The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Justice Stevens Admits Error in the Kelo Case—but Also Doubles Down on the Bottom Line

In his recent memoir, he admits he seriously misinterpreted precedent in one of his most controversial decisions, but maintains he still got the result right.

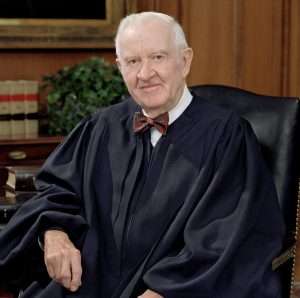

In his recently published memoir, The Making of a Justice: My First Ninety Four Years, retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens includes an extensive discussion of his majority opinion in Kelo v. City of New London (2005). The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment indicates that the government may only take private property for a "public use." In Kelo, a narrow 5-4 Supreme Court majority ruled that almost any potential public benefit qualifies as "public use," thereby permitting the City of New London to take fifteen residential properties for purposes of transfer to a new private owner in order to increase "economic development."

Stevens calls Kelo "the most unpopular opinion that I wrote during my more than thirty-four years on the Supreme Court. Indeed, I think it is the most unpopular opinion that any member of the Court wrote during that period." Kelo was indeed highly unpopular. Polls showed that over 80 percent of the public opposed the decision, an outcry that cut across conventional ideological and partisan divisions. Some 45 states enacted eminent domain reform laws in response. The unpopularity of the ruling does not, however, prove that it was wrong. What does make it wrong are the serious errors in Justice Stevens' majority opinion.

In his memoir, Stevens fortrightly acknowledges one of them: serious misinterpretation of relevant precedent. Stevens' majority opinion in Kelo relies heavily on the claim that its very broad definition of "public use" is backed by "more than a century" of precedent. That assertion is false. The nineteenth and early-twentieth-century cases cited by Justice Stevens as support for extreme judicial deference under the Public Use Clause in fact addressed public use challenges under the "Lochner-era" doctrine of "substantive" due process applying the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. During that period, the Supreme Court had not yet recognized that the Fifth Amendment applied against state governments. Thus, the only way for property owners to challenge a state or local government taking in federal court was under the Due Process Clause.

Stevens now acknowledges that these were not Public Use Clause cases, and describes his reliance on them as a "somewhat embarrassing to acknowledge" error. He generously cites me as a "scholarly commentator" who "caught this issue shortly after we decided Kelo," in an article I published in 2007. These concessions expand on similar admissions Stevens made in a 2011 speech on Kelo, which I discussed in my book about the case (which Stevens, in turn, cites in his memoir).

Stevens deserves great credit for publicly acknowledging a significant mistake in one of his best-known opinions. Few judges are so openly honest and self-critical about their errors. It is also very impressive that Stevens is still writing books and otherwise contributing to public debate at the age of 99. We should all have such vigor and work ethic!

As I noted in my book, this one mistake does not by itself prove that Kelo was wrongly decided. The decision was still backed by more recent precedent, most notably the Court's 1954 decision in Berman v. Parker, which also held that a public use can be almost anything the government says it is, thereby upholding an urban renewal project that used eminent domain to forcibly displace thousands of poor African-Americans. But a poorly reasoned ruling decided during the mid-twentieth century nadir of judicial respect for constitutional property rights doesn't carry the same weight as "more than a century" of precedent endorsed by justices representing different time periods and judicial philosophies. The ultra-broad definition of "public use" endorsed by the Court in Kelo and Berman is also at odds with both the original meaning of the term, and leading variants of "living constitutionalism."

Despite this notable concession, Stevens continues to believe that Kelo was rightly decided. But his new rationale for the decision is completely different from the one offered in his majority opinion for the Court. He now argues that the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment does not constrain the purposes for which the government can condemn property, at all.

This rationale (previously advanced by a few legal scholars) is actually much more dubious than the broad definition of "public use" Stevens advocated in the Kelo decision. Among other things, it really is at odds with not just one century of judicial precedent, but two. While there is longstanding disagreement between advocates of broad and narrow definitions of public use, two centuries of state and federal judicial precedent hold that "public use" imposes at least some constraint on the reasons for which government may condemn private property.

In my view, textual and historical evidence provides stronger support for the narrow view, under which a public use exists only if the condemned property is transferred to government ownership (as in the case of public infrastructure such as roads and bridges) or to a private owner that is legally required to serve the entire public, such as a public utility or common carrier. But even advocates of the broad definition hold that the Fifth Amendment constrains the range of permissible takings at least to some small degree.

They recognize that it bars condemnations where there is no chance of any public benefit, and perhaps also those where the official public purpose is just a "pretext" for a scheme to benefit a politically influential private party. Stevens himself endorsed the latter constraint in his Kelo majority opinion, as did Justice Anthony Kennedy in his influential concurring opinion. Lower courts have since struggled to figure out exactly what counts as a pretextual taking under their reasoning. I offer additional criticisms of Stevens' radical new justification for Kelo in chapter 2 of my book about the case.

