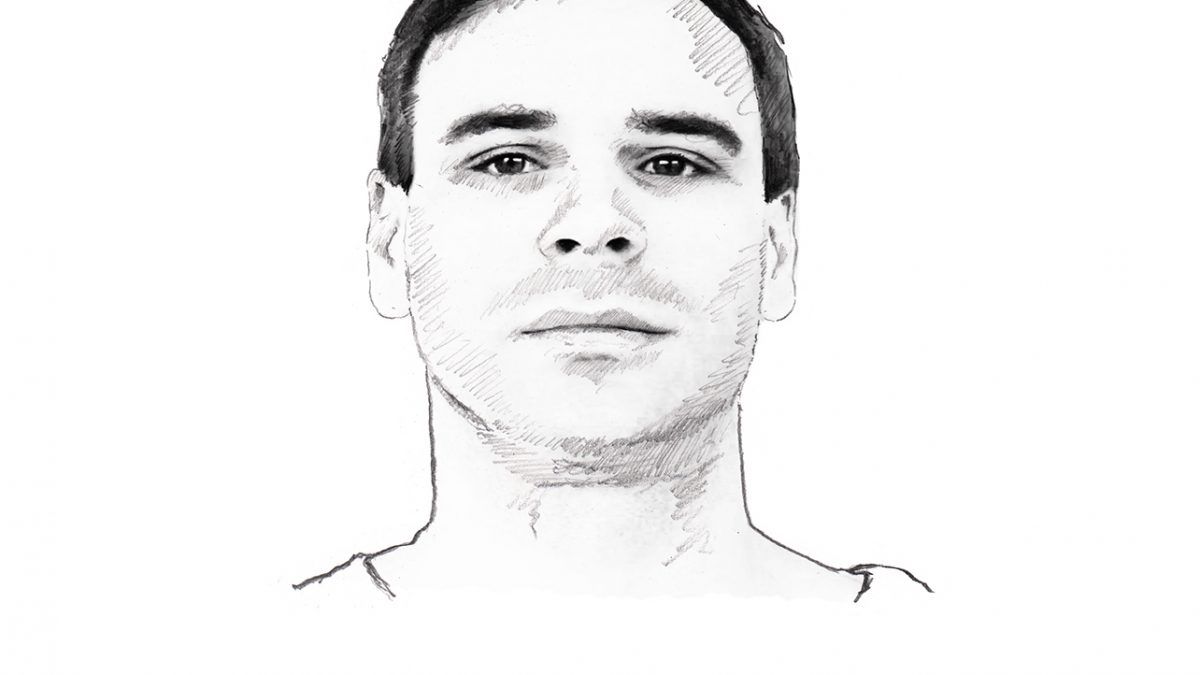

This Man Is on Death Row for Killing a 6-Month-Old. But What If We're Wrong About Shaken Baby Syndrome?

A controversial medical examiner, exaggerated testimony, and bad forensics branded Jeffrey Havard a rapist and a baby killer.

Jeffrey Havard's story began the evening of February 21, 2002, when the Mississippi man was keeping an eye on Chloe, the 6-month-old daughter of his girlfriend, Rebecca Britt. According to Havard, Chloe had spit up on her clothes and bedding, so he gave the girl a bath. As he pulled her up out of the tub, she slipped from his grip and fell. As she fell, her head struck the toilet.

Havard would later say the bump on Chloe's head didn't appear serious, so he dressed her in clean clothes and put her to bed. Not wanting to worry Britt (or perhaps not wanting to anger her), he said nothing about the incident when she returned. When she did get home, Britt checked on the baby, who seemed fine. So she and Havard ate dinner and went about their evening.

Later that night, Chloe stopped breathing. Havard and Britt rushed her to a hospital. She died shortly thereafter.

When the emergency room doctors examined Chloe, they discovered that her anus was dilated—which isn't uncommon in infants shortly after death. It's also common in infants who are still alive but have lost brain function. Unfortunately, though, even trained medical staff sometimes mistake it for sexual abuse.

Medical examiner Steven Hayne performed an autopsy the following evening. In his write-up, he noted a one-centimeter contusion on Chloe's rectum, which he documented in a photograph. The report did not mention any evidence of sexual assault, but Hayne did find symptoms he said were consistent with "shaken baby syndrome."

