Mitch Daniels on How to Cut Government & Improve Services

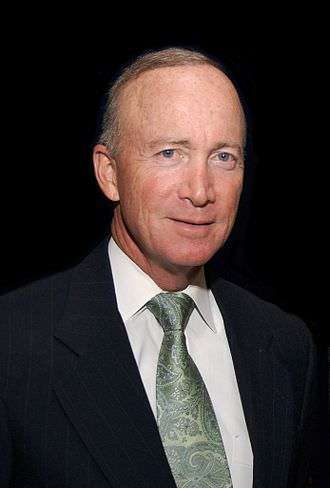

The former Indiana governor and current president of Purdue University gets real about making the public sector cheaper - and better.

HD DownloadWhen Mitch Daniels served as a hugely popular governor of Indiana between 2005 and 2013, he would apply what he called the "Yellow Pages Test." Which is to say: If a good or service had multiple providers listed in the business section of the telephone directory, the government shouldn't be doing it.

Prior to being elected governor, Daniels had served as President George W. Bush's first director of the Office of Management and Budget. A lawyer by training, Daniels has also worked at pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and headed up the Hudson Institute, a think tank founded by futurist Herman Kahn.

During his eight years in office, Daniels led one of most successful cost-cutting and privatization campaigns in modern political history. He contracted out welfare services, started a school-voucher program, slashed the size of the state work force, and ended collective bargaining for public employees. In one of his most controversial moves, Daniels leased a money-losing 157-mile toll road to a group of private investors in a deal that brought nearly $4 billion to the state*.

By the end of his second term, Indiana's public-sector employment was 18 percent smaller, its credit rating was upgraded to AAA for the first time in history, and even the state's long-hated Bureau of Motor Vehicles had become known for its excellent customer service. His outstanding record as governor led some Republicans to pine openly for Daniels to run for the 2012 GOP presidential nomination but he declined.

Daniels credits the work of Reason Foundation, especially of co-founder Robert W. Poole, Jr. with helping him identify and work through innovative ways to improve public services while controlling costs. He also cites former Reason Editor Virginia Postrel's 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies as one of the most powerful influences on his strategic thinking and planning.

Now the president of Purdue University, the 66-year-old Daniels has kept his thrifty habits intact, privatizing some services and applying a tuition freeze to keep higher education affordable for middle class families.

This May, Mitch Daniels became the first recipient of the Reason Foundation's annual Savas Award for Public-Private Partnerships, which is awarded to policymakers with outstanding legacies of improving the delivery and effectiveness of services while reducing the cost and scope of government.

Reason magazine Editor in Chief Matt Welch interviewed Daniels in New York City shortly before the award was presented. Among the topics covered: How Daniels cut the public-sector work force in Indiana and ended collective bargaining without much controversy; the surprising, bipartisan pushback on leasing the Indiana Toll Road; his challenges and plans for Purdue, including an ongoing tuition freeze; runaway spending by Republicans during the Bush years; the need for old-age entitlement reform and reduction in national debt; and more.

About 30 minutes. Scroll below for a rush transcript of the interview and downloadable versions. Subscribe to Reason TV's YouTube channel to receive automatic emails when new material goes live.

Produced by Joshua Swain; camera work and introducution by Jim Epstein; additional camera by Anthony L. Fisher.

NOTE: This is a rush transcript. All quotes should be checked against the audio for accuracy.

REASON: You inherited deficits of $200 million. Why public sector unions? Why was that a focus straight off the bat? What's the importance of that?

Mitch Daniels: Well, it wasn't primarily about money. We had to address that the old fashioned way and reconcile spending with revenue and so forth. No, it was much more about call them work rules, but there were something like 160 pages of do's and don't's in these agreements that the state had signed and I used to say you couldn't pick up a coffee cup from one desk and move it to the next without a 30-day, 60-day consultation with somebody. And you certainly couldn't, as we were determined to do, to combine departments, break off departments for more direct supervision. You certainly couldn't outsource anything under those conditions. We'd been paralyzed really from doing those things that would make government work, so it was much more about making a totally dysfunctional government operate effectively within the zone, the more limited zone that we thought it ought to operate at all.