Stevens does indicate that there might be some constraints on eminent domain imposed by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. But if so, they are very minimal, since in his view they do not preclude even the egregious taking in Kelo itself, which was heavily influenced by interest-group lobbying and resulted in a badly botched "development" project. To this day, the site of the condemned property lies empty, used only by a colony of feral cats who have taken up residence there.

Stevens' reliance on the Due Process Clause as the only substantive constraint on the purposes for which government may use eminent domain is also in tension with his claim (also made in his memoir) that critics of the Kelo decision are analogous to defenders of the Court's much-despised ruling in Lochner v. New York (1905), which held that the Due Process Clause protects freedom of contract and forbids maximum hours laws for bakers. The standard critique of Lochner is that the Court was wrong to use the Due Process Clause to protect "substantive" rights (as opposed to purely procedural ones) and that this error is particularly inappropriate in the case of "economic" rights. Ironically, Stevens' new view is that the Due Process Clause does indeed provide protection for substantive "economic" property rights (albeit only weak protection). By contrast, we who oppose the Kelo decision argue that role should be played by the public use component of the Takings Clause, which is both explicitly substantive and specifically intended to restrict the seizure of private property by the state.

I believe that Lochner does not deserve most of its terrible reputation, and that accusations of "Lochnerism" are routinely overused by both liberal and conservative justices. In this instance, however, Justice Stevens is "Lochnerizing" to a far greater extent than opponents of the Kelo decision. He would extend Lochner-like reasoning to a new area, from which the latter would prefer to exclude it.

In his memoir, Stevens also points out that the Court has never explicitly ruled that the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment is "incorporated" against state governments. He is absolutely right about that. At some point in the early to mid-twentieth century, the Court began to simply assume (wrongly) that the Clause had already been incorporated in the Lochner era, and thus should apply to state governments. Stevens' mistake in the Kelo opinion has its roots in that longstanding assumption, though (as Stevens now recognizes) the falsity of that assumption is easily established simply by reading the decisions in question (which explicitly indicate that the Fifth Amendment was not considered applicable to the states at the time).

It is not clear to me whether Stevens now thinks that the Takings Clause should not apply to state governments. If so, it would be a major anomaly in an era when nearly all the rest of the Bill of Rights has been ruled applicable against states and localities, usually with the support of both liberal and conservative justices. Ending incorporation of the Clause would also require overruling many Supreme Court rulings, which did apply it to the states, including Kelo itself.

Stevens' admission of error in a major part of his Kelo opinion does not by itself prove that the decision should be overruled. But it does strengthen the case for the Court to reexamine the ruling to determine whether it should indeed be reversed or at least pared back. As I explain here and more fully in the conclusion of my book, there are several possible ways to limit or overrule Kelo, depending on how far the justices want to go.

I also explain there why Kelo fits the Supreme Court's established standards for identifying constitutional precedents that should be reversed. Those standards include whether the decision was "well reasoned" and whether it has been subject to "substantial and continuing criticism." Few major Supreme Court rulings have been subject to as much "substantial and continuing criticism" as Kelo, and fewer still are based on reasoning that even the justice who authored the decision now in large part rejects.

Perhaps Stevens' admirably honest retrospective assessment of Kelo will hasten the day that the case is overruled. If so, it could turn out to be one of the last great public services of his distinguished career.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Whatever else, a "public use" is, it seems to me, it must be an actual use of the property - not a transfer to a private party - by the public, which is to say the government.

If anything at all counts, why is the phrase there at all?

It sounds better than "steal."

"without just compensation"

If they have to pay market value - and they do - it's not "theft".

It's not Rothbardian libertopian property rights, but it ain't theft.

(And under Kelo it's far too broad a power, but still not theft, properly.)

It's there so liberal government can steal property from citizens. For "public use", being whatever "public use" the liberal says it is.

I don't think eminent domain is particularly popular among liberals, Kelo notwithstanding.

Lots of the abuses have been in favor of developers, at the expense of not-wealthy homeowners.

Here is some information about one such developer.

So get off your high horse about what your cartoon liberals want.

Oh please, a 5-4 Supreme Court decision, where the liberal justices lined up on one side, and the conservatives on the other? It's a classic liberal decision, only to be "regretted" later

Oh please.

That the liberal Justices voted the way they did doesn't prove anything about what all liberals think. The Kelo decision was widely criticized all around.

Here is the NAACP, for example, in a Congressional hearing.

it should come as no surprise that the NAACP was very disappointed by the Kelo decision. In fact, we were one of several groups to file an Amicus Brief with the Supreme Court in support of the New London, Connecticut homeowners.

From a VC post by Todd Zywicki shortly after the decision:

Even Congress's "lone self-described socialist, Rep. Bernard Sanders of Vermont" doesn't like Kelo:

I disagree with the Supreme Court's decision in Kelo v. New London," Mr. Sanders said. "I believe that the result of this decision will be that working families and poor people will see their property turned over to corporate interests and wealthy developers."

