Which States Will Legalize Pot Next?

A preview of the marijuana initiatives that voters can expect to see in 2015 and 2016

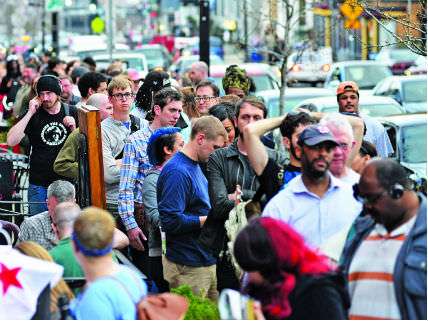

At the beginning of 2014, when Colorado became the first state to allow the sale of marijuana for recreational use, the whole world was watching. "It was insane," says Toni Fox, owner of Denver's 3D Cannabis Center, where the first sale happened. "On January 1, there were close to 200 reporters here. Controlled chaos. It was just packed with reporters."

But the more successful Colorado's model is and the more imitation it inspires, the less attention it will get. "Colorado is not going to be the top dog for much longer," says Kayvan Khalatbari, co-owner of the Denver Relief dispensary. "I think it's only a matter of time before Colorado really gets overlooked."

Khalatbari predicts that "up to a dozen states" will have legal marijuana by the end of 2016, which may not be far from reality. Last year Alaska, Oregon, and the District of Columbia joined Colorado and Washington, where voters also approved legalization in 2012. Similar ballot initiatives have a decent or better chance of succeeding in at least half a dozen states this year and next. These are the ones to watch:

Ohio

The constitutional amendment sponsored by Responsible Ohio is the one legalization measure that is expected to be on the ballot in 2015 rather than 2016. The Marijuana Legalization Amendment designates 10 sites owned or controlled by its financial supporters—who include Columbus real estate developer Rick Kirk, fashion designer Nanette Lepore, former NBA player Oscar Robertson, and former NFL player Frostee Rucker—as the only places where commercial production will be allowed, at least initially.

That marijuana minyan has been controversial. "How [does] creating a cartel benefit anyone besides the people who profit from it?" asked a member of the audience at a February forum sponsored by the Central Ohio chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that "the room erupted in applause." Ohioans to End Prohibition, a competing group aiming for the 2016 ballot, calls for "a free market in legal marijuana." Under its measure, the group says, "any adult or corporation will be able to apply for and purchase commercial licenses to grow, manufacture, or sell marijuana and marijuana products."

In February, responding to criticism of its locked-down approach to cannabis cultivation, Responsible Ohio decided to include "regulated and limited home growing" in its initiative. The amended version of the measure allows adults 21 or older to grow up to four flowering plants and possess up to eight ounces at home for personal consumption, provided they obtain state-issued licenses. That change moved the Ohio initiative closer to the laws in the jurisdictions that have legalized marijuana so far: Except for Washington state, they all allow home cultivation. Also like the earlier state initiatives, Ohio's allows adults to possess an ounce or less of marijuana in public. It prohibits consumption in "any public place," which it does not define.

Responsible Ohio spokeswoman Lydia Bolander says the initiative's limit on commercial producers is designed to facilitate regulation and ensure that "those individuals are ready and willing to start production as soon as possible." She adds that there will be many other opportunities for people to make money in the newly legal cannabis industry. The amendment, Bolander says, allows "one retail store per 10,000 residents statewide, which would give us about 1,100 retail stores that could be licensed throughout the state." (By comparison, Washington, with a population about 40 percent smaller than Ohio's, initially planned to license just 334 recreational retailers.) Bolander adds that newcomers are welcome in edible manufacturing, pot testing, and "peripheral businesses in the supply chain."

Local governments also stand to benefit financially from marijuana legalization, since they will get 85 percent of the revenue from the taxes specified in the amendment: 15 percent of gross revenue received by growers and marijuana product manufacturers, plus 5 percent of gross revenue received by retailers. By contrast, the states that have legalized marijuana so far are taxing it based either on price or weight. "You can't play a game with what your gross revenue is," Bolander explains, "and that ensures that the tax revenue will be collected and it will go where it's supposed to go."

