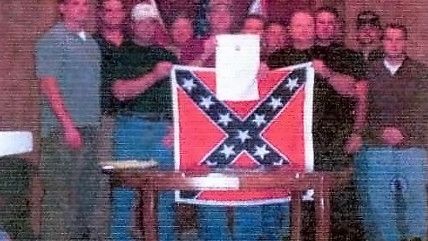

Jon B. Carroll, writing in the Henry County Report blog, asserted that he was publishing documents leaked to him by current and former Dothan police officers that "served as irrefutable evidence of criminal activity at the highest levels of the Dothan Police Department" and also implicated several chiefs of police and the district attorney in a coverup. With its provocative headline, loaded language, and accompanying photo of a group of white men proudly displaying a Confederate battle flag, the story made for effective clickbait, and it was shared more than 127,000 times in the day after it was published.

But the documents Carroll published don't provide irrefutable evidence of the alleged crimes at all.

Too many details and names have been redacted. One of the typewritten documents purportedly written by a group of whistleblowing officers is unsigned (supposedly because of fears of retaliation, but unsigned nonetheless). Another document written to the U.S. Attorney's office from "Concerned Police Officers" is block-written and unfolds in almost incomprehensible English. Nothing in the documents offers proof that even a single officer planted drugs or that any crimes were covered up by senior officials. Furthermore, one of the documents plainly states that District Attorney Doug Valeska was advised of an officer's failure to maintain lawful custody of drug evidence and had "a problem bringing the suspects in drug cases to trial" due to the officer's credibility issues.

Carroll describes himself as a "citizen journalist" and admits that his goal is to create sufficient outrage to warrant a federal investigation into the Dothan Police Department and District Attorney Valeska. He says the documents were leaked to him by one active-duty Dothan police officer and three former officers, and more will be released over time once they've been subject to additional vetting.

Yet Carroll does himself and the cause of criminal justice reform no favors when he writes hyperbolic passages, which he has thus far failed to prove, like this:

The larger issue is no less than hundreds of wrongly convicted black men and tens of millions of dollars in potential damages as well as potential prison terms for himself and the district attorney and those who assisted them.

Dothan's Police Chief Steve Parrish angrily denied Carroll's claims at a press conference a day after the article went viral, stating, "There are simply too many outright lies and fabrications in the blog to address individually, but his 'opinion' has apparently been taken by many as 'fact.'"

Former Police Chief John White—who is accused in the article of giving misleading testimony under oath and ordering internal affairs investigations "buried"—told me that Carroll is an "idiot webmaster" who never called him to confirm or clarify anything. White categorically denies all the allegations made against him, and says he intends to file a notice of defamation against Carroll. However, White also conceded to me that all the documents containing Dothan Police Department letterhead are completely authentic, including documents revealing that a number of officers raised concerns about at least one officer suspected of "planting drugs."

Compromised Drug Evidence

Much of of the follow-up reporting by other publications has—understandably—focused on Carroll's questionable allegations. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that something is truly rotten in Dothan.

The focal point of Carroll's article is the internal investigation of Officer Michael Magrino, who was fired after then-Sergeant Keith Gray recommended his dismissal. Gray had concluded that Magrino "lost his integrity as well as his credibility due to drug evidence being missing."

Magrino now works as an investigator for an Alabama state agency and would not comment for this story.

Another published document reveals that Magrino was given a polygraph test in which he was asked questions including, "Have you planted any illegal evidence?" The results of the test indicated a probability of deception greater than 99 percent.In the Internal Affairs (IA) report, Gray wrote:

There are at least 50 case folders that contain drugs that should have been submitted to the Property/Evidence Officer for storage and chain of custody issues. Some of those cases have been in Magrino's possession for over two years.

There are five handguns, one of which was still listed as stolen, one which Magrino lost for a period of time then it reappeared under suspicious circumstances, and two handguns that he has no idea where he seized them from.

