A Federal Judge Rejects the Lame Excuses of Texas Cops Who Kidnapped a Supposedly 'Abandoned' Teenager

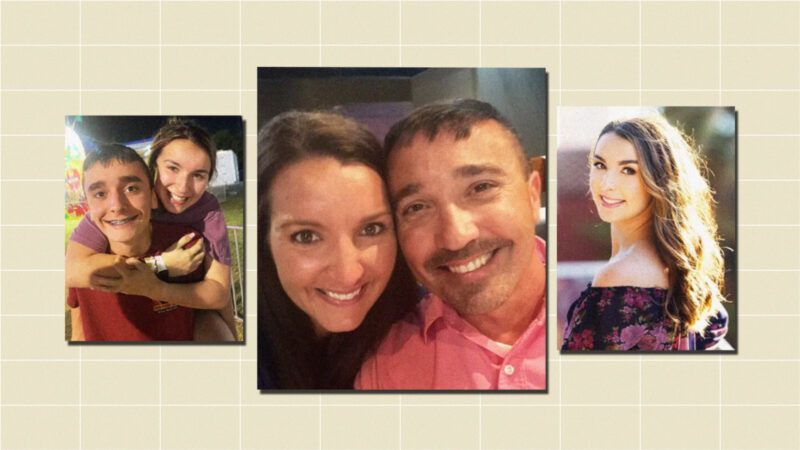

The decision clears the way for a jury to consider Megan and Adam McMurry's constitutional claims against the officers who snatched their daughter.

On a Friday morning in October 2018, two police officers who worked for a Texas school district kidnapped a 14-year-old girl from her home based on spurious child abandonment concerns. Although Texas Child Protective Services (CPS) promptly determined there was no reason to suspect neglect or abuse, the cops pursued criminal charges against the girl's mother, leading to a trial in which a jury acquitted her after deliberating for five minutes.

A civil rights lawsuit provoked by these outrageous abuses has been working its way through the federal courts for nearly four years. On Tuesday, a federal judge scathingly rejected the officers' motion for summary judgment, clearing the way for a trial.

"A lot of cops, like these two, think they can do whatever they want and search whatever they want and make up their own rules because they believe nobody will hold them accountable," Megan McMurry, the lead plaintiff in the case, says in an email. "It has been almost six years, but I want to change that narrative. Our system is broken. Our rights were violated and our lives have been constantly trampled through as we have fought to defend those rights."

The case began with a five-day trip to Kuwait that McMurry, then a special education teacher at Abell Junior High School in Midland, Texas, arranged so she could visit a school that had offered her a job. McMurry's husband, Adam, was a National Guard soldier who had been deployed to the Middle East. After learning that Adam had been assigned to another stint in Kuwait, Megan began considering a move there but wanted to check out the potential job in person before making a final decision.

Since the couple's children, Jade and Connor, were not keen on joining her, McMurry asked Vanessa Vallejos, a neighbor in the gated apartment complex where the family lived, to watch them. Vallejos and her husband, Gabe, knew the family well because Jade babysat their 6-year-old son.

Connor was 12 and attending Abell, the school where McMurry worked, while Jade, two years older, was homeschooled via online courses. On October 26, 2018, Abell's guidance counselor, who had agreed to bring Connor to school, was unable to do so because she was sick. So she texted Alexandra Weaver, a Midland Independent School District (MISD) police officer who lived in the neighborhood, asking if she could give Connor a ride. Although another Abell employee ended up bringing Connor to school, Weaver's involvement did not end there.

Weaver knew that McMurry was out of the country, since she had sent an email notifying all Abell employees of her trip. Concerned that Jade and Connor had been left alone without supervision, Weaver contacted her supervisor, MISD police officer Kevin Brunner. Weaver and Brunner conferred with three of McMurry's co-workers, who told them that Jade was homeschooled and that Vallejos was periodically checking on her and her brother. The officers nevertheless filed a CPS complaint and, instead of waiting for a response, decided to do a "welfare check" on Jade.