REASON: Wisconsin became the site of three years' worth of scuttlebutt over this, even though there was Hurricane Mitch and I'm sure it felt crazy in the eye of the storm. It didn't feel like the same kind of thing. Why didn't that happen in Indiana?

Mitch Daniels: Well, we were able to strike quickly and did. Here's a confession: I don't often procrastinate or over-cogitate and so forth, but on that decision, I really spent a long time. I was trying to talk myself into either waiting until after the legislative session or maybe splitting the baby somehow, maybe these important departments and not these. The key distinction was we didn't need legislation as in almost every other venue including the federal government when JFK did it, collective bargaining which FDR and Fiorello LaGuardia and lots of friends of unions always said had no place in the public sector, had gotten there almost always through executive orders later codified in statute. Indiana, the advocates of collective bargaining never got into statute so I had the ability which Walker did not, to take it out by executive order. I tried to persuade myself, though, that maybe we shouldn't do it right away because I could imagine a scene like we saw in Wisconsin and I thought, man, the whole rest of the agenda—we've got this huge agenda of things that we think are really important to do, and I could imagine all being brought to a halt if we had an eruption like they did.

Instead, I just finally decided, no, we cannot fix this place under these conditions. We're just going to have to take this action and hope for the best, so I went and told the union leaders myself my first day in office. I thought they deserved to hear it from me. Went back, signed the order, pulled up the covers and held my breath and nothing happened, except that over the first about 11 months, 90+% of the state employees stopped paying their dues. Once it was their choice, they gave themselves a pay raise. I think the swiftness maybe. Maybe they just didn't think we'd do it, but we did it and then their members began to speak, at least tacitly, and it was never an issue.

REASON: This led to be able to reduce the state workforce by some 18%. Tell us about the knock-on practical benefits that you've received from doing that?

Mitch Daniels: Some of it's had to do simply with being able to organize the government for better effect. A good example: we had the worst child protection system in the country. HHS was fining us and probably deservedly so. The ratios of people who were supposed to be watching over these endangered children were way out of whack. No training and all that, so we had pledged to do something direct about that. Pulled it out of this massive social services bureaucracy and created a unit entirely of its own reporting directly to the governor and five years later, we were winning national awards, but that sort of restructuring or combining units and extracting the synergies that were possible there.

In most of life, I've always said I'm pretty much a libertarian, but when it comes to IT I believe in dictatorship. You can't let everybody have their own computers and their own little customized software so that nothing talks to each other, right? And so establishing one unitary and unified IT system across all of government. I still bump into people who said how did you get that done because it's a problem that afflicts lot of large organizations, private and public, and so things like that. We were able to go straight for them.

We went right away to a new benefits plan which is HSAs. Indiana rather quickly had almost all state employees on what we now call a consumerist or a high deductible plan. The penetration of such plans in public sector America last I looked was about 1 or 2% and we must've been half of that because we were 90+. Couldn't have done that. Saved buckets of money. Employees wound up with millions of dollars accumulating in their accounts which were theirs. You know how that works. And likewise, Indiana as far as I know is still the only state that has.

We reformed the civil service rules such that employees are paid for performance, not in lockstep grids. The best performers got the biggest pay raises by far in state history. Those at the other end got a warning and often second chance, but that's all they got.

So, those were the sorts of things. Now, that translated into dollars. Sure, it did. But I did some stressing here that our principal objective was to demonstrate that government actually could deliver. Every state hates its license branches, right? I guarantee you, Indiana probably had a candidate for the worst. I used to say that people went to an Indiana Bureau of Motor Vehicles office with a box lunch and a copy of War & Peace and hoped not to finish both of them before somebody noticed they were there. So, by about three or four years in, they're winning national awards. I'd get a report once a month, the average visit time door to door was down to nine minutes and something. The average customer satisfaction was 97%.

REASON: At a DMV?

Mitch Daniels: That's right.

REASON: That's crazy talk. I live in Brooklyn, and I think the average time is 5½ days or something.

Mitch Daniels: Business school cases have been written about it. It's a very interesting story all by itself. A lot of that was accomplished, by the way, by creating all sorts of ways that you didn't have to go to the branch in the first place if you didn't want. Online, in the mail, on the phone, etc.

I was really fixed on those things that touched lots of people, so everybody has to deal with the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. Everybody has to deal with the Department of Revenue. We really worked hard on those.