Havard didn't admit that he'd dropped Chloe until a video-taped interview two days after her death, which meant his story had changed. That, plus statements E.R. staff made about possible sexual abuse and Hayne's shaken baby diagnosis, were enough for local officials to arrest Havard and charge him with capital murder. The district attorney said he would seek the death penalty.

* * *

The concept of shaken baby syndrome has, in fact, come under scrutiny over the last decade. It's obviously true that shaking too hard can kill a fragile newborn—that's not disputed. But prosecutors have become reliant on the idea that if a trio of specific symptoms are found in a dead child, the death could only have been caused by violent shaking. Those symptoms are bleeding at the back of the eye, bleeding in the protective area of the brain, and brain swelling.

This is a convenient diagnosis, since it provides prosecutors with a method of homicide (shaking), a likely suspect (the last person alone with the child), and intent (it is assumed that babies only die this way after exceptionally violent shaking). Yet new research has shown that falls, blows to the head, and even some illnesses and genetic conditions can cause the same set of symptoms. Many medical and legal authorities have therefore concluded that the trio of symptoms shouldn't be the sole basis of a conviction. Even the doctor who first came up with the theory has now expressed doubts about it.

In most shaken baby syndrome cases, prosecutors would first file murder charges, then later allow the defendant to plead down to a lesser charge like manslaughter. But sometimes they've gotten a murder conviction.

In recent years, thanks to increasing doubt around the diagnosis, a number of these shaken baby convictions have been overturned, and many more are under review. A 2015 study by The Washington Post and Northwestern University's Medill Justice Project found more than 2,000 cases in which a defendant was charged with shaking a child. Of those, 200 have either been acquitted, had the charges dropped, or had their convictions overturned. The National Registry of Exonerations lists 14 people convicted because of a shaken baby diagnosis who were later cleared.

Without DNA testing, however, it can be nearly impossible to overcome faulty forensic testimony—even when, on close examination, it turns out the courts went out of their way not to see problems with the arguments they were accepting.

* * *

After Jeffrey Havard was arrested, the court assigned him a public defender. His attorney asked the district court judge for funds to hire his own forensic pathologist, but the judge turned him down, finding that there was no need for a separate pathologist when Hayne was available.

Hayne has since come under intense scrutiny for taking on improbable workloads and for giving testimony that at times has stretched the bounds of science. In fact, courts have thrown out his testimony in several cases, and he has been barred from doing autopsies for the state of Mississippi. In another shaken baby syndrome trial six years after Havard's conviction—well after the problems with the diagnosis were known—Hayne cited a study that does not appear to exist, and referred to a forensic pathology textbook that says the precise opposite of what he claimed in court. "I don't know how he could have honestly misread it," the textbook's author would later declare.

Even at the time of Havard's trial, there was good reason for the defense attorney to want a second opinion. In other cases, Hayne had admitted under oath to doing 1,500 or more autopsies each year—nearly five times the absolute maximum recommended by the National Association of Medical Examiners. But the state's courts and prosecutors had been relying on Hayne for 15 years. Havard would have to rely on him, too.

Though he had no prior history of abusing or molesting children, by the time Havard's trial began 10 months later, word had spread around Adams County, Mississippi, that he was a pedophile and baby killer.

Studies have shown not only that an eyewitness's memory can change over time, but that memories can be significantly altered with the acquisition of new information. Research supporting the idea of "reconstructive memory" in fact goes all the way back to the 1930s and the work of cognitive psychology pioneer Frederic Bartlett.

This appears to be what happened in Havard's case, as some witnesses' memories grew considerably more vivid by the time of his trial. Jurors heard the sheriff, the coroner, and the hospital staff describe "tears," "rips," "lacerations," and other injuries to the child's anus. Some claimed to have seen blood. Two nurses said it was the worst example of anal trauma they had ever witnessed. Yet once the infant had been cleaned off, Hayne's autopsy photos showed no rips, tears, lacerations, or similar injuries anywhere on the girl's rectum—only the dilation and small contusion.

Even the doctor who first came up with shaken baby syndrome has now expressed doubts about it.