When Weaver and Brunner arrived at the McMurrys' apartment, Jade confirmed that Vallejos had been charged with looking after her and Connor, noting that she had come by that very morning. Jade said she could give the officers Vallejos' number if they wanted to check with her about the arrangement. Disregarding this information, Brunner told Jade to put on warmer clothing so she could leave the apartment. This happened less than a minute after Jade answered the door.

As Jade began to follow Brunner's instructions, body camera video showed, he asked her, "Do you mind if she [Weaver] comes in the house with you?" Jade's response was ambiguous: "Mm-hmm." Then she burst into tears, saying, "I'm scared." Taking that as an invitation, Weaver entered the apartment and began poking around. She inspected the living room and the kitchen, opening the pantry, the refrigerator, and the freezer. Her search found no evidence that Jade was in any danger.

Unfazed, Weaver and Brunner took Jade to the apartment complex's conference room, where they grilled her and refused to let her call her father in Kuwait. After questioning Jade for about 15 minutes, the officers drove her to Abell in their police car. At this point, Adam McMurry was trying to contact Jade, but Brunner told her not to answer. He also advised her against texting or calling her mother. On the way to Abell, Brunner notified CPS that he was bringing Jade there.

At the school, Brunner put Jade in a private office. Vallejos and her husband arrived and again confirmed that they were keeping an eye on Jade and Connor while their mother was out of the country. Brunner let Vallejos see Jade and contact Adam McMurry via FaceTime. By that afternoon, CPS had determined there was no basis to believe Jade and Connor had been abandoned and allowed them to return home with their neighbors.

Brunner still was not satisfied. Two months later, he filed two probable cause affidavits that accused Megan McMurry of abandoning or endangering her children. She spent 19 hours in jail before posting bail. During her four-day trial in January 2020, the jurors heard all the facts that Weaver and Brunner already knew when they decided to snatch Jade from her home. Vanessa and Gabe Vallejos testified. So did the CPS investigator, his supervisor, and Weaver. Brunner skipped the trial, saying it conflicted with his vacation plans. When Weaver was asked why Jade was not allowed to speak with her father, she preposterously claimed that "I didn't want to cause him any undue stress."

McMurry's prompt acquittal suggested that the jurors did not think Weaver and Brunner's avowed concern for Jade's welfare was reasonable. Nor did U.S. District Judge David Counts, who in September 2021 rejected the officers' motion to dismiss the lawsuit that Megan and Adam McMurry had filed in October 2020.

The McMurrys alleged that Weaver and Brunner had violated the Fourth Amendment by detaining Jade and by searching the apartment. They said the officers also had violated their 14th Amendment right to due process by taking Jade from her home. Weaver and Brunner claimed they were protected by qualified immunity, which shields government officials from liability unless their alleged misconduct violated "clearly established" law.

Counts disagreed. Brunner appealed that decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, which affirmed Counts' order in December 2022. "The facts here are particularly egregious," Judge Andrew Oldham noted in a concurring opinion. He elaborated:

Weaver performed an illegal search in front of her supervisor (Brunner). And instead of settling for one constitutional violation (the search), Brunner went on to commit two more (unlawfully seizing [Jade] and violating the McMurrys' due-process rights). And after taking custody of [Jade], Brunner prevented [her] from talking to her father and the Vallejos for a significant amount of time. All while [Jade] was crying and confused. Then CPS told Brunner that his safety concerns were baseless. And still, inexplicably, Brunner persisted and pushed for criminal charges against Mrs. McMurry. Like CPS, a jury of Mrs. McMurry's peers squarely rejected Brunner's charges. But the damage was already done: Mrs. McMurry was already fired, was already prevented from teaching again, and had already spent 19 hours in jail.

After that resounding defeat, Brunner unsuccessfully asked the 5th Circuit to reconsider the case and unsuccessfully sought Supreme Court review. Then Brunner and Weaver filed motions for summary judgment with the district court, reasserting their qualified immunity claims. Unsurprisingly, Counts was no more impressed by their arguments the second time around.

