The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

My New Brennan Center Article on Tyler v. Hennepin County and the Cross-Ideological Case for Stronger Judicial Protection for Constitutional Property Rights

The Tyler home equity theft case is just the tip of a much larger iceberg of property rights issues where stronger judicial protection can protect the interests of the poor and minorities, as well as promote the federalist values of localism and diversity.

The Brennan Center for Justice State Court Report (NYU) has published my new article on the Supreme Court's recent important takings decision in Tyler v. Hennepin County. Here's an excerpt:

Last week, the Supreme Court issued its decision in an important Takings Clause case that increased protections for property rights. Tyler v. Hennepin County addressed "home equity theft," a legal regime under which local governments can seize the entire value of a property in order to pay off a smaller delinquent property tax debt. The ruling has substantial implications for the relationship between state law and constitutional property rights. While states are free to protect property rights — and other rights — more than the federal Constitution requires, the latter sets a vital floor below which states must not fall.

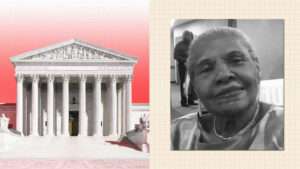

Geraldine Tyler, the plaintiff in the case, is a 94-year-old African American widow whose home was seized by Hennepin County, Minnesota, in 2015 after she couldn't pay off $15,000 in taxes, penalties, interest, and fees. After selling the home for $40,000, the county then kept the entire $40,000 for itself, as Minnesota law allows. Geraldine Tyler sued the county, arguing that the seizure of the surplus funds is a taking of private property requiring the payment of "just compensation" under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. While takings cases often split the Court along ideological lines, Tyler was unanimous….

Tyler… decisively repudiated the idea that states can avoid takings liability simply by redefining property rights through legislation. Chief Justice John Roberts's opinion for the Court holds that "state law is one important source [of property rights]. But state law cannot be the only source…."

The theory of state supremacy over the definition of property rights is one longstanding argument for judicial deference to states in takings cases. The Court was right to reject it…

Another standard rationale for deference to states on takings issues is the claim that state and local governments are best able to consider diverse local conditions affecting land-use issues. But this "diversity" rationale would justify gutting federal judicial protection for a wide range of constitutional rights….

Judicial protection for property rights actually promotes diversity and decentralization, rather than undermining it. By giving individual property owners greater control over their own land, judicial review allows a broader range of land uses and more local diversity than if states and localities retain unconstrained power to impose one-size-fits-all restrictions over large areas….

While the cross-ideological coalition in Tyler was unusual, home equity theft is just the tip of a much larger iceberg of situations where stronger judicial enforcement of property rights could help protect the poor, the politically weak, and minorities. The best example is exclusionary zoning, as regulatory restrictions on housing construction price millions of lower-income people out of areas where they could otherwise find greater opportunity….

The same applies to the cases like Berman v. Parker (1954), and Kelo v. City of New London (2005), which ruled that almost anything — including privately owned "economic development" — can qualify as a "public use" under the Fifth Amendment, allowing the government to seize property through the use of eminent domain. This ultra-broad definition of "public use" is at odds with the original meaning of the Fifth Amendment, and has enabled state and local governments to forcibly displace many thousands of primarily poor and minority residents….

Zoning and public use are far from the only issues where there is a compelling cross-ideological case for strengthening federal judicial protection for property rights. Others include asset forfeitures, inadequate compensation for owners of condemned property, and more…..

As with other constitutional rights, states remain free to provide greater protection for property rights than the federal Constitution requires…..

But states' ability to rise above the federal floor is not a justification for letting them fall below it. A variety of political pathologies often incentivize states and localities to under-protect constitutional rights — including property rights — especially those of the poor, minorities, and the politically weak. In such situations, federal judicial protection is vital. That's especially true where strong judicial review actually enhances the federalist virtues of decentralization and diversity.

NOTE: Geraldine Tyler is represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation, which is also my wife's employer. She, however, is not one of the attorneys working on the case.

Show Comments (9)