Rep. Maxine Waters, "California Democrat and member of the Congressional Black Caucus, said she is 'outraged' by the decision. 'It's the most un-American thing that can be done.'"

And when is the last time those two agreed with Tom DeLay?

"The Supreme Court voted last week to undo private property rights and to empower governments to kick people out of their homes and give them to someone else because they feel like it," said House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, Texas Republican. "No court that denies property rights will long respect and recognize other basic human rights."

The Washington Post describes the legislation, co-sponsored by conservative James Sensenbrenner and liberal John Conyers in its story, curiously titled "House Votes To Undercut High Court On Property"

The House measure, which passed 231 to 189, would deny federal funds to any city or state project that used eminent domain to force people to sell their property to make way for a profit-making project such as a hotel or mall. Historically, eminent domain has been used mainly for public purposes such as highways or airports.

Bernie Sanders, Maxine Waters, John Conyers.

So STFU with your "All bad things are the liberals' fault BS."

In this case it was the liberals fault.

"The Kelo Decision was widely criticized all around"

Oh really?

The New York Times: "a welcome vindication of cities' ability to act in the public interest."

The Washington Post: "[t]he court's decision was correct. . . . New London's plan, whatever its flaws, is intended to help develop a city that has been in economic decline for many years."

I wonder what the Post and NYT Editorial boards have in common....

It was widely, not universally, criticized by liberals. There was no unanimity.

Uh huh...but when it cam the to fixing it, it wasn't the blue states.

California (where thousands of properties have been "condemned" with eminent domain for "blight"), New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, New Jersey...all scored D or lower for laws to protect against eminent domain abuse.

Alabama, Arizona, Florida, North Dakota, etc...all got a B or above. Even Texas got a C-

What about Arkansas? Mississippi? Oklahoma?

What about them? Do they have a history of abusing eminent domain? Or not..really. Or did they pass Constitutional Amendments banning this type of aggressive eminent domain abuse (MS did...)

Mississippi's eminent domain amendment excludes drainage and levee facilities and usage, roads and bridges, flood control, toll roads (<--this is private use), energy, etc. But you're on the hunt! What about Oklahoma and Arkansas?

Listen, Eminent domain is necessary and needed in some situations. The law exists for a reason. Levees are an excellent example.

Where it's not needed is when a "liberal" democratic government decides to strip property from people to give it to other, more well-connected people, for "economic" development or because "They'll build a bigger, more expensive house which we can tax more". And that's what's surprisingly common in NJ, NY, and CA.

Are toll roads, in your view?

"Where it’s not needed is when a “liberal”..."

Oh, I see now.

“That the liberal Justices voted the way they did doesn’t prove anything about what all liberals think.”

No. But what it does prove is that the term “liberal” has become so chameleon-like in usage that it has ceased to have any meaning at all. The so-called “liberal” wing of the Court has abandoned any pretense of being truly liberal. Yes, they ardently defend the “liberties” which they like, such as the right to obtain an abortion on demand, the right to gay marriage, and the right to race-based and gender-based preferences (Justice Sotomayor’s dissent in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, joined by Ginsburg, is a hilariously insipid defense of Orwellian “equality”, in which some pigs are more equal than others). But they are often openly hostile to other civil rights, even those found in the Constitution, like Second Amendment rights and the right to free exercise of any religious belief which dares disapprove of abortion rights or full equality of gays. They are especially hostile to any rights characterized as property rights, consigning those rights to second class status. A classical liberal was opposed to the interference with personal liberty by an over-reaching government, but modern “liberalism”, a/k/a “progressivism” positively applauds government intervention. Modern liberalism, on the Court at least and far more often than not in Congress as well, is mostly authoritarian statism, and Kelo was a prime example of that. The fact that some, even many, on the left will occasionally (but not nearly often enough) revert to truly liberal principles when the light finally goes off in their heads that authoritarian statism will inevitably be used to disadvantage the politically weak is hardly a vigorous defense of modern liberalism.

"No. But what it does prove is that the term “liberal” has become so chameleon-like in usage that it has ceased to have any meaning at all."

For a substantial minority of the country, "liberal" means "anything we disapprove of".

It's taking a government power and greatly expanding the definition. That's also the definition of modern liberals views of the constitution along with a number of so called conservatives.

Leftist please, not "liberal."

Eminent domain isn't popular among Americans. It's one of those things that government and corporations like, but most actual people think is horrible.

"most actual people think is horrible."

Depends on what's being built, and when, and why.

Give them a reason to want the project to be done, and Americans of almost all types will turn and think it's great that the project is going to get done.

I mean, he's making straw-liberals, for sure.

But they like Eminent Domain pretty well for their pet projects, just as conservatives have been known to for theirs.