REASON: So people could see the practical benefits and understand.

Mitch Daniels: Yes. And I saw that also as an important investment of capital in that metaphorical sense, because, first of all, I'm a limited government person of the first order, but I don't think that unadulterated cynicism about government is healthy for our democracy and so, no. 1, I wanted people to develop a sense of confidence that the folks running the people's business really were committed to try to do it well.

And the second thing was, I wanted to build momentum for the next reform and literally I think a lot of people concluded, well, they can fix the damn DMV, maybe that new idea they've got is worth a look, too.

REASON: Talk a little bit about privatization, both in terms of what you did there, but also where did you get acquainted with and enamored with the idea to begin with?

Mitch Daniels: In the early '90s, a lot of people were enamored with it. I was convinced it was such an obvious and smart thing to do so a fellow named Osborne was reputed to be Bill Clinton's favorite thinker at the time and he writes a book Reinventing Government or something was the title. And it's all about this, using the private sector where appropriate to deliver services more effectively and efficiently.

A friend and a really good public official named Steve Goldsmith got elected mayor in my hometown and when he was running, I said to him you're going to want a signature thing. Your predecessors have had some big ones and you should want one. I said this business of privatizing services for the benefit of service recipients and taxpayers is a good one. I said, why don't you have a citizens' commission to go look through state government and see where the opportunities are and aren't. Big mistake because he makes me the chairman of the commission. We got some great people, some good businesspeople and they divided local government into functional areas and people went in and came out with a host of ideas, so that's where I got— And most of them got acted on, so that's where I guess got the notion but I got a lot of it from reading Reason Magazine, not to kiss up here, but it's true, all this at a time when I had no intention, no premonition that I'd ever hold elected office myself. I just never expected that to be the case, but when it came along, I had the benefit of the reading I'd done and that one experience.

REASON: The most notorious or infamous or something, at least controversial, privatization was I guess one of your first which is the toll road. Why was that controversial? Of all things in the world to be controversial.

Mitch Daniels: It's an interesting thing, because it is beyond any question was a slam dunk grand slam spectacular success. We were very self-critical in our administration. Most things, you know, give yourself a B or a B+, but not this one. We had valued the road in public hands around $1.3 billion, $1.4 billion, and you had to make some rosy assumptions to get it up to that and I had told myself if the bids come in— If the bids aren't well over $2, we probably won't— It won't be worth going for it, but if they get up there closer to what we're aiming at, we well, so the bid comes in $3.9 billion. Unbelievable. And when I announced on a Monday morning into a jam-packed room, there were gasps and cheers and clapping and everybody in that room at that moment believed this thing would fly because holy cow, well, you saw what happened? Xenophobia happened. The notion that—

Well, first of all, there was just some vague sense which our partisan opposition pounced on, that maybe we were giving something up. People didn't understand necessarily the transaction at the beginning and then the fact that the financing was organized by a foreign entity, Australian bank—

REASON: You know how those Australians can be, come on.

Mitch Daniels: Yeah. A friend of mine said he went in a barber shop when the thing was really white hot and people were in there arguing about it and he finally said you're right, it's even worse than I thought. I'd just been out there. They've changed all the signs to Australian. So it became what could have been and should have been— A bipartisan celebration became a very partisan thing, but we got it through and the results speak for themselves. We're in the tenth of 10 consecutive years of record infrastructure investment in Indiana and there were more than 200 projects that wouldn't have happened that did, including some big ones that people had waited for literally for decades and a big fraction of all the bridges in the state were rebuilt, so there's still more to do. Always will be, but it was a tremendous piece of luck for the state.

Here's the thing that haunts me. On that day when I made that announcement, I pointed out that as of the closing that we were headed for, this would be the largest such transaction in American history by a factor of 2. It was about twice as big as the Chicago Skyway which was the biggest one at the time. I said, but what won't last. That won't last a year because this is such an obvious partial answer to the national problem we have of infrastructure that other places— It's being done all over the world already anyway. It's just a little late getting here to America. Look for this to happen in a lot of other places. Astonishingly to me, we sit here a decade later and it's still the record and that's a darn shame.