Despite his own photos, and despite the fact that his autopsy notes made no mention of sexual abuse, Hayne played up the bruise at trial. He told the jury that it was an inch long rather than a centimeter, as his report had said. While he conceded that he had found no tears or lacerations, he speculated that rigor mortis (the tightening of muscles after death) could have caused the girl's rectum to close and that this could have hidden any tears or cuts from his view. If he had really believed that, Hayne could have accounted for the possibility in his autopsy and looked more closely. He did neither. When asked what might have caused the small bruise, Hayne volunteered, "penetration of the rectum by an object."

The examiner also testified that he'd found the symptoms of shaken baby syndrome and could conclude that Chloe had been "violently shaken" to death. To emphasize the point, Hayne and the prosecutor exchanged the phrase "violently shaken" an additional six times.

The defense attorney wasn't exactly aggressive. The prosecution called 16 witnesses, whose testimonies comprise 261 pages of the trial transcript. Havard's lawyer called a single witness, a nurse at the E.R., whose testimony takes up three pages. The state didn't even bother to cross-examine him.

It's hardly surprising, then, that the jury convicted Havard and sentenced him to die. The entire trial, deliberation, guilty verdict, sentencing trial, deliberation, and death sentence took two days.

* * *

Havard's case was taken up by the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel, an institution the state had set up to guarantee that indigent defendants in death penalty cases receive adequate legal representation. That office had funding to hire its own experts, so Havard's new attorneys asked former Alabama state medical examiner James Lauridson to review Hayne's autopsy and trial testimony.

Lauridson found a number of problems. Most notably, he found no evidence of sexual abuse at all.

His report pointed to medical literature documenting the fact that the anus often dilates in infants shortly after death, and that this is often mistaken for sexual abuse. It disputed Hayne's contention about rigor mortis and speculated that the E.R. staff likely mistook the exposed lining of the girl's rectum for blood. Lauridson initially had difficulty getting his hands on the slides containing the tissue samples Hayne had taken; when he did receive them, after his initial report had already been submitted, he found nothing to suggest sexual abuse.

None of these opinions mattered for Havard's direct appeal. In a 2006 ruling, the Mississippi Supreme Court delivered a brutal one-two punch. The justices first upheld the trial judge's decision to deny Havard funds to hire his own forensic pathologist, finding that the defense attorneys had failed to show why an independent medical examiner was necessary. They then explained that because Lauridson's affidavit wasn't submitted during the original trial, they were barred from considering it. Thus, the court unanimously upheld Havard's conviction and death sentence.

Havard's first post-conviction appeal came two years later. In these proceedings, a defendant has more leeway to introduce new evidence, but the bar to be granted a new trial is also set much higher.

This time, the court had to at least consider Lauridson's affidavit. And it did—but not all that carefully. In his majority opinion, Justice George Carlson wrote that Lauridson "opined in his affidavit 'that there is a possibility that Chloe Madison Britt was not sexually assaulted.'" Carlson then wrote, "Taking this statement to its logical conclusion, this leaves open the possibility that she was."

In reality, the phrase "there is a possibility," which Carlson put in quotes, doesn't appear anywhere in Lauridson's affidavit. What the examiner actually wrote was: "The conclusions that Chloe Britt suffered sexual abuse are not supported by objective evidence and are wrong." He did add that he couldn't definitively say there were no signs of sexual abuse, because that would require examination of Hayne's tissue slides—and at the time of his original report, he still didn't have access to them. When he finally saw the slides, however, he was much more conclusive, writing that there was "no histological evidence of contusion or laceration" on the child's colon or anus and that "these findings further strengthen the conclusions of my report."

Nonetheless, Justice Carlson mischaracterized Lauridson's report throughout his opinion. It was arguably a more forceful brief for the state than those submitted by the prosecutors themselves. By an 8–1 vote, Havard's appeal was denied and his conviction and sentence were upheld.

* * *

In late 2011, Havard's attorneys asked for a new trial. In the intervening years, Hayne had carefully changed his opinion: "Based upon the autopsy evidence available regarding the death of Chloe Britt," the medical examiner wrote in a declaration for Havard's lawyers, "I cannot include or exclude to a reasonable degree of medical certainty that she was sexually assaulted." He also acknowledged that a dilated anus is not in itself evidence of sexual abuse.