The main difference is the left has a lot more pet projects.

(Railways! Housing developments! Urban renewal! Parks! Theaters! Government everything!

vs.

Er ... military bases, the occasional jail, and rarely either in town?)

That, there.

If the phrase means nothing, it's superfluous. But none of the other text in any of the amendments is superflous. (Those closest I can think of is the preliminary clause to the Second Amendment, which is of no practical legal bearing [on the grounds that even if we accept Miller's reasoning, there is almost no arm that has no military utility].)

It was plainly meant to constrain the Federal government from taking land for anything other than public purposes, in the form of the State doing something with it.

It's almost impossible to interpret it in any other way.

"It was plainly meant..."

But what you go on to say is different from what the Constitution says. The Constitution says that private property can't be taken without paying for it. It doesn't really say anything about what the gov't can do with it after it's paid for.

I think a "taking for a public purpose" is distinguished from a seizure of contraband. If the cops take pull you over and take your drugs, they don't have to pay you for them. But if they take your land to build a road, they do. Under this interpretation, a broad meaning of "for public use" is to the benefit of private citizens.

In Kelo the intended use of the land never happened yet the state government was allowed to condemn the land merely by saying what they intended to do. Given that, as long as the state government says they intend to use the land for public use then they can take the property.

It doesn’t seem that the constitutional language puts any constraint on government condemnation.

I'm not quite so sure about that, actually I'm quite sure a transfer does not void the public use.

After all a more literal definition of "public use" is that the public uses the property. So "public use" has always encompassed condemning property for a railroad, or a turnpike, even if privately owned and operated. It's use for electrical

transmission lines whether pylons or buried cable or oil, natural gas, or water pipelines has also been relatively uncontroversial even if owned by a private or publicly traded corporation.

Wikipedia says that the Takings Clause was incorporated in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago, 166 U.S. 226 (1897).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incorporation_of_the_Bill_of_Rights

Are you saying Wikipedia is wrong?

Yes, whoever wrote the Wikipedia article made the same mistake Justice Stevens did - they quoted Justice Harlan saying the Due Process clause requires payment for seizures, and ignores the fact that the majority used Due Process in the 14th amendment explicitly rather than the 5th amendment.

Back then the Supreme Court would say that none of the Bill of Rights applied to the States, but many times would rule that a right that happened to be in the Bill of Rights did apply to the States to the extent that right was "fundamental" to liberty. By the '60s, the Court rejected that silly distinction. So while Robert Beckman is technically right, he is substantively wrong.

" . . nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation"

Stevens: since this was a taking for private use, the constitution does not require compensation, just or otherwise.

I worked on a substantial number of condemnation and "takings" cases over the years, almost all of which were pre-Kelo. I have a hard time figuring out what the PRACTICAL difference is between the Berman rule and the Kelo rule. What seems to me to be really important is that Berman was pretty well accepted by the public, whereas Kelo was and is widely regarded as an awful decision, one that we can reasonably hope will be overruled one of these days. In other words, the PUBLIC'S understanding of the 5th Amendment has changed for the better, and if Mr. Dooley is correct, the Court may in due course change its mind, too.

[…] from Law https://reason.com/2019/06/08/justice-stevens-admits-error-in-the-kelo-case-but-also-doubles-down-on… […]

Justice Stevens is an ass. His dissent in District of Columbia v. Keller, in which he refused to follow the text of the Second Amendment (“the right of the PEOPLE . . .”) to find an individual right, and his downright silly, if not bad faith, mischaracterization of Miller v. United States, prove as much. I’m just not interested in his opinions, on Kelo, Heller, or otherwise. My default position is that if Stevens makes a claim on a legal position, he is almost certainly wrong.

It is also very

impressivedisturbing that Stevens is still writing books and otherwisecontributing todebasing public debate at the age of 99.He reads the Second Amendment as altered in the way he would like to amend it (https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-five-extra-words-that-can-fix-the-second-amendment/2014/04/11/f8a19578-b8fa-11e3-96ae-f2c36d2b1245_story.html):

because he, apparently, thinks he's smarter than the Founders and that they inadvertently left out some words.He also slyly misrepresents United States v. Miller when he states:

when the decision actually states [emphasis added]:

So the court merely said that absent evidence that a short barreled shotgun does has a use in a militia, the court would not assume that it did, in fact, have such a use (it now seems rather quaint that the court wouldn't just make up what they wanted to in order to reach a conclusion).Of course, Stevens fails to mention that neither Miller or his lawyer appeared or filed a brief in the case because the lawyer was not being compensated and was apparently bored with the case. So, it's not surprising that such evidence was not presented.He also glosses over the obvious implication of Miller that the Second Amendment would protect ownership and 'bearing' of any weapon that did have a use in a properly functioning (i.e., effective) militia (i.e., a weapon appropriate to repel or disable an well equipped invading force) -- including, obviously, fully automatic weapons and true assault weapons that every military has access to.