In a phone interview, Magrino's former boss, ex-Chief John White, describes Magrino as a "good cop" who was "sometimes lazy." White characterizes Magrino's indiscretions as a mere matter of failing to follow procedure, noting that all the drug evidence observed in his cruiser by a supervising officer was "bagged and tagged." Magrino simply hadn't submitted it into evidence at the station yet.

Gray, the author of the IA report on Magrino, explains to me over the phone that "drugs are illegal for anyone to possess, including police officers. Drug evidence must be turned in immediately." He adds that any failure to follow evidentiary procedure is enough for a defense attorney to argue for reasonable doubt before a jury. In Magrino's case, there are literally scores of cases potentially compromised.

White, who says it's a shame Magrino was fired for what he believes are minor indiscretions, describes Gray as a "disgruntled ex-cop" who was fired because of what White calls his association with a "black motorcycle gang involved in bar fights." It's a telling example of the underlying racial tension in Dothan, where some blacks feel powerless against an entrenched good-ole-boys system that prosecutes them to the letter (and sometimes beyond) of the law.

Fired For Being a Black Biker?

Before his dismissal, Gray had risen to the rank of captain and was the highest-ranking black officer in the history of the department, with aspirations to become Dothan's first black police chief.

Dothan's history of racial discrimination is well-documented.

In 1976, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama Southern Division case of Wiggins v. Hollis was one of several federal lawsuits which found "there has been and still remains a substantial and pervasive racial discrimination in Dothan … governmental services have been disproportionately bad in the black areas." The judgement of Wiggins v. Hollis imposed a consent decree on the city, which is still in effect, requiring "an affirmative duty to provide blacks with their proportionate share of government services … in order to remedy the effects of past denial to blacks of access to the political process."

The consent decree led to the integration of Dothan's police department, with the hiring of two black officers later that year.

Writing in The Washington Post, Radley Balko shares the insight of one of his sources with knowledge of Dothan:

One prominent defense attorney in the state says the county is so rife with racism that he had advised black clients to take plea bargains even when they have corroborating witnesses, simply because white jurors there just tend to assume that black people are lying. He described the racism in the area as so casual and ingrained that the people who practice it are unaware of it. "It's the scariest kind of bigotry," he added.

Which brings us back to the motorcycle gang that White says was the reason for Gray's firing.

In 2008, Gray founded a motorcycle riding club called the Bama Boyz. The group

had never been involved in any criminal activity and had even donated money to the department's youth athletic league. But three weeks after Gray filed an Equal Employment Opportunity complaint against the department, his membership in the Bama Boyz was used to trigger an Internal Affairs investigation of him. The investigation concluded with Gray's termination for "conduct unbecoming of an officer," with specific allegations that he had downloaded pornography on a department-issued phone (though the department never produced such a phone for independent forensic testing) and that through his affiliation with the Bama Boyz, he had associated with known criminals in another biker club, called Outcast.

According to court documents, Gray had limited contact with a leader of the outlaw biker club Outcast, ostensibly as a means of avoiding conflict. Outlaw bikers are known for physically harassing or intimidating riders who pass through their territory, and the career lawman preferred to nip such a potential issue in the bud by essentially asking for permission to ride in Outcast-dominated areas.

Three weeks after Gray filed his EEO complaint, a bar fight involving members of Outcast broke out. Gray was accused of consorting with known criminals, even though no evidence was presented that Gray or any members of the Bama Boyz were anywhere near the incident in question. Ultimately, this scrum was the main pretext for his dismissal from the force.

Gray has since filed a federal lawsuit against the department, where he alleges that other officers had called him the "N word" and used the word casually in his presence. Also documented in the suit are Gray's allegations that his most recent superior officer, Chief Steve Parrish, presided over "an office culture that set pro-Confederacy viewpoints on proud display" and that the prerequisites for the job of police chief were repeatedly changed to allow less-qualified white candidates to assume the role, though he had certain qualifications (such as a Master's degree) that were previously required.

