If You See the Trump Biopic Before Election Day, Thank Citizens United

At its core, the oft-denigrated decision revolved around whether the government can censor information leading up to an election.

A biopic about former President Donald Trump opens this week, with less than a month until the November election. Widely seen as unflattering, the film will surely play along purely partisan lines. But it's worth noting that if not for the unpopular Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC), it may have had no chance of hitting theaters before the election.

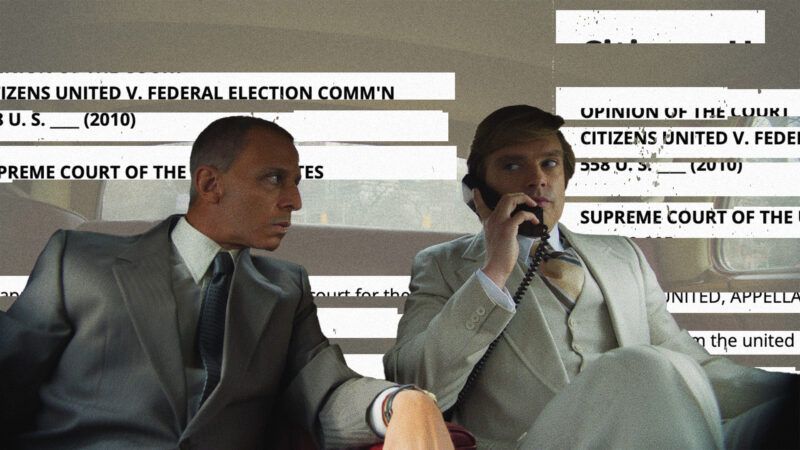

The Apprentice stars Sebastian Stan as a young Trump and Jeremy Strong (of HBO's Succession) as Roy Cohn, the infamous "fixer" who acted as Trump's personal attorney and mentor in the 1970s and 1980s. The film depicts Trump's evolution under Cohn's tutelage, from Queens real estate scion to Manhattan bullshit artist. (In the film's trailer, Cohn advises Trump to "admit nothing, deny everything," and "no matter what happens, you claim victory and never admit defeat.")

The film debuted to positive reviews at the Cannes Film Festival, though it took home no awards. But despite the warm reception, the film struggled to find distribution in the U.S. In May, Trump threatened a defamation suit over a scene that depicts him sexually assaulting his then-wife, Ivana. (She claimed in divorce proceedings that the assault took place but later recanted, calling the allegation "totally without merit" when he ran for president. Ivana Trump died in 2022.)

"This 'film' is pure malicious defamation, should never see the light of day, and doesn't even deserve a place in the straight-to-DVD section of a bargain bin at a soon-to-be-closed discount movie store, it belongs in a dumpster fire," Steven Cheung, communications director for Trump's reelection campaign, said in a statement.

"It makes sense that the Trump campaign wanted to block it," Semafor's David Weigel wrote after seeing a screener. "No voter on the fence will go MAGA after watching Sebastian Stan's Trump learn how to be a 'killer' from Cohn, or seeing a young Roger Stone get introduced as a specialist in 'dirty tricks.'" On the other hand, Johnny Oleksinski of the New York Post called the film "reasonably entertaining" and said it depicts "a mostly sympathetic portrayal" of Trump.

Still, it's no wonder that Trump and company would be miffed at the film's release right before the election. But if not for the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. FEC, they could have simply had the government ban the movie for them.

Citizens United has become a popular object of scorn, particularly on the left: Days after the decision, President Barack Obama singled it out for criticism at the 2010 State of the Union address, saying that "the Supreme Court reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests—including foreign corporations—to spend without limit in our elections." (In video of the speech, Justice Samuel Alito could be seen saying this was "not true.")

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D–R.I.) called it "one of the most disgraceful decisions by any Supreme Court." Keith Olbermann said on his MSNBC show that it "might actually have more dire implications than Dred Scott v. Sandford"—the execrable 1857 decision finding that African Americans, whether free or enslaved, had "no rights which the white man was bound to respect" and were thus not entitled to citizenship.

An Ipsos poll conducted in 2017, seven years after the decision, found that 30 percent of respondents somewhat or strongly support the court's conclusion, with 48 percent somewhat or strongly in opposition, and another 22 percent saying they "don't know."

But it's worth remembering what the Citizens United case was actually about.

Citizens United, a conservative advocacy group, released a film critical of Hillary Clinton in January 2008. Hillary: The Movie was intended to hurt Clinton in that year's Democratic presidential primary; it ran in theaters and was distributed on DVD, and the organization also hoped to both air the film on TV and run ads for it.

But that violated the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, often called the McCain-Feingold Act after its primary sponsors, then-Sens. John McCain (R–Ariz.) and Russ Feingold (D–Wis.). McCain-Feingold amended federal law to ban the use of corporate or union funding for any "electioneering communication," defined as "any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication" that "refers to a clearly identified candidate for Federal office" and is released within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election.

Citizens United sued the FEC, seeking a preliminary injunction so it would not be prevented from airing or advertising the film. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia declined to issue an injunction, finding the film "susceptible of no other interpretation than to inform the electorate that Senator Clinton is unfit for office, that the United States would be a dangerous place in a President Hillary Clinton world, and that viewers should vote against her." It determined that McCain-Feingold prevented Citizens United from paying to air the movie within 30 days of the Democratic primary—and potentially within 60 days of the general election.

(Ironically, Citizens United had filed an FEC complaint in 2004 seeking to prevent Michael Moore from releasing Fahrenheit 9/11, his documentary critical of President George W. Bush, ahead of that year's presidential election. "All we want is Michael Moore to follow the law," said Citizens United head David Bossie. "McCain-Feingold limits my free speech as well as Michael Moore's.")

In a January 2010 ruling, the Supreme Court overturned the provision of McCain-Feingold banning political spending by corporate collectives. "Limiting independent expenditures on political campaigns by groups such as corporations, labor unions, or other collective entities violates the First Amendment because limitations constitute a prior restraint on speech," found the 5–4 majority.

But there was more to the case than simply corporate donations. At oral arguments in March 2009, Alito asked Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart whether "there isn't any constitutional difference between the distribution of this movie on video [on] demand and providing access on the Internet, providing DVDs, either through a commercial service or maybe in a public library, providing the same thing in a book? Would the Constitution permit the restriction of all of those as well?"

"I think the Constitution would have permitted Congress to apply the electioneering communication restrictions," Stewart agreed. "Those could have been applied to

additional media as well."

"That's pretty incredible," Alito replied.

Over the course of the session, Stewart would further claim that the government "could prohibit the publication" of such a book—even if, as Chief Justice John Roberts asked hypothetically, "it's a 500-page book" and only contains "one use of the candidate's name." Stewart noted that a corporation would simply be forced to use "PAC funds"—referring to a separately funded political action committee—instead of corporate treasury funds, but as Alito noted, "most publishers are corporations" and would be ill-served by that distinction.

In the absence of Citizens United, then, the government's position was that it would be perfectly constitutional to prevent the publication or release—within two months of an election—of any book, film, TV show, pamphlet, etc., that mentions a candidate for office by name. That could certainly include the theatrical release of a biographical film that negatively portrays Donald Trump, the former president and current Republican nominee.

If you get to see The Apprentice in theaters before Election Day, then, you can thank Citizens United.

Show Comments (40)