"neither Miller or his lawyer appeared or filed a brief in the case because the lawyer was not being compensated and was apparently bored with the case. "

That Miller was already dead might have played a role in this, too.

IIRC, Miller's body was found about one week after the Supreme Court hearing and before their decision was issued. Has it been established he actually died before the hearing?

US v Miller was decided May 15th, it was remanded for a determination if sawn off shotguns had military utility. The remand was officially transmitted to the lower court on June 14th, he was reported dead on June 17th, so the determination never occurred.

I don't know if he was dead at the time of the Supreme court ruling, but in theory at least, if he'd been around and represented during the remand, his counsel could have produced the evidence of sawn off shotguns' military utility, and the lower court could have confirmed their initial ruling in his favor, consistent with the Supreme court's directions.

“I fucked up but I’m still right”.

More like, "The founders fucked up, but I'm still right."

He's just doubling down on his approach to the Constitution while on the Court: His policy preferences drive the Constitution's meaning.

Bingo. Ginsberg is another in the same role.

"His policy preferences drive the Constitution’s meaning."

"Bingo. Ginsberg is another in the same role."

That is a fairly common problem with Ginsburg

Encino motors - policy preference service advisors should get OT, therefore -

ACA concurrence - ACA is good public policy, therefore compelled commerce is constitutional

Lilly Ledbetter - Statute of limitations is bad policy, therefore expansion of statutory text of applicable statute of limitations is good.

Frequently her opinions are policy preference argruments disquised as constitutional analysis.

Ginsberg isn't making policy arguments in those opinions, though, Joe.

"Ginsberg isn’t making policy arguments in those opinions, though, Joe."

Sacastro - you obviously havent read those opinions -

Her first 4-5 pages of the aca concurrence was a policy argument.

Stevens: "The Supreme Court knows what is best for society. Government knows how property should best be used. Thus, people must do what the government tells them to do."

SCOTUS declining to tell the people what they can and can't do through their elected representatives is not "know[ing] what is best for society". It's the opposite. If you don't want SCOTUS involved in decisions about what is in the best interests of society, you should embrace decisions like Kelo.

I don't want anyone involved in decisions about what is in the best interests of society for two reasons. One, those decisions carry the force of law compelling individuals to obey or else live in cages. Two, there is no such thing as the "best interests of society" apart from the interests common to all individuals - life, liberty and property.

In Kelo, SCOTUS didn't tell anybody what to do.

SCOTUS shouldn't tell state and local officials what's best and how to implement it, unless of course their implementation is constrained by the constitution, or applicable federal law.

Local officials would run roughshod over the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th amendments if allowed. They might even start quartering troops if they thought they could get away with it.

These are the same people who say changing values in The People change the meaning of the Constitution.

Two interpretations: it's about freedom and The People. Or, it's about expanding government power to secure more money to buy votes with.

Hmmmm, the latter, like General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, continues to pass every test thrown at it.

"Two interpretations: it’s about freedom and The People. Or, it’s about expanding government power to secure more money to buy votes with."

Meh. The federal Constitution lets the state and local governments take property for "public use" with an really broad definition of "public use". If you want a more limited meaning for "public use", write it into your state constitution or city charter. I don't own property in New Haven, Connecticut or any other part of Connecticut. So let the people there let their government take property to do whatever public use, or let the people there restrict their government's ability to take property to do whatever. Either way, it's none of my business.

" The federal Constitution lets the state and local governments take property for “public use” with an really broad definition of “public use”."

No, the "really broad definition" is exactly the mistaken ruling we're discussing here.

Dipwad, the "mistaken ruling" is the one that got 5 votes, and thus has force of law.

Well, duh: That's what made it a mistaken ruling,, rather than a mistaken "dissent".

Either way, mistaken, but as a ruling the mistake has teeth.

It has exactly the effect I described.

To which you said "No".

I thought I agreed with Somin about Kelo, but he shows with this OP that we differ a bit. Somin apparently wants to ground the takings clause in some notion of the sanctity of private property. I don't see why that is necessary. It is private property, it doesn't need also to be sacrosanct. Just keep the focus on limiting eminent domain to actual public use, which Somin seems to define adequately. That will get the job done without unneeded implication of penumbral constitutional rights residing in property.

So as long as the property is used for a public use, no compensation need be paid?

If not, how do you actually differ from Somin’s position?

I don't think Lathrop goes that far, because it would completely ignore the text of the 5th amendment: "nor be deprived of ... property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation."

He is just uncomfortable with the concept that people own things and the government can't interfere with the rights of ownership. Perhaps he is thinking of the Oregon case where it was considered a taking where the government insisted one landowner dedicate a portion of his land to a public bike path in exchange for rights to develop the rest, and a similar case in Florida. I think his preferred outcome is the government has the right to control your land as long as they preserve your right to pay the taxes on it.

Or you could content yourself with the truth, Kazinski, which is that you have no idea what my positions are on private property rights.