Even here, Hayne was hard to pin down, managing to reframe his trial testimony without directly contradicting it. He now claimed that he had never explicitly said Chloe was sexually assaulted—he'd merely said her injuries were consistent with that possibility, then speculated that one method of assault could have been "penetration of the rectum by an object." That wasn't entirely wrong, though the "penetration" line had to have been pretty damning for Havard. The prosecutor did do most of the heavy lifting to advance the assault narrative, often by citing the observations of the E.R. staff, sheriff, and coroner. For most of his testimony, Hayne merely acquiesced, even though he knew he'd found no biological material from Havard on or in the child, and even though the only anal trauma he'd seen was the small bruise.

A credible and conscientious medical examiner should have said at trial what Hayne said in his declaration a decade later. A credible and conscientious medical examiner wouldn't have allowed his own testimony to be used by a prosecutor to mislead a jury, even if that testimony wasn't technically false. But Hayne wasn't a credible and conscientious medical examiner.

The Mississippi Supreme Court again denied Havard relief. Justice Carlson again wrote the opinion.

Since Hayne hadn't explicitly testified at trial that Chloe had been sexually abused, Carlson argued, his 2012 declaration stating he had found no evidence of abuse wasn't really new evidence. Of course, in his 2008 opinion, Carlson had described Lauridson's conclusion that the dilated anus was not indicative of sexual abuse as "contrary to that of Dr. Hayne." Hayne may not have said the dilation was caused by sexual assault, in other words—but his testimony was so suggestive of it that even Carlson at the time seemed to think it was Hayne's position.

It took Havard's original jury less than two days to deliberate, convict him based on flawed evidence, hear arguments regarding the appropriate punishment, deliberate again, and sentence him to death. It took 13 years for the courts to admit that a small portion of the evidence might have been scientifically unsound.

In two rulings handed down just four years apart, the same state Supreme Court justice had found that Hayne's testimony supported the jury's finding of sexual assault and that Hayne never explicitly testified that a sexual assault had taken place.

Absurdly, Carlson additionally claimed that the examiner's 2012 declaration wasn't new evidence because it was "duplicative" of the Lauridson affidavit that the court had dismissed in 2008. Between the two opinions, then, he managed to assert that Lauridson's affidavit contradicted Hayne's trial testimony; that there was no substantial difference between Hayne's trial testimony and his updated declaration; and yet that Hayne's updated declaration duplicated Lauridson's affidavit.

Logically, these three things can't possibly all be true. Two affidavits can't be both duplicative of and contrary to one another. But Carlson stated exactly that, and so did his fellow justices. For the third time, Mississippi's Supreme Court denied Havard's petition.

* * *

Over the next several years, the state's case against Havard continued to deteriorate. Two more forensic pathologists reviewed the case and wrote scathing reports deriding Hayne's work, as did an engineer who had studied the mechanics of shaken baby syndrome. By 2013, Havard's situation had also attracted popular attention. The Jackson Clarion-Ledger and the Huffington Post had both published articles about him, and a website and Facebook page maintained by Havard's friends and family were generating outrage over his conviction.

Meanwhile, Hayne was garnering less-welcome attention. His testimony in several other cases had been criticized by fellow forensic pathologists. In 2008, he was effectively fired as the de facto medical examiner of Mississippi—partially in response to a 2006 investigation in Reason by Balko, a co-author of this piece. State officials including Attorney General Jim Hood were soon facing calls to review Hayne's work, although they steadfastly resisted.

Havard's attorneys were also pursuing his claims in federal court during this period. In August 2013, Hood's office filed a motion to seal that case—to prohibit the public from seeing any further filings or proceedings. The state claimed the motion was sparked by a Facebook post from one of Havard's lawyers, who had complained that Mississippi didn't "want to be bothered by actually responding to his claims of innocence." But the state's brief itself revealed the real motivation: Havard's case "had become a public spectacle."