If voters approve the constitutional amendment, which in Ohio requires only a simple majority, it will be the first time a state without a medical marijuana law legalizes the drug for general use. Under current law, possessing even the tiniest amount of marijuana, no matter the reason, is a misdemeanor; as little as 100 grams (about 3.5 ounces) can lead to a jail sentence; and twice that amount is a felony. It's not clear whether Ohioans are ready to leap from that system to one in which not only consumption but production and distribution (provided they are authorized) do not trigger any punishment at all.

A Quinnipiac University poll conducted in March found that 52 percent of Ohio voters thought adults should be allowed to "possess small amounts of marijuana for personal use," which is not quite the same as legalizing commercial production and distribution. "Our internal polling has definitely shown that there's very strong support for full legalization," Bolander says, "and we're confident that that number's only going to continue to grow between now and November."

Rob Kampia, executive director of the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP), thinks it's risky to put a marijuana initiative on the ballot in a year when people are not electing a president, since turnout is lower then, especially among the younger voters who are most likely to favor legalization. He worries that a defeat in Ohio could be portrayed as a reversal of the movement's momentum. "That failure will be the only failure in the country," he says, "and then the media will feed on that: 'Oh, my God, legalization is backsliding.''Š"

Bolander counters that an off-year election in Ohio has advantages. "Ohio in a presidential year, the political noise is just cacophonous, and you really cannot have a conversation about another issue that isn't influenced by political dynamics that are outside of your control," she says. "Rather than trying to have that conversation in a year when we're also talking about a presidential race, a Senate race, and numerous other congressional and local races at the same time, this is going to give us a unique platform to be able to have a bigger conversation about why this is such an urgent necessity for Ohio."

Nevada

As I write, Nevada, where voters will decide whether to legalize marijuana next year, is the only state where an initiative already has qualified for the ballot. Like Colorado's Amendment 64, the Initiative to Regulate and Tax Marijuana would make it legal for adults 21 or older to possess up to an ounce in public, grow up to six plants at home, and transfer up to an ounce at a time to other adults "without remuneration." The initiative charges the state Department of Taxation with licensing and regulating marijuana producers, distributors, and retailers. It imposes a 15 percent excise tax on the "fair market value" of marijuana sold by growers.

Consuming cannabis in a marijuana store, "a public place," or a moving vehicle would be a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $600. The initiative defines "a public place" as "an area to which the public is invited or in which the public is permitted regardless of age," which suggests that, as in Alaska, age-restricted establishments (other than marijuana stores) could allow cannabis consumption on their premises. That option would distinguish Nevada from Colorado and Washington, where the rules governing consumption outside the home remain fuzzy.

Nevada, like all the states that have legalized cannabis for recreational use, already has medical marijuana. As in Colorado, dispensary owners would have the option of switching to the new market.

Kampia, whose organization is backing the Nevada initiative, notes that legalization measures were supported by 39 percent of Nevada voters in 2002 and 44 percent in 2006. "Both of those were mid-term elections," he says, "so the numbers would automatically be lower than if we had done the presidential elections. That was something that I've learned not to do again. Presidential elections are just superior for marijuana." Last February an MPP-sponsored poll put support for legalization in Nevada at 54 percent.

"We consulted with most of the gaming moguls while we were drafting the Nevada initiative," Kampia says, and "they just said that if we abided by a few of their basic requests, like not allowing people to smoke pot on the Las Vegas Strip, then they probably wouldn't care that much about the initiative." One gaming mogul who might care: billionaire Sheldon Adelson, a major Republican donor who last year helped defeat Florida's medical marijuana initiative by giving more than $5 million to the opposition. "Sheldon Adelson lives in Nevada," says Kampia, "so he could write a check for a couple of million dollars and make that campaign very difficult."