I think that it is deep flaw in our system of government that citizens may be forced to read centuries of opinions to find out what the law really says. Worse when courts take centuries to clarify unclear phrases.

Good post. Very educational.

We should have the right to have direct online access to an authoritative statement of the law in plain language. Reliance on that document should be a legally binding safe harbor for all citizens. Such reliance should be non-refutable -- as in the government claims that the online document incorrectly states the law. If a citizen is accused of misunderstanding the plain language, it should be left up to a jury.

It would need constant editing to reflect the thinking of all three branches. For example, in addition to opinions, SCOTUS would also produce a revision to that online document (e.g. strike out this and insert that). District courts do that same, but the revision is tagged to apply only to the district. The opinion is for the benefit of lawyers, the online document is for citizens.

It would need the ability to view according to location, and to applicable date. It could make full use of hyperlinks to make navigation and reading easier. For example, in the case of the phrase "public use", it could link to a more elaborate definition of the term.

Yeah yeah, there would be endless arguments in how to translate law into plain language, but it is worth the effort.

IMO, to not have that violates the rule of law. The technology is ubiquitous in today's world. Let's make use of it.

No. While your idea may be clearer and easier to follow it would also enshrine clearly wrong decisions like Dred Scot, Kelo, Plessy, Wickard, and even barely plausible decisions like Miller which were misinterpreted beyond all reasonable bounds into a complete negation of clearly stated constitutional rights.

It's better to leave the Constitution itself as the ultimate and best reference of the law, so it's easier to return to it when the governments and courts stray.

"enshrine clearly wrong decisions like"

At one point in time those wrong decisions were the law of the land. Without examples of doing it wrong, we rob incentives for doing it right.

Would you expunge slavery and the Civil War from history to avoid enshrining them?

Having spent a career writing software requirements, this is harder than you might imagine - particularly keeping up with updates.

I see two levels here. The first level is difficult but achievable by providing the current law in a linked, keyword searchable, geo-sensitive, time-sensitive format (e.g. property law as it applies to 1313 Mockingbird Lane in Hollywood, CA in 1964). The second level of everyone actually being able to interpret it is too horrific to even contemplate. Lawyers have no incentive to put themselves out of a job.

"age of 99. We should all have such vigor and work ethic!"

Who believes a 99 year old could write a book? Or even read one.

"but maintains he still got the result right."

Stevens also believes the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare so his delusions are long standing.

Oh, come on! I had an aunt who died at the age of 103. I'm pretty sure she could have written a book at only 99, and was certainly reading them until that heart attack.

"In his memoir, Stevens fortrightly acknowledges one of them: serious misinterpretation of relevant precedent."

You would think that at the Supreme court Level, a justice wouldnt make that kind of mistake, or at least one of his clerks would have corrected his mistake,

Who's to say what his clerks told him?

Maybe they all found the right analysis, and Justice Screams at Clouds overruled them.

Give me a break, his clerk obviously screwed up.

I have to say I am somewhat closer to his new interpretation, though politically I hate that. Admittedly I haven't researched founding era documents so this is based purely on the text. But the text to me doesn't read as a limitation on the reason for taking

That doesn't read as "public use" putting a limitation. It reads more as recognizing a previous limitation. The way I read it as making sure that simply talking about taking runs the risk of an interpretation of enlarging the powers beyond what is authorized. That is "public use" recognizes a limitation that was already on it, that being the Section 1 Article 8 powers (and other powers given in the Constitution). That is being used to implement its limited powers is limited to public use, because those powers constitute a public use. This also fits in with the rest of the BoR as not creating powers but limiting the use. But if "public use" is read as a limitation, which is not natural under the text, it also means that pre-BOR there wasn't this limitation. They could take for non public uses. This, though, doesn't make sense as much of the dispute of the BoR was not that these are rights, but whether they were needed. The Anti-federalists said yes, the Federalists said no because they didn't have the power to violate them in the first place (this is why the Ninth and Tenth were needed).

This was reasonable at the time since the BoR only applied to the federal government which had limited powers (and those powers were actually read as limited unlike today). The difficulty is that in applying it to State government which has the police power they didn't really have an inbuilt limitation to only have powers that constitute "public use." So we are left with either inventing one or keeping "public use" to be what it was, if it is otherwise in the power of the government it is a public use. I don't think the judiciary has the authority to do the former which leaves the latter.

As I said at the start, I hate what that ultimately means. And I would absolutely support a constitutional amendment to put on the narrow public use reading as a limitation. But I can't say that is how I currently interpret it. Again, though, with the caveat of not read founding error documents on it.

"In his recent memoir, he admits he seriously misinterpreted precedent in one of his most controversial decisions, but maintains he still got the result right."

Of course. Our Leftist judicial authoritarians rationalize backwards from the "right result".

Being wrong on their rationalization has no effect on the rightness of what they were rationalizing for.