Hood said his office had received letters from Havard's supporters and expressed concern that the letters were similarly worded, which he claimed showed the authors had all gotten their information from the same source. Why this was a grave matter isn't exactly clear. There's nothing inherently wrong with citizens petitioning their elected officials. In the end, not only did the federal court reject the attorney general's motion but the motion itself became a news story, fueling speculation that the state had something to hide.

In 2014, Hayne appeared to walk back his trial testimony even further. In an interview with the Clarion-Ledger, he said he'd never believed Chloe Britt had been sexually assaulted. The following July, he filed another affidavit with Havard's trial attorneys, this time claiming he had explicitly told prosecutors on more than one occasion that he could not support such a finding. Havard's attorneys said this information was never turned over to them.

Someone wasn't telling the truth. At Havard's trial, the prosecutor had informed jurors that Hayne would "testify for you about his findings and about how he confirmed the nurses' and doctors' worst fears—this child had been abused and the child had been penetrated." Now, all this time later, Hayne was claiming he'd told prosecutors precisely the opposite.

If true, that would be a major violation on the part of the state. Hayne's statement would have been exculpatory information, and prosecutors would have been obligated to share it with the defense. Hayne was the only medical examiner to testify, and the alleged sexual assault was a major part of the state's case and the aggravating factor that allowed Mississippi to seek the death penalty.

It's hard not to wonder: If Hayne really knew all along that the state had persuaded a jury to convict someone of an assault he never believed happened, why did he wait 13 years—and until three other forensic pathologists had filed affidavits for Havard's defense—before speaking up?

* * *

In April 2015, Havard finally caught a break. Justice Carlson had retired, and the Mississippi Supreme Court gave Havard's lawyers permission to request an evidentiary hearing on the scientific validity of shaken baby syndrome.

The court still rejected Havard's challenge to the allegations of sexual abuse. The ruling wasn't an exoneration, and it wasn't a new trial. It was a three-paragraph order allowing Havard to ask a trial court judge to hold a hearing about the soundness of the evidence that had been used against him. It was a modest win, but it at least put his execution on hold.

In June 2016, a circuit court judge granted his request. If Havard could convince the court that shaken baby syndrome is not a scientifically reliable diagnosis, he would finally get a new trial.

That hearing occurred in August 2017. Hayne testified that he no longer believed in the shaken baby diagnosis. The renowned forensic pathologist Michael Baden also testified for Havard's defense, saying he didn't believe Chloe Britt had been shaken. In keeping with the state supreme court's ruling, the judge refused to allow any testimony casting doubt on the alleged sexual assault.

It took Havard's original jury less than two days to deliberate, convict him based on flawed evidence, hear arguments regarding the appropriate punishment, deliberate again, and sentence him to death. It took 13 years for the courts to admit that a small portion of the evidence might have been scientifically unsound. It took another 14 months for the trial court judge to agree to hold a hearing on the matter, and 14 months more until the hearing itself. As of press time, the judge had yet to issue a decision.

It's often said that the wheels of justice grind slowly. That isn't always true. When it comes to convicting people, they can move swiftly indeed. It's when the system needs to correct an injustice—to admit and address its mistakes—that the gears tend to sputter to a halt.

For now, Jeffrey Havard remains on death row.

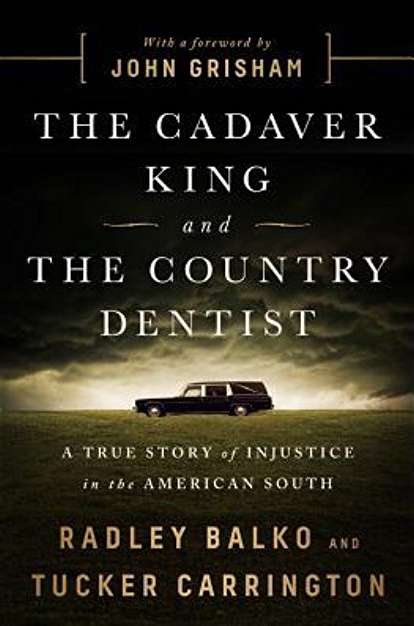

This article has been adapted from their new book, The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist: A True Story of Injustice in the American South, by permission from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group Inc. Copyright © 2018

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Junk Science Branded Him a Rapist and a Baby Killer."

Show Comments (72)