The city asked for the suit to be dismissed, but Judge Myron Thompson rejected the city's request. "That race discrimination was, at least, in play at the time of his discharge is a reasonable inference," Thompson wrote.

Another Black Officer Suspended

Gray isn't the only former Dothan police officer engaged in litigation against the city. Raemonica Carney, an officer with the department from 2000 to 2013, filed a lawsuit alleging racial discrimination, violation of right to freedom of speech, creating a hostile work environment, and retaliation. The 13-year veteran was the public face for the department's Community Watch program from August 2010 until May 2013, when she was suspended for making controversial statements on Facebook.

In these posts, which she has since made private, Carney wrote about Christopher

Dorner, the black ex-police officer who killed himself after a massive manhunt following what is widely believed to be a killing spree where he shot a number of people, including cops, in Los Angeles. Carney appeared to indicate she believed Dorner's claims of racism and corruption in the Los Angeles Police Department might have some validity. She also questioned the police's tactics, which included shooting innocent people, during the manhunt.

After 13 fellow officers, all white, filed written complaints over the posts—described by then-Police Chief Greg Benton as "sickening and disturbing"—Carney was suspended. Later that year, she was fired for gross insubordination following an incident with superior officers during a domestic disturbance outside her home.

It's no secret that Carney has an ax to grind with the Dothan Police Department. She says she has been repeatedly harassed by members of the force both during and after her time on the job, and believes the Dothan police exacted retribution on her by planting drug paraphenalia on her son during an arrest where he was stopped without probable cause. She provides no evidence to substantiate her accusation, however, and she couldn't recall if her son ever made this claim in court when defending himself against the charges. Carney explains that she never went to his court appearances because she didn't want to present the appearance of interfering with the case.

In a phone interview, Carney says that several of her Facebook statements were taken out of context and some were responses to other people. But the excerpts chosen by her superiors were designed to make her appear as if she supported Dorner's alleged crimes, although that was never the case, she says.

In March 2014, Carney's lawyer, Sonya Edwards, told the Dothan Eagle: "She is being retaliated against for exercising her rights. We all know much worse has been done in this department without it even being determined to be insubordinate, much less grossly insubordinate. She is being terminated under a policy that, effectively, does not exist. There is no benchmark. It is a highly subjective standard."

Carney was born in 1972 and lived in Dothan her whole life except for a stint in the army and jobs with two police departments in Georgia from 1993-1999. She says she left Dothan in 2014 shortly after her termination, fearing for her safety. "The racism in Dothan is systemic and has been the norm for so many years," Carney says.

Confederate "Heritage"

The most striking image in Carroll's article is the photo (also seen at the top of this page) of a group of Dothan police officers, including current Chief Steve Parrish, posing with the stars and bars to commemorate their membership in Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), which they describe as a "heritage" and "history" group. Parrish admits that when starting the Dothan chapter of the SCV, he needed to meet a minimum number of members so he recruited from within the department. But asked about his former membership in the group, Parrish also says he stopped participating in 2005.

There is considerable debate as to what the SCV stands for. Carroll writes that the

Souther Poverty Law Center has labeled them "racial extremists," though what the SPLC actually described in 2002 was an "internal civil war between racial extremists and those who want to keep the Southern heritage group a kind of history and genealogy club."

Edward Sebesta, the co-editor of The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The "Great Truth" about the "Lost Cause," says the conflict within the SCV a decade ago was "more between those who thought it wouldn't be a good idea to be upfront with their political and racial ideas and those who were willing to be quite frank about their racial and political ideas."

Sebesta took issue with the idea that the group could be affectionate toward the Confederacy without racial malice. "Think about what the Confederacy was—a violent insurrection to preserve white supremacy and slavery," he says. "How much value can you place on the human worth of African Americans if you choose to have affection for the Confederacy? Why would the Confederacy seem attractive or something you would want to be affectionate towards if you had any sense of African Americans having human worth?"