If I'm not mistaken, Brennan admitted precisely this in a speech after he retired.

Stevens proposed 2A amendment where he adds " when serving in the Militia" is basically his admission that his dissent in Heller was wrong.

I don't agree with his dissent, but this is just false. The amendment is to change what the Court said it said, not what it does say. Whether the Court was correct has no relevance anymore. Just like any other amendment.

Uh no, his dissent in Heller is the perfect strict constructionist interpretation of the 2A. Now his McDonald dissent is the best of all of the opinions except in the end his partisan bias undermined his analysis.

The McDonald majority opinion actually undermines Heller because incorporation should not have been necessary based on Heller which in which “militia” referred to all citizens and “free state” referred to nation.

His dissent in Heller is a perfect mockery of a strict constructionist interpretation of the 2nd amendment. He observed the general form of the reasoning, while going hilariously wrong on the sources he used.

And, in Heller, "militia" did not refer to all citizens, (But rather, all citizens capable of military service.) but this is somewhat beside the point, since the right is a right of the people, not the militia. Incorporation was still necessary, because identifying who has a right does not establish what levels of government that right is in regards to. Which is the whole point of incorporation: Who is bound by, rather than entitled to, a right.

Wrong, because pursuant Scalia’s Heller opinion incorporation is not necessary...and yet a few years later the conservative justices inexplicably applied incorporation doctrine to a right which explicitly relates to all citizens in America!?!

I'm looking at Scalia's Heller opinion right at this moment.

Subtitle, pg 48: "23 With respect to Cruikshank’s continuing validity on incorporation, a question not presented by this case,...Our later decisions in Presser v. Illinois, 116 U. S. 252,

265 (1886) and Miller v. Texas, 153 U. S. 535, 538 (1894), reaffirmed that the Second Amendment applies only to the Federal Government."

You are free to claim that Scalia's reasoning made incorporation unnecessary. He didn't agree with you.

Except Scalia was very clear—that 2A was never meant to only apply to the federal government so incorporation was not necessary. So Cruikshank was wrong about the BoR only applying to the federal government because the 2A applies to all citizens in America.

The view that the 2A says, or should say, that the military can't restrict when and where it's members are armed strikes me as very strange.

Militia is different than the military.

True, though not relevant.

The military contains people who have voluntarily waived some of their rights. This is explained to recruits at basic training. As an American, you have rights; as an enlistee, some of them are temporarily suspended. The fourth amendment works differently on base than off, for example.

The 2A has nothing to do with the military. The 2A is a federalism provision that prevents the feds from disarming the state militias. As Cruikshank points out—we have a RKBA and it has nothing to do with the 2A.

"The 2A has nothing to do with the military."

Incorrect. Members of the military are citizens of the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction of the federal government.

Ok, the 2nd amendment has to do with the military in the sense that the military is composed almost entirely of citizens,, and the 2nd amendment has to do with the rights of citizens.

So it's got as much to do with the military as freedom of speech, or the right to jury trial.

People in the military aren't guaranteed a right to a jury trial.

It's not quite that stupid. It's more a matter of nobody ELSE being able to restrict somebody from being armed when and where the military says they should be.

Still nothing anybody would have described as a "right", though.

[…] If you haven’t done so already you might want to check out Professor Ilya Somin’s review of Justice Steven’s latest autobiographical book in which he has some more to say about his intellectual misadventure in authoring the Kelo majority opinion. It’s available on the Reason magazine post. See https://reason.com/2019/06/08/justice-stevens-admits-error-in-the-kelo-case-but-also-doubles-down-on… […]

Meh, Florida has attempted to limit eminent domain and it unfortunately has produced some pretty bad results—Marlins Ballpark was the direct result of the city having few options to acquire land to build a new ballpark. So instead of one person getting ripped off by the municipal government an entire city got ripped off. Nice try though.

In just what way is a ball park constructed for the use of a privately owned major league team, for the benefit of its owners, a “public use”?

IMHO, eminent domain should NEVER be used to build such private edifices as football stadia, baseball parks, or parking garages for Atlantic City casinos. If the developers want to build such projects, let them pay enough to get existing property owners to voluntarily transfer the property.

I agree with you, Dan.

Me too.

So you oppose rye city of Houston taxing its citizens to pay for a ballpark for the billionaire Drayton McLane...and then a few years later McLane pays out of his own pocket to build a football stadium for Baylor University? Why would you oppose something as convoluted as Houston taxpayers paying for a football stadium in Waco Texas?

George W Bush used eminent domain to build the Texas Rangers ballpark in Arlington and despite foolishly building an outdoor ballpark for a summer sport in Dallas the people of Arlington continue to support more taxes to build sports stadiums including a new ballpark to replace Bush’s folly. Contrast that with the law passed in Florida when Jeb was governor that resulted in the inability of city of Miami to find suitable land for the Marlins to build a stadium and the city suffers to this day because he that law handcuffs community leaders.