California

It may seem puzzling that California, which blazed the medical marijuana trail back in 1996, has not legalized recreational use yet. The state's last legalization initiative, Proposition 19, fell four points short of a majority in 2010, just two years before legalization won by 10 points in Colorado and 11 points in Washington. "Partly it was a case of premature ejaculation," says California NORML coordinator Dale Gieringer, who is working with ReformCA, a.k.a. the Coalition for Cannabis Policy Reform, to produce an initiative for the 2016 ballot. "The 2010 initiative, which I was very much against writing in 2010, was just too soon, and it was an off-year election." He adds that "the language had not really been discussed and vetted adequately" and "there wasn't a broad coalition working on it."

ReformCA, which needs to finalize its initiative's language by July, hopes to avoid those pitfalls. "The most difficult question that we face at the moment is medical marijuana regulation," Gieringer says. "It's been sort of an ongoing scandal in California that the state has not really come up with any clear regulatory guidelines on medical marijuana." The legislature is trying again this year, he says, and it's important that whatever it produces, assuming it produces anything, be "compatible with our plans for the initiative." The problem is that legislators have until October to pass a bill and get it signed by the governor, meaning they may act after the initiative is finalized.

"We have to come up with something that is compatible with California's longstanding cannabis growing culture," Gieringer says. "Whatever we come up with is going to be devised in a way to accommodate as much as possible all of those growers, many of them outdoor growers who have been around for a long time, and give them an opportunity to participate."

Kampia, whose organization also is backing the ReformCA effort, is not sure it makes sense to tackle medical marijuana. "The advantage to including the regulation of medical marijuana is that it would allow the existing medical marijuana people to find a more legal way of being involved with medical marijuana and not being in a gray area if they wanted to move out of the gray area," he says. "A disadvantage is that it complicates the campaign message, because then you're talking about two separate things in the same campaign."

Gieringer also would like the initiative to address the question of where, aside from private residences, people are allowed to consume cannabis. Kampia says voters might not go for that. While "people who support legalization prefer for there to be opportunities to use marijuana socially in public settings, such as bars or marijuana-specific coffee shops like Amsterdam's," he says, allowing consumption outside the home "also raises concerns that the opposition will say there's going to be more people smoking and driving."

The Blue Ribbon Commission on Marijuana Policy, a panel created by the American Civil Liberties Union of California and chaired by Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom (who supports legalization), identifies road safety as one of the major issues that need to be addressed if voters decide that marijuana should be treated more like alcohol. But Gieringer does not think the initiative should change California's approach to driving under the influence of marijuana. Current law requires evidence of impairment, which can include drug test results, but California does not have a per se definition based on the level of THC in a driver's blood. Such definitions are highly problematic, because there is no clear association between specific THC concentrations and driver performance.

Washington's initiative included a per se rule that equates impairment with five nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood, a cutoff that in practice means many regular users can never legally drive, even when they are not actually impaired. Colorado's initiative did not address the issue, but after voters approved it the state legislature enacted a rule similar to Washington's. The initiatives in Alaska, Oregon, and Washington, D.C., left laws regarding stoned driving unchanged. In Gieringer's view, so should California's.

"I don't see any need to touch it," he says. "This year, for the first time in several years, there's no zero tolerance DUI bill in the California legislature, partly because all of the dire predictions about an epidemic of DUIs in Colorado and Washington have not panned out." He also notes that a landmark study released by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in February "pretty much concluded there's no scientific way of determining whether someone is DUI, at least based on existing technology of drug testing."

A March survey by the Public Policy Institute of California found that 55 percent of the state's likely voters think taxing and regulating marijuana is preferable to banning it. That was the highest level of support for legalization found by the organization since it started asking the question in May 2010.

Although opponents of legalization initiatives typically have not managed to raise much money, Kampia thinks California might be different. "First of all, the opposition tasted victory in Florida," he says. "Also, California's the only state that's consistently had major opposition money to its serious criminal justice reforms. The narcotics officers and the prison guards in California have real money, and they're willing to spend it."