Sebesta sent me a trove of back issues of Southern Mercury and The Confederate Veteran, two print-only magazines published by the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, where statements of white Anglo-Saxon supremacy and essays about Jewish/Marxist conspiracies to destroy white Southern culture are frequently couched with defensive rejoinders.

In the July/August 2006 issue of Southern Mercury, Michael Masters wrote an article called "The Tolerance Scam," where he contends that accusations by "cultural Marxists" that the SCV's beliefs are "grounded in hate" are "baseless," and that the major civil rights reforms of 1950s and 1960s were akin to "using the sledge of anti-racism as a battering ram to bring down the walls of traditional Western culture."

In a 2003 issue of Southern Mercury, Frank Conner characterized the idea that blacks and whites are capable of equal intelligence as a liberal conspiracy, blaming one "liberal cultural anthropologist" for having falsely "decreed that there were no differences in IQ among the races, and the only biological differences between the blacks and white were of superficial nature." Conner laments that this created "a false image of the blacks in America as a highly competent people who were being held back by the prejudiced white southerners."

Despite the SCV's condemnation (which appears on its website) of those "who espouse political extremism or racial superiority," the SCV has never disavowed any of the articles or the racist ideas in the magazines they've published within the past decade and a half. In fact, they still frequently cite and promote Conner's book The South Under Siege, which claims that the civil rights movement was part of a conspiracy to "install a socialist government in the U.S., to be run by Jews."

During the same press conference where he denied allegations of corruption, Parrish offered the following explanation for his membership in the SCV. "I'm a history enthusiast," he said. "Genealogy is what I've studied—my lineage. My ancestors fought for the South in the Civil War. I'm proud of that. If that makes me a demon, I'm sorry."

It is difficult to swallow explanations that the SCV is a perfectly innocent heritage community, however, when a black officer can be suspended for Facebook comments that make white officers uncomfortable. Surely Confederate imagery and open recruiting for a group with the kind of views endorsed by the SCV is enough to make a great number of officers, not just blacks, understandably uncomfortable.

Similarly, if open membership in a private motorcycle club (one deemed sufficiently legitimate for the police department to accept charitable donations from it) is enough to get the highest-ranking black officer in the history of the department fired, then what should be said of a group of senior officers displaying Confederate imagery within the police department and openly recruiting for a group that endorses ideas of white superiority? These instances of seemingly unequal application of departmental policy are well worth confronting.

Still, none of this proves the sort of widespread abuse charged in Carroll's article. Despite the stir caused by the viral dissemination of the piece, no evidence has yet been produced that anyone—much less hundreds of people—was wrongfully convicted on bogus drug charges. And while some journalists (Liliana Segura of The Intercept, Andrew Cohen of The Marshall Project, former Reasoner Radley Balko) issued mea culpas for disseminating Carroll's flawed article, others doubled-down on the bad information.

The online news show The Young Turks ran an 11-minute segment where the hosts frequently embellished and mischaracterized the contents of the documents while advocating for life imprisonment for the officers implicated. Former Air America Radio host Sam Seder's current show at The Ring of Fire egregiously headlined their segment on the story, "Neo Nazi Alabama Cops Have Been Framing Black People For Years." Nowhere in the original article does the word "Nazi" ever appear, and creating the false impression that such evidence has been presented only undermines the work of those who advocate for transparency in government and criminal justice reform. For many of those who ran with the story, a vigorous exploration of the facts was beside the point, because Carroll's story seemed to perfectly fit a narrative of systemic racism and abuses by a police force in the Deep South that many of them simply wanted to believe.

None of this, however, means there isn't substantial evidence of race-based double standards being practiced by the Dothan police department. Nor does it mean that accusations of police abuses against black residents should be dismissed out of hand. It's worth keeping an eye on Dothan, so long as we're careful to examine the evidence behind the headlines before jumping to conclusions.

Show Comments (179)