“and the city suffers to this day because he that law handcuffs community leaders.”

The city SUFFERS from the fact that so-called “community leaders” (i.e., politicians who have received sufficient campaign contributions to induce them to steal property from private citizens for the benefit of their cronies) are handcuffed by an inability to steal? I’m crying crocodile tears for those poor corrupt “community leaders”!

So George W Bush stole “land” from someone in Arlington and the Rangers and Bush and that particular sports district are popular with Texans. In Miami nobody stole from anyone and taxpayers got a raw deal and no one is happy.

Yes, the Rangers stole the land, and everyone who did NOT get their property stolen from them is happy about the outcome. What is your point? That theft by individuals is morally wrong, but becomes morally right when a majority of citizens deputizes some politicians to carry out the theft on their behalf?

The city should have simply changed the zoning to put a dog poo dump next to the a-hole who refused to sell.

Holy fuck you're an idiot, Cummington.

Trump tried to force an elderly woman out of her home with eminent domain. Bush successfully stole someone’s land to build his “Oven in Arlington”. But you were so brave to post on a comment board to that Souter is a poop head and we should use eminent domain to take his cabin!” You are such a brave and principled conservative activist! 😉

I think the problem is government-paid-for sports stadiums, not... whatever it is... that you think is the problem.

Says the commenter sticking by his vote for George W Bush.

"So instead of one person getting ripped off by the municipal government an entire city got ripped off. Nice try though."

But, that's exactly the way it's supposed to be: Government does stuff for the general welfare, and the general population is supposed to both benefit AND pay for it. "One person getting ripped off" is exactly what the takings clause was there to prohibit.

I'm one of the unpopular 20% who doesn't see anything wrong with Kelo. If you don't want your state or local government to be able to do that, put something in your state constitution or local charter that says they can't do that, instead of relying on vague wording in the federal Constitution that can be read to allow it. Then, vote for people who won't do it, instead of voting for people who will.

Got it.

Vote for solid conservatives, every time, rather than liberals who believe in the power of the state, and will look to steal your property for others.

Is it any surprise that Kelo was in New London, in Connecticut, rather than in a place with strong property rights, like Texas?

If you imagine this to be a partisan issue, then eventually you will be horribly surprised. "Solid conservatives" will use the power of the government to their advantage, if and when they can, with about the same gleeful abandon as the liberals do. If your property is in their way, guess what's going to happen?

Right now, the "solid conservatives" are SUPPORTING the President's ability to seize property to build his big, beautiful wall.

You'd think eminent domain wouldn't be needed. After all, Mexico is going to pay, so why not just give the landowners whatever price they want?

Maybe Trump is just addicted to eminent domain takings, based on his history.

Keep telling yourself that...even if it's not true. See, Connecticut has had multiple bills proposed, all by the state GOP, to limit this type of abuse. And for some reason, they keep dying in the Democratic controlled CT legislature. Hmm... Democrats SAY they don't like it. But when it comes to action, well... let's not be too hasty.

"Keep telling yourself that…even if it’s not true."

I keep telling myself that because it IS true. Partisans have such a distorted view of reality...

"What? OUR guys would NEVER..."

You do have a distorted view of reality, it's true. Look up the cases of eminent domain abuse, and look what they generally all have in common. An over-reaching, liberal government that believes "government knows best." Those are just facts.

Your theory that not looking through your partisan goggles gives non-partisans a distorted view of reality, the only possible reaction is to laugh at you.

Was that the response you were looking for?

Kelo was right! A great moment in American history, SCOTUS rejects a power grab and the states take up the issue directly through legislation.

Public Use vs Public Benefit. It seems to me that Public Use is a fairly simple and straight forward concept to determine. If might be possible to think of scenarios where Public Use didn't turn out that way, but all in all, I think most cases are difficult to fudge. On the other hand, Public Benefit is a scenario that is easy to abuse. Kelo was based on future projections of developments and revenue. And it turns out the future is often quite fickle. In the case of Kelo, the development did not occur and not tax benefits occurred. So no actual Public Benefit occurred.

Question: In all of these rulings, has the bench ever set down any standard for what constitutes a Public Benefit? Anyone with a spreadsheet can show future financial gains that will never actually occur.

I still stand by my belief that Midkiff v. Hawaii Housing Authority is still a thousand times worse. Kelo at least involved a mixed-use area with some of the property going to public use, others to private use. Midkiff literally involved taking property belonging to land owners and giving it to different, smaller landowners. Now breaking up land oligopies were probably a good idea given the questionable methods in which the land was first acquired at times, but it was blatantly taking private property for private use.

Well then if he didn't know the law it's a good thing he retired.

[…] Click here for the article. […]

[…] most unpopular opinion I ever wrote, no doubt about it.” Legal scholar Ilya Somin, among others, has argued that it’s also poorly reasoned. And despite some states’ attempts to limit the “public […]