REASON: Your record has governor of Indiana at time when we went through the financial crisis when we started seeing trillion dollar annual federal deficits got you very much in the conversation in the 2012 presidential race like he's the coming wonk that we need and somewhere in 2010, I guess you made a statement that had libertarians just high-fiving and conservatives not quite so high-fiving about how Republicans are conservatives and need to start thinking in terms of a truce on social issues. Looking back on that and transposing it to today, do you still feel that and what's your assessment of the way the Republicans are going after issues like gay marriage or pot legalization or even immigration if you see that as a social issue?

Mitch Daniels: It's still my view. By the way, the comment wasn't directed just at so-called conservatives. It was directed at their opponents on the other side, too. It was a general appeal based on my belief which is stronger now several trillion dollars of debt later than it was then that we have urgent problems. We've got to get this country on a pro-growth footing. We need years of consistent high growth if we're going to remain a country of upward mobility and opportunity and we've got to begin the process of flattening this debt burden we're about to dump on future generations and I thought that it would be wise to try to rally the nation and focus the nation on these problems which we all share and I chose the word truce advisedly to distinguish it from surrender or retreat. Just stand down, agree to disagree. Let's try to see if we can't work on those things that genuinely threaten us all. That was the idea and I think it's absolutely true today.

We've just come through a little storm in my home state where I think there were some misunderstandings and some unfairness and all that, but still, I think it illustrates the fact that these kind of issues can get in the way of truly serious business.

I think that this idea has a lot more agreement than many people think it does. Even in 2012— 2011, actually. After I had retained my senses, not run for national office, a Wall Street Journal reporter who had trailed me around a little bit and I'd gotten to know, called and said they had put a question on that subject on their poll and Republican primary voters agreed with the idea of the truce by something like 7 to 1, so there're people who're very passionate about those issues. They have a right to be and they will be heard but I think in growing numbers, Americans are more concerned about other things and many more are inclined to a live and let live attitude.

REASON: How terrified are you of an $18 trillion debt and the entitlements coming and washing down when there doesn't seem to be a lot of discussion even on the Republican side anymore about doing much about that? What is your articulated dread when you wake up in the night sweating and thinking about the future of our accounts?

Mitch Daniels: It's going to be a huge drag on growth. It already is. Just wait until interest rates return to anything like normal from these artificial levels and there are certainly situations in which it could threaten the country's future more seriously than that and there's a moral aspect to it. By the way, I don't blame the American people. They've been misled about how all these things work—it's just my money, you know, they stuck it in a drawer for me. I'm just taking it out. People have been actively misled about it and I don't think too many of our fellow Americans knowingly would plunder their children, would borrow tons of money and spend it on themselves, on consumption for themselves today. That's exactly what we're doing, so I think there's a moral dimension, an economic dimension. I even worry about national security implications of a country that will soon be spending upwards of two-thirds of all its money on transfer payments and interests.

REASON: You were director of the Office of Management and Budget at the kind of the dawn of the Bush era. Bush, looking in hindsight, was no great fiscal steward of these United States even if you isolate military post-9/11 spending. What went wrong with Bush conservativism and fiscal conservativism?

Mitch Daniels: Those numbers I think have been largely misrepresented. I'm not defending every decision that was made at that time. I would've strongly preferred less spending than happened, but the first thing that went wrong was a bubble burst, so everybody— I was one of the guilty parties, although so was Alan Greenspan, so was the Congressional Budget Office, so was everybody, the Federal Reserve and everybody else around, misunderstood that the revenue that was coming in temporarily in the late '90s was a base from which you could project some sort of growth. It wasn't. And when the stock market bubble burst, those revenues, a lot of them evaporated, so the apparent fiscal strength of the country was somewhat illusory. Then there was a recession that followed the bubble. Then comes the war, the decision right or wrong to build a homeland security capability and all these things piled up on top, so I think after you've factored all those things, yeah, there was some spending, sometimes to accommodate a Congress that was reluctant necessarily to fund the war on terror spending.

REASON: It's a unified Republican Congress for a large part of that.

Mitch Daniels: A big part of that time, and so, again, I think it's really ahistorical to suggest that somehow he just spent a flush Treasury bare. That's just not what happened.

REASON: I think it's more than total federal spending non-defense grew by 50% in eight years, which is not fiscally conservative by any stretch of the imagination.

