How Even a 'Well-Trained Narcotics Detection Dog' Can Be Wrong 84 Percent of the Time

In my column today, I note that the Supreme Court, ruling for the first time that a drug-detecting dog's alert is by itself enough to justify a vehicle search, discounted the relevance of a dog's track record in the field, saying its performance in "controlled testing environments" is a better measure of reliability. One problem with that position is that such tests are often so poorly designed that it's impossible to say whether the dog is detecting drugs or reacting to its handler's cues. But even well-designed, double-blind tests grossly exaggerate a dog's ability to provide probable cause for searches in real-world conditions. As University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill law professor Richard E. Myers explains in a 2006 George Mason Law Review article, the basic problem is that drugs are always present in the testing situation but rarely present in people's cars. So even a dog that is very good at finding drugs in a "controlled testing environment" will generate a lot of false positives when sniffing randomly selected cars. In fact, Myers says, it is easy to imagine how even a well-trained drug-detecting dog could generate many more false positives than true positives.

Myers asks us to consider a dog who performs well in testing, failing to alert in the presence of drugs just 5 percent of the time. Furthermore, when this dog does alert, it is wrong just 10 percent of the time. The latter number sounds like a solid basis for probable cause—which, according to the Supreme Court, requires a "fair probability" that evidence of a crime will be discovered. But if this dog works at a checkpoint where cars are stopped at random, and if 2 percent of cars contain drugs, he will alert erroneously much more often than he alerts correctly:

With a pretty good dog, but a largely innocent population, a dog alert will signal drugs only about sixteen percent of the time. The reason is this: Because the officer is stopping mostly innocent people, one has to be more concerned about the false positive error (alerting when there are no drugs). Because there are more cars without drugs in them, the gross number of searches that result from the error rate will be higher than the gross number of searches that result from correct alerts. Overall, there will be many more searches of innocent people than there will be searches of guilty people.

You can click through to see Myers' math, which is based on a Bayesian probability formula. The results depend, of course, on exactly how good the dog is and what percentage of cars actually are carrying drugs. But assuming the percentage is low, the basic point remains: Even the "well-trained narcotics detection dog" of the Supreme Court's imagination will be wrong in this situation much more often than he is right. Given this reality, you can start to see how actual police dogs, who perhaps are not quite as well-trained as the Court assumes, could be wrong more than nine times out of 10 when they alert to randomly stopped cars, as they were at roadblocks set up by Florida state police in 1984.

If we move away from random selection and consider cars that are examined by dogs based on some sort of suspicion that falls short of probable cause, the percentage carrying drugs presumably is higher than the rate for the general population of motorists. That helps explain why a 2011 Chicago Tribune analysis of data from suburban police departments found that vehicle searches justified by a dog's alert discovered drugs or drug paraphernalia 44 percent of the time—still not great, but a lot better than the 4 percent managed by those dogs in Florida. Myers argues, contrary to what the Supreme Court ruled last week, that a dog's alert by itself should never count as probable cause. If the chance of finding drugs is something like 16 percent, as in Myers' example, that does not qualify as a "fair probability." Still, Myers says, a dog's alert may justify a search when combined with other evidence:

Simply because the alert alone should not constitute probable cause does not mean that the dog's alert is not a critical piece of evidence that can combine with other evidence to constitute probable cause. Suppose instead that the police officer deploys the dog upon a suspicion, based on other factors, that suggests the presence of narcotics. If the officer has a pretty good nose of his own for narcotics dealers, then other studies on hit rates of police officers conducting searches based on factors that otherwise have been held to constitute probable cause suggest he may have a thirty percent chance of being right. In that case, the prior probability that the car contains drugs will significantly increase the importance of the detector dog's alert. Under those conditions, the Bayesian calculation, with a thirty percent prior probability and a ninety percent accurate dog, would result in a seventy-nine percent chance that there are drugs in the car—clearly probable cause.

Myers concludes that "requiring reasonable suspicion coupled with the dog sniff—whether it is found before the sniff or after—is a simple and practical safeguard for ensuring the presence of probable cause before conducting the search." Unfortunately, the Supreme Court's decision in Florida v. Harris seems to rule out this sensible, reality-based approach.

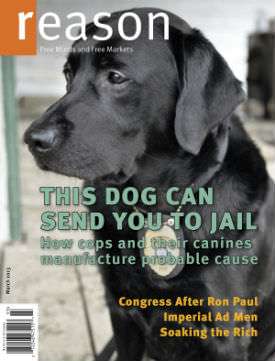

For more on how police dogs function as "search warrants on leashes," see my cover story in the March issue of Reason.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"Those dogs can smell anything. That's why you gotta kick em in the throat!"