Massachusetts

In 2008 Massachusetts voters approved marijuana decriminalization by a margin of nearly 2 to 1. Under that initiative, possession of up to an ounce became a civil offense punishable by a $100 fine. Four years later, a similarly large majority approved medical use of marijuana. Are Bay Staters ready to go all the way? MPP, which is backing a 2016 initiative that has not been written yet, thinks so.

"Decriminalization was more popular than almost every politician in the state," Kampia says. A Boston Herald poll conducted in late January and early February 2014 found that 53 percent of likely voters favored legalization, while a Boston Globe poll last July put support at 48 percent. Kampia calls those results "stale," noting that more recent surveys have found that something like 52 percent of Americans think marijuana should be legalized. "The national number is 52 percent," he says, "so you know Massachusetts is going to be higher than 52 percent."

Maine

Maine decriminalized marijuana possession back in the 1970s. Under current law, as amended in 2009, possessing less than 2.5 ounces is a civil violation, punishable by a fine of $350 to $600 for up to 1.25 ounces and $700 to $1,000 for more than that. A medical marijuana initiative passed in 1999 with 61 percent of the vote. In 2013 more than two-thirds of Portland voters backed an MPP-supported ballot initiative repealing all local (but not state) penalties for possessing up to 2.5 ounces. A similar initiative passed in South Portland last year.

"We looked at it as getting the voters and the media used to thinking and talking about marijuana in a very intense way," Kampia says. "We were just trying to get people used to thinking about marijuana so that when we go for the big one, it's not going to be considered alarming." In 2013 Public Policy Polling found that 48 percent of Maine voters supported legalization, while 39 percent were opposed and the rest were undecided. Mason Tvert, MPP's communications director, says he believes that is the most recent publicly available poll on the question.

The MPP-backed Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol submitted a Colorado-style legalization initiative to the Maine secretary of state on March 24, aiming for the 2016 ballot. Legalize Maine, a competing group that bridles at such out-of-state meddling, submitted its initiative in February. The campaign says "Mainers don't need a group from Washington, D.C., to dictate what's best for them."

Arizona

In Arizona, where voters approved medical marijuana by a razor-thin margin in 2010, the Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol is working on an initiative similar to Colorado's that includes a 15 percent sales tax. Kampia notes that Arizona currently has about 90 medical marijuana dispensaries and may eventually have as many as 126. "It all seems to be working well," he says. "The medical marijuana system that's currently operating is showing the people of Arizona that having some marijuana stores scattered around the state is really not causing any community problems."

A February poll by the Morrison Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University found that 45 percent of Arizona adults want to "make all marijuana use legal for those 18 years of age and older." A 2014 poll conducted by Scutari and Cieslak Public Relations found that 51 percent of Arizona voters supported legalization.

Which Will Win?

At this point (which is still quite early in the process), legalization looks likely in California, Nevada, and maybe Maine, less so in Ohio, Massachusetts, and Arizona. "The polling in Ohio, while better than what some people might expect, is not as good as in [other] states," Kampia says, "so they're taking a risk. It's their money, so the only downside for us is that if they lose, which is not guaranteed, it might change the national narrative for one year."

Not surprisingly, Kampia is more bullish on the states where MPP has decided to put its money. "We're financially invested in the big five states [voting on this issue] in 2016," he says. "We wouldn't be spending money if we didn't think we could win five out of five. But in terms of whether I think we would consider it to be a victory or not, three out of five would be considered a victory, and four out of five is probably the most likely scenario."

That seems overly optimistic to me, but what do I know? I did not expect the Colorado and Washington initiatives to win in 2012, especially not by such healthy margins, and I did not expect voters to approve all three legalization initiatives on the 2014 ballot either. I look forward to being pleasantly surprised again.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Which States Will Legalize Pot Next?."

Show Comments (2)