Mitch Daniels: Yeah. As I sometimes said, I never had a disagreement with anybody during the 2½ years I was there where I was for more spending than they were. When we got a chance in Indiana to deal with a fewer zeroes but a very serious fiscal problem, we found a way to do so.

REASON: You were referencing Reinventing Government in the 1990s and intellectual stuff and even our recent former editor, a beloved figure, Virginia Postrel wrote a book called The Future and Its Enemies and I understand that that had some influence on you. Talk about that.

Mitch Daniels: I thought it was a wonderful insight. And it certainly informed or colored my thinking when I got to office. The dichotomy she illustrated between stasis and dynamism and those who are comfortable with change recognize that it's largely inevitable and therefore the goal ought to be to shape it and adapt to it effectively. And as I mentioned already, Indiana historically has been a change adverse state and our whole argument, everything we said and everything we tried to, a speech that I gave for 10 years basically, had as their central theme that won't work anymore, that if you tread water in this world, you will sink and if you stand still, you will be passed by and I wanted Indiana to be an active vanguard state and I think I can document that after eight years, we were. We were looked to in a variety of ways, whether it's infrastructure or fiscal probity or education reform or property tax controls or you name it or government that works.

REASON: Talk about your role. Purdue a little bit here in most of the country, including where I'm from—California—the story about universities is all about a higher education bubble. It's about tuitions trending like this. You've actually cut tuitions. Do I have this right?

Mitch Daniels: Frozen.

REASON: How have you been able to do that?

Mitch Daniels: Edict. I mean, I don't consider that we've done anything particularly dramatic yet. I suggested to our board that we do this and I'd only been there two or three months when the decision had to be made so I didn't have nearly the information to be sure but I had a suspicion that we could do it, and limits have a lot of value. That's why balanced budget requirements lead people to make decisions they wouldn't otherwise make, establish priorities that they wouldn't otherwise establish. In business, when times are flush, people are not as attentive to that expense account or the less essential items. Sales go flat, suddenly people sharpen their pencils, so I thought if we established that limit and I said to the campus, we all care about this, don't we? We all would like this to remain a school that students from any income level if they can meet our standards can afford to attend and people at Purdue do agree with that—faculty, staff, everybody, so I said let's all find ways to do this. I said let's try something different. Instead of asking our students' families to adjust their budgets to our preferred spending, let's adjust our spending to their budgets.

We did it once and then we were able as it turned out to extend it. This second year it'll be at least one more year. To an extent, it's a statement that we believe that higher education ought to be of the highest possible value and that controlling costs, maintaining access to the extent we can is an important part of that.

REASON: How have you done it? What's the blueprint for Purdue?

Mitch Daniels: Well, people always want to know some great master stroke. There weren't too many of those. We had a very very expensive health care benefit plan. We modernized it. It's more consumerist and it's over-performing in terms of, as it has all over the country. The minute people get a little bit of skin back in the game, they start to ask common sense questions. They experienced that in Indiana state government in a big way, so that was one. We consolidated information technology there, too, a big big savings.

REASON: I think you being involved with two successful large-scale IT projects put you on a very short list of people.

Mitch Daniels: Well, I won't claim to have contributed anything except the determination that it had to happen.

REASON: For those of us who don't spend a lot of time on college campuses and get our information through oftentimes partisan media, it can seem like it's just a hell broth of micro-triggering and people in free speech cages over in a corner. What's your assessment of the climate of free speech on campus nationwide and at Purdue? Is it as bad as some of us suspect?

Mitch Daniels: In places it obviously is. We all read about them and you just shake your head. I can tell you that Purdue's different and I think you don't hear about the places where free speech is respected and protected. Naturally enough you don't. We feel very strongly about it. About to take some future actions to insure that what's been a good record remains that way and we've indentified some small policies that were less than ideal and we're changing those but, no, I think that the spirit of free inquiry is still strong on our campus and I hope on most, but clearly there are places where it's violated in truly unfortunate ways.

REASON: Thank you very much.

Mitch Daniels: I enjoyed it. Thanks for the good work and the provocative work that Reason's always done. Always been a courageous place and one that held faithful to principle that's why I've been a reader and often agreed. Not always, but was always stimulated.

REASON: You mean you're not ready to legalize heroin? I don't understand. …

Mitch Daniels: Stop short of that, yeah.

* Original text had an error here since deleted.

Show Comments (0)