Richard Nixon Privately Admitted Marijuana Was 'Not Particularly Dangerous'

The recordings demonstrate yet again that drug warriors always knew marijuana wasn't that bad—they just didn't care.

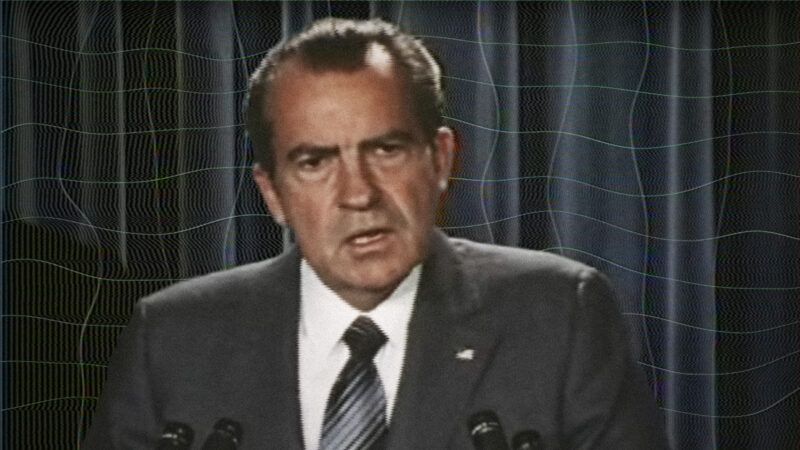

While America has long had restrictive drug laws, the "war on drugs" is considered to have begun in earnest in June 1971. "America's public enemy number one," President Richard Nixon proclaimed in a press conference, "is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive."

Recently discovered audio of Nixon's private conversations indicates that he may not have completely believed what he said.

During his presidency, Nixon infamously recorded thousands of hours of his conversations; the existence of recordings in which he discussed the Watergate break-in and cover-up proved key to his downfall. In recordings from 1972 and 1973, as reported by The New York Times, Nixon admitted to aides that perhaps marijuana wasn't as bad as he was publicly letting on.

"Let me say, I know nothing about marijuana," Nixon says in March 1973, in a grainy audio recording that is hard to hear at times. "I know that it's not particularly dangerous; I know most of the kids are for legalizing it."

"But on the other hand," he continues, "it's the wrong signal at this time."

In October 1970, Nixon had signed the Controlled Substances Act into law, which categorized marijuana as a Schedule I narcotic—the most severe classification, reserved for substances "with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse."

But in private, the president expressed misgivings about overly punitive sentences for marijuana. "The penalties are ridiculous," he told John Ehrlichman, his domestic policy advisor. "I have no problem with the fact that there should be, there should be an evaluation of penalties on it, and there should not be penalties that, you know, like in Texas where people get 10 years for marijuana. That's wrong. In other words, the penalties should be commensurate with the crime."

In another recording from September 1972, just weeks before Nixon would stand for reelection, White House Counsel Charles Colson spoke about Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern's support for decriminalization "and maybe reducing the penalties" for marijuana use. "Actually I'm for, I am for modification of penalties in many areas," Nixon noted, "but I don't talk about it anymore, exactly."

"Well sure, it's a responsible position to reduce some of the penalties," Colson replied.

This even-handed attitude was absent from Nixon's policy platform. In fact, in March 1970, LSD researcher Timothy Leary received a prison sentence of up to 10 years for possessing less than an ounce of marijuana. But instead of advocating "reducing the penalties," Nixon—who saw Leary as an enemy—did the opposite: "I want a goddamn strong statement on marijuana," he told Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman in May 1970. "By God we are going to hit the marijuana thing, and I want to hit it right square in the puss." Nixon declared war on drugs the following month.

Nixon's private acknowledgements, contrasted with his public pronouncements, are certainly infuriating. In 2020 alone, more than 317,000 people in the U.S. were arrested for marijuana possession—which actually represented a 36 percent decrease from the previous year. Black Americans represented nearly 39 percent of that total, despite accounting for less than 14 percent of the total population.

Not that any of this would likely have been news to the Nixon White House. When the Controlled Substances Act placed marijuana into the most severe category, Nixon formed the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse to study the issue. In 1972, the commission released its report, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, which among other things unanimously recommended decriminalizing the personal possession and use of marijuana, encouraging "persuasion rather than prosecution." Despite having picked nine of its 13 members, Nixon ignored the commission's findings.

Ehrlichman admitted the drug war's real motivations to journalist Dan Baum in 1994:

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I'm saying? We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

The new revelations that Nixon and his aides privately expressed uncertainty about the efficacy of criminalizing marijuana is maddening when considered in the context of how many people have been arrested and had their lives turned upside down simply for possession. But as the historical record shows, this information was freely available at the time; they just didn't care.

Show Comments (45)