Looks like err was wrong.

"The fry man is not excited to see us."

Not that the polygraph is valid, but it's a hell of a lot more valid than a drug dog's "alert." How the hell can one be barred from use under all circumstances but the other is PRESUMED valid unless proven otherwise by the DEFENDANT? [Usually the burden is on the party introducing the science/evidence.]

You can't even prove that the whole science behind it is bullshit--the court presumes that the science of drug dogs is 100% validated--rather you are only allowed to show that THIS particular dog isn't adequately trained.

How the hell would you even prove that to a court's satisfaction?

And if a drug dog alerts for pot (or whatever) and then they find something else illegal, how is that probable cause for the other thing? If they'd gotten a warrant, it would have been to search for pot, not search for everything.

Also, a polygraph prints out something that 3rd parties can review. No one can review an alert. (Or even verify it if there's no camera.)

Are we supposed to subpoena the prosecution's dog and take it to a neutral testing site to examine it?

How Even a 'Well-Trained Narcotics Detection Dog' Can Be Wrong 84 Percent of the Time:

"Hey, Bullet! Do you smell something? Of course you do Bullet! Good dog!"

That's how.

Look, there's an obvious solution here, replace dogs with horses. Horses aren't ass-kissers like dogs and the have a sense of smell that is at least within the ballpark of a dogs. And cops are already riding them around. Sure they may leave a smelly calling card in high school hallways, but that's a small price to pay to keep our children safe from the scourge of pot. Also, horses already eat grass, so any evidence found can be disposed of on the spot in a ecologically healthy manner.

This is win-win all the way around.

There's a reason the Clever Hans effect was named after a horse...

Don't you dare slay my beautiful hypothesis with ugly facts!

Maybe we need drug cats. Just don't try to smuggle catnip.

Cats would pretend to smell stuff anyways just to se your car get torn apart, because they're total dicks.

Why don't they just establish a precedent that "eeny meeny miney moe" is valid basis for reasonable suspicion?

Or drug detecting dousing rods.

I've been training gundogs as an avocation.

A while back, I was working with a very experienced trainer who does some radical things with dogs because he pays much more attention to the dog than most trainers, who just force the dog to "go through the motions" and call it a day (a red flag in itself, but others have made that point already).

We were working with my Vizsla, a dog I thought I knew pretty well. We were headed back to base camp after we'd had him find game birds in brush. The dog had been having a great time. He kept running around and sniffing, ran along the edge of a field, and suddenly locked up hard on point.

I said, "I think he's got another bird out there." The wise professor said, "Nope. He's lying. He just wants us to go out there with him some more." I didn't believe him. He said, "Well, we're the first people out in these fields today, and I can guarantee there are no birds out there. The dog already found everything we put out." I still questioned him, so he said, "Go find out!" and laughed.

So I did. I walked over to the dog, who had been furtively glancing over his shoulder at me. When I got within 10 yards or so, the dog just broke point and took off running around the field again, happy as a pig in shit.

The wise trainer was right! The dog FAKED A POINT, a beautiful point, for the sole purpose of drawing us back out in the field so he could hunt some more. I'd say that just about anyone who watched would have been fooled, as I was.

Cont'd:

Dogs are living things, with a sense of humor (rather crude I think), a sense of fun, emotions, and drives. A dog that learns that, when he signals "I smell pot!" that's when the fun happens, is entirely capable of independently and knowingly FAKING IT. Dogs get bored, as any dog owner knows! Drug-sniffing dogs know how to keep things from getting boring.

That's why a controlled test doesn't mean much. Give the dog plenty of stuff to find, and he/she will have a good time and be satisfied. Let the dog smell 1000 cars with no drugs, and the dog will get bored. Seriously.

It doesn't even require the intervention of a handler. The dog can deceive. They are predators, after all, and deception is part of their genes just as it is part of ours.

Really good point.

Why would we humans be the only animals that get bored and look for ways to break that? Or just do things for shits and giggles? These are self-aware animals not cyborgs we are talking about.

Like I said, I've seen it happen, and it was very, very clear when I experienced it. We're talking about a top-notch bird dog here, with a lot of hunting experience. There is NO WAY he really smelled birds there, and his behavior when I approached, showed that he didn't. He consciously faked a point so he could keep on enjoying himself.

56% of the time nothing was found. A dog alert would seem to indicate that it's more likely than not that there is NOTHING in the car. They could make a better case to search the non-alerted vehicles.

We need a better method of accountability for the supreme court. Their ruling is patently absurd.