Regarding the claim that the officers' seizure of Jade violated her Fourth Amendment rights, Counts says, the relevant question is whether a reasonable person in her situation would have believed she could disregard the cops' instructions. "Of course not," he writes. "Although it goes unmentioned in Defendants' motions, the Fifth Circuit has already held in this case that [Jade] was unlawfully seized 'in violation of the Fourth Amendment as a reasonable fourteen-year-old would not have believed she was free to leave when an officer removed [her] from her home for questioning while instructing her not to respond to calls from her father.' Defendants' motions even confirm the facts underlying that holding. So no, this was not 'a consensual act of transportation'; [Jade] was unlawfully seized in violation of her Fourth Amendment rights."

Were those rights "clearly established"? As Counts notes, the 5th Circuit has already said they were "under these exact facts."

Weaver and Brunner argued that the McMurrays' due process claim was defeated by Jade's purported "consent." Leaving aside the absurdity of the argument that Jade voluntarily accompanied the officers, Counts notes, the relevant consent in this context is parental consent. Jade "was following her parents' instruction to continue her homeschooling in the family apartment during school hours," he writes. "Defendants then overruled that parental instruction by unlawfully removing [Jade] without a court order or exigent circumstances. Thus, Defendants 'obviously deprived the McMurrys of their liberty interest' in the care, custody, and management of their child."

The McMurrys "did not receive the process they were due," the 5th Circuit noted. "In fact, they received no process whatsoever. No ex parte court order, no warrant, no notice, no hearing. Nothing. Surely, the McMurrys had a right to at least some predeprivation process before their child was snatched from their home."

Weaver claimed her search of the apartment was justified by Jade's alleged consent. "The Court has reviewed the footage from Officer Weaver's body camera for the entire time she was in the family apartment," Counts writes, "and there is nothing that sounds or looks like [Jade] giving Officer Weaver consent to search anything in the apartment. So the Court assumes that Officer Weaver's belief is that [Jade's] consent to her entry also provided consent to search the apartment. But the idea that the scope of [Jade's] earlier 'consent' to entry can be construed as consenting to Officer Weaver's search is ridiculous….The Court finds it hard to believe that [Jade's] 'Mm-hmm,' followed by her bursting into tears and saying 'I'm scared' also gave Officer Weaver free rein to search the family apartment."

Weaver also argued that her search was authorized by a doctrine that allows warrantless searches when they serve a "special need" distinct from criminal law enforcement. That doctrine, Counts writes, "does [not] even apply in this context," since the search was plainly aimed at discovering evidence of child neglect or abuse, which is "not separate from general law enforcement." Furthermore, he says, Weaver had no reason to believe that Jade was in danger.

"Officer Weaver searched the family apartment without consent, probable cause, exigent circumstances, or any 'special need,'" Counts writes. "Accordingly, Officer Weaver's search violated the McMurrys' Fourth Amendment rights." And in case there is any doubt, he notes that "the right to be free from an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment was 'clearly established' at the time of Officer Weaver's search."

Counts' conclusion reflects his dismay at Weaver and Brunner's arguments. "The Court finds it distasteful to review these facts and then entertain the argument that Mrs. McMurry is responsible for 'separating the family,'" he writes. "Or that [Jade] was 'minimally inconvenienced' by her unlawful seizure. Or that taking a crying 14-year-old girl away from her home without exigent circumstances, all while telling her not to contact her parents, was a simple 'consensual act of transportation.'"

Because the McMurrys have overcome the obstacle of qualified immunity, they will finally have an opportunity to present their constitutional claims to a jury. A trial is scheduled for September 3. The defendants' lame excuses are unlikely to fare any better in that context.

"It means a lot for the judge to see the evidence, specifically the bodycam [showing] how these officers treated my daughter," McMurry says. "I can't wait for a jury of my peers to join me in holding the officers accountable for their actions."

